ALK+疾病:药物如何排兵布阵,突变亚型是否值得关注?

ALK+疾病:现状与挑战

在转移性非小细胞肺癌中,ALK+肿瘤在许多方面都是独一无二的,它们具有最低的基因复杂性,平均肿瘤突变负荷(tumor mutational burden,TMB)低于3 muts/Mbp[1,2],却需要目前最复杂的治疗策略,即需要肿瘤内科、肺介入科与放射科、胸外科、放射肿瘤学以及分子病理学数年的高水平专业知识及密切配合,以期给予患者最佳的治疗结局。即使仅接受一种TKI治疗的ALK+ NSCLC患者,其预后也优于接受TKI治疗的EGFR+ NSCLC患者,而序贯ALK TKI给药同时可获得5年以上的中位总生存期,这无疑是现代胸部肿瘤学的最大进展之一[1,3]。取得这一非凡成就的关键是药物的快速研发,现在已有5种且常规可及的ALK抑制剂,分别是克唑替尼、色瑞替尼、阿来替尼、布加替尼和劳拉替尼[4]。除了临床试验的设定之外,在快速更迭的监管批准框架内,这些药物的使用顺序复杂多变,并且在寡转移的情况下会辅以局部消融治疗[5]。在这个极具变化的领域中,目前有两个主要问题对接下来的发展具有重要意义:现有治疗手段的最佳应用策略,以及早期治疗失败的分子特征以指导新的治疗思路。

好药的先后之选

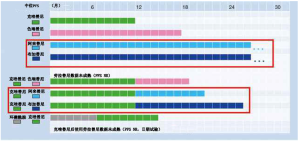

一种“好”药通常会兼顾药物的疗效与耐受性、安全性(图1A)。更进一步来说,评估药物疗效的最佳指标是一线治疗的无进展生存期(progression-free survival,PFS),因为这综合考量了初治背景下药物的缓解率及缓解持续时间。因此,在不同的药物中,“最佳药物”通常指一线PFS最长的药物(图1A)。如果这些“最佳药物”在二线使用时疗效降低,那么最好优先使用(“好药先用”,图1B),但如果它仍能保持疗效,那么最好延后使用(“好药后用”,图1B)。如果在“最佳药物”不会出现耐药的特殊情况下,我们甚至可能把它作为所有其他靶向药物失败后的最终选择(图1B)。

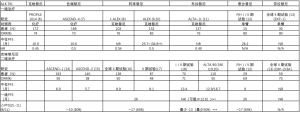

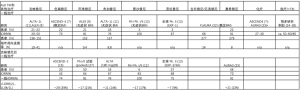

对于现在的ALK+疾病来说,什么才是“最佳”?显然,与一线ALK抑制剂克唑替尼相比,二代ALK抑制剂阿来替尼和布加替尼在一线治疗全身疗效方面具有显著优势,在与克唑替尼的头对头比较中,二者疗效相似,中位客观缓解率(objective response rates,ORR)约为80%,PFS风险比(hazard ratios,HR)约为0.5,中位PFS时间超过2年(表1)[8-9,11,21]。值得注意的是,随访时间较长的ALEX研究显示,阿来替尼的PFS曲线在50%左右趋于平缓,这使得中位一线PFS指标相对“不牢靠”[9-10],因此在这种背景下,突显出了PFS HR作为疗效测量指标的优越性。我们还应注意到,尽管阿来替尼具有整体优势,但在前6个月内,两组的PFS曲线趋势相似[9]。相比之下,其他下一代ALK TKI 要么一线PFS较短,例如ASCEND-4研究中色瑞替尼PFS仅为17个月[7],要么只有单臂、II期研究数据,例如恩沙替尼的26个月[12],劳拉替尼一线ORR有望达到90%,但PFS数据仍然不成熟(表1)[13]。相对于克唑替尼,阿来替尼和布加替尼的一线颅内疗效更佳,PFS HRs分别为0.4和0.27,每年颅内进展率低于10%(表2)[9,11]。由于具有良好的中枢神经系统(central nervous system,CNS)穿透性,所有下一代ALK TKI的颅内ORR非常高,约为80%,与全身ORR(表1)及放疗时的颅内ORR相似,远高于克唑替尼或化疗时的颅内ORR(表2)[6,22-26,29]。新型ALK抑制剂的颅内高疗效尤为重要,因为颅内转移会影响相当一部分ALK+ NSCLC患者,在初诊时约25%患者合并颅内转移,如果一线使用克唑替尼治疗,60%患者在3年后会出现颅内转移[30-31];并且由于这些患者更年轻、预期寿命更长,他们会因CNS受侵导致认知障碍、驾驶限制和生活质量下降而遭受更多的痛苦。

Full table

Full table

同时,如果在克唑替尼后使用下一代ALK抑制剂,会丧失50%的全身疗效,阿来替尼PFS会减少17个月[16,17,32],布加替尼(预计)PFS减少至少13个月[18-20,33],已经超过了一线应用克唑替尼整体的PFS时间(表1)。二线治疗颅内疗效也会下降,阿来替尼和布加替尼的颅内ORR约为65%(表2)[15,27-28,34],远低于一线治疗时的80%(表1)。更重要的是,由于接受克唑替尼的患者每年颅内进展率>20%,而接受阿来替尼及布加替尼的患者每年颅内进展率<10%(表2),约20%的患者接受一线克唑替尼治疗时出现颅内进展,并无接受第二代药物治疗的机会。因此,目前对于ALK+疾病“优选选择”阿来替尼或布加替尼的两个主要的论点为:(Ⅰ)一线使用阿来替尼或布加替尼的中位PFS优于一线克唑替尼序贯二线阿来替尼或布加替尼PFS的总和(表1, 图2);(Ⅱ)优先使用阿来替尼或布加替尼相比克唑替尼能显著延缓颅内进展,PFS HR<0.5,每年颅内进展率绝对值数值分别为<10%、>20%(表2)。因此,目前NCCN及ESMO指南都已承认阿来替尼是比克唑替尼更好的一线治疗选择,布加替尼的优先使用正在等待监管部门的批准[35-36]。

此外,还有一些额外、间接的支持“好药先用”的重要论据。首先,下一代ALK抑制剂研究之间的比较表明,“好药先用”可能会提高长期反应率。例如,在ALEX研究中,阿来替尼和克唑替尼的前6个月PFS曲线相似,但随后两者分离趋势增加[9-10]。此外,在2014年ASCEND-1研究分析中,先前未经治疗的患者接受色瑞替尼治疗的PFS曲线在50%左右趋于平缓,而先前经克唑替尼治疗的患者PFS曲线持续下降,尽管这两条曲线的中位PFS相差很小[37]。2016年同一研究的数据更新中也可以看到类似的差异[14],并且在比较一线或二线使用阿来替尼[9,17]或布加替尼[11,19]的研究中,PFS曲线差异也很明显。在所有病例中,相比在克唑替尼后使用,优先应用二代ALK抑制剂可使PFS曲线趋于平缓时的水平升高,并且这种曲线间差异比中位PFS曲线的差异更明显。有趣的是,与伊马替尼相比,在慢性粒细胞白血病(精准医学的模型疾病)中,优先给予第二代TKI有助于实现深度分子缓解,成功停药的比例更高[38]。诚然,即使是恶性程度较低的ALK+疾病,治疗NSCLC也肯定需要比单药TKI更多的手段[1],但是,第二代ALK抑制剂仍然是一个前景光明的联合治疗手段,不仅可联合局部治疗用于寡转移病例,也可实验性地用于根治其他广泛转移或残留病灶。

同样,一些数据表明,如果在TKI前进行化疗,也可降低疗效。在2014年PROFILE-1014研究的第一份报告[6]中,接受克唑替尼和化疗作为首次全身治疗的患者之间长期PFS(例如2年后PFS曲线的尾部)存在约20%的显著差异。而另一项研究表明[39],化疗后二线应用克唑替尼或化疗时,这种差异并不明显,尽管两项研究的PFS HRs非常相似(0.45 vs 0.49)。重要的是,2018年公布的PROFILE-1014研究的最终结果显示,尽管存在交叉,但上述20%左右的差异也反映在两组患者的5年OS中,即从长期来看,克唑替尼一线的患者疗效优于要比一线化疗二线序贯克唑替尼的患者[40]。这种化疗后TKI疗效降低的作用机制可能是由于细胞毒性药物的基因毒性作用[41],这种基因异常化的累积是TKI治疗失败的关键[42-44],而且由于ALK+疾病的基线TMB极低[1],这种异常化的累积的危害可能更大。基于这些考虑,先用化疗可能降低其他TKI的疗效,包括目前的“最佳药物”阿来替尼和布加替尼,尽管这些药物不会开展一线与化疗头对头比较的试验。对临床实践的具体启示为:(Ⅰ)对于转移性NSCLC,一般应等待包括ALK状态在内的分子检测结果,而不是“盲目”地启动化疗;(Ⅱ)在使用细胞毒性药物之前,一般应试过所有可能的TKI治疗方案;(Ⅲ)尚未获批准的ALK抑制剂在理想情况下应可用于同情用药情况。

关于放疗和“好药先用”药物的关系是怎样呢?Magnuson等在2017年发表的关于EGFR+NSCLC脑转移患者的回顾性研究中,除一线TKI外,还强烈主张行脑部放疗,但从目前来看,证据却恰恰相反[45]。在这项研究中,与TKI单独治疗相比,TKI联合立体定向(stereotactic,SRT)或全脑放疗(whole brain radiotherapy,WBRT)治疗患者的颅内进展率略高,并转化为显著的OS获益。然而,三组患者(使用第一/二代EGFR抑制剂,联合/不联合SRT/WBRT)的每年颅内进展率>20%,与FLAURA研究中采取相似治疗的对照组数据相当,显著高于口服奥希替尼的实验组<10%的每年颅内进展率[22]。换句话说,跨研究比较表明,奥希替尼抑制颅内进展的保护作用显著优于放疗,因此,放疗应作为奥希替尼治疗失败时的挽救性治疗手段(表2)。优先使用阿来替尼或布加替尼每年颅内进展率亦小于10%(表1)[9,11],这表明即使患者存在无症状和/或稳定的脑转移(表2),接受“好药先用”药物的ALK+患者也可能实现一线“去放疗化”。有趣的是,最近研究表明,对于>1 cm或有症状的颅内病灶亦然:即使这些病例已被排除在TKI研究外,常规使用阿来替尼治疗与临床研究疗效相当[46]。然而颅内寡转移患者是一个例外,应参照颅外寡转移患者的标准予以联合放疗[47]。在其他患者中,首选磁共振监测似乎更可取,SRT可作为颅内进展时的挽救手段,因为二线使用下一代ALK抑制剂疗效显著降低,类似于一线厄洛替尼/吉非替尼的疗效(表2),在Magnuson等人的研究中,补充SRT可以提高生存率[45]。我们还应关注SRT可治疗多达10个颅内病灶[48],而WBRT具有严重的神经认知后遗症[49],只要仍有潜在的靶向治疗手段,应尽量避免使用后者治疗ALK+ NSCLC。与此相反,阿来替尼与布加替尼的耐受性较好,3级不良反应发生率低,只有个位数,停药率大约10%,与克唑替尼相似[9,11]。甚至一线使用布加替尼的“早发性肺相关不良反应”发生率也显著低于二线应用(3% vs 9%)。

关于“好药先用”的第一个要点是,ALEX和ALTA-1L研究的OS数据仍不成熟[10,11],尚未证明其优于克唑替尼。但并不是推迟其应用的理由:考虑到如今ALK+ NSCLC患者的长期生存,“好药先用”的OS优势需要几年的时间才能显现。此外,PROFILE-1014研究的最终分析表明,即使在疗效明显增加的情况下,交叉入组也会掩盖OS的优势,例如克唑替尼对比化疗[40]。另一个值得注意的要点是,需遵循“好药先用”的后线治疗方案。小样本量研究表明,其他二代ALK抑制剂如色瑞替尼(n=20)和布加替尼(n=18例可评估疗效)在阿来替尼(50,51)后使用的疗效有限。然而对于布加替尼,体外和体内数据显示其对ALK耐药突变(包括G1202R)具有良好的活性[52],急需等待正在进行的大型国际II期研究(NCT03535740,n=103)提供明确结论。另外,在全球范围的II期试验中,二代ALK抑制剂治疗失败后,三代药物劳拉替尼仍显示出相当好的疗效,在未经选择人群中缓解率有40%~50%,对于约50%可检测到ALK耐药突变的患者,缓解率超过60%[13,53]。后者代表ALK TKI获得性耐药最常见的机制,常需要不同更强效的ALK抑制剂治疗,具体药物选择应由当前的特异性突变决定[5,43]。因此,检测ALK耐药突变的方法作为指导ALK+ NSCLC用药的工具正迅速变得重要[54,55]。目前可用的平台通常基于疾病进展时通过组织或液体二次活检(ctDNA)取得的DNA对ALK激酶结构域外显子进行下一代测序(next-generation sequencing,NGS)[56,57]。有趣的是,临床病理相关性表明,ALK耐药突变的特异性不仅受TKI测序影响[58],还受ALK突变亚型影响[59],因此晚期ALK+疾病的治疗选择与ALK突变亚型相关。然而,ALK融合突变亚型的临床意义要广泛得多,因此值得在下一节进行深入讨论。

突变亚型是否值得关注?

ALK+ NSCLC的诊断通常基于免疫组化检测ALK过表达或荧光原位杂交检测ALK易位,这在所有病例中都是常见的,同样可以预测ALK TKI的疗效[60-62]。但实际的分子改变,即ALK融合本身会因人而异,约90%的病例中涉及棘皮动物微管相关蛋白样4(echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like-4,EML4)作为伴侣基因[63]。在EML4-ALK+ NSCLC中也存在变异:30%~40%的病例具有较短的EML4-ALK变体3(V3, E6;A20),而V1(E13;A20)和V2(E20;A20)分别出现在40%和10%的病例中[63]。在常规的临床标本中,ALK融合突变亚型可以通过RT-PCR或NGS进行分型[64],但目前世界上仅有几家中心在开展。

如前所述,这些差异影响ALK耐药突变的发生,与V1亚型相比,V3亚型驱动的肿瘤更易发生耐药突变(约65% vs 45%)[59]。然而,重要的是要认识到V3亚型驱动肿瘤在其天然“野生型”状态下也对ALK抑制剂具有相对耐药性。体外研究表明,与V1-和V2-转染的细胞相比,第一代和第二代ALK抑制剂治疗V3-转染细胞的IC50增加,这可能是由于V3癌蛋白的稳定性更高,导致更广泛的聚集和更强的ALK磷酸化[65-67]。此外,V3通过招募NEK9和NEK7激酶促进微管稳定,增强细胞迁移和转移潜能[68]。这些特点与V3的特殊结构直接相关,V3是一个较短的变异体,缺乏V1和V2变异体具有的截短的EML4β-螺旋桨结构域,该结构域可降低稳定性并限制与细胞骨架的相互作用[67]。

ALK突变亚型的生物学差异带来了一些临床意义。首先,如果ALK TKI的IC50随ALK融合突变亚型的不同而变化,那么ALK耐药突变的IC50就不仅仅取决于耐药突变本身,还取决于耐药突变发生的源头——ALK融合突变亚型。大多数ALK突变“耐药谱”是在V1背景下产生的[43],与ALK耐药突变主要(超过2/3的病例)发生在V3背景下[59]的事实不符,而且V3本身对ALK抑制剂的IC50高于V1[65]。其次,对于基于V3背景的耐药谱,重要的是解决较短的V3a剪接突变亚型,而非V3b。V3a具有更高的致癌潜力[65-66],V3b在体外表现与V1相似[66,69]。

更重要的是ALK融合突变亚型对患者预后的影响,这是近期几项回顾性研究的主旨。ALK TKI治疗后V1突变患者较其他突变患者的PFS延长[70],V2突变患者较其他突变患者的PFS延长[71]。根据RECIST标准,V3突变患者较V1及V2突变患者的PFS缩短[64-65,68,72]。随访时间延长后,V3突变患者较V1和V2突变患者的至下次治疗时间[64]及OS均缩短[64,68,72]。同时,V3突变相关风险似乎在诊断时(开始某种特定治疗前)即存在[73]。新诊断的V3驱动肿瘤转移频率更高[74],IV期肿瘤转移部位更多[64],这与V3阳性肿瘤细胞具有更强的ALK表达及迁移能力相一致[68,74]。回顾性分析亦显示一致数据,V3状态不仅与三线治疗中双TKI耐药患者的预后相关[59],且与一线TKI和其他治疗(化疗、脑部放疗)的预后相关[64]。值得注意的是,有限的回顾性数据表明,其他“短”EML4-ALK变异,如V5(E2;A20)[65]和非EML4-ALK融合[75]也与较差的预后有关,而较长的EML4-ALK V2(E20;A20)似乎有利于预后[71]。

然而,目前该领域的一个主要问题是缺乏前瞻性数据,因为ALK融合变异的分型尚未纳入任何临床试验中。最近,一项利用事后验证ALK融合变异信息并试图补充ALEX研究的努力证明了其困难和局限性:应用FoundationOne对组织样本进行分型的成功率略高于1/3[76]。总体而言,以上数据表明,在三种主要的EML4-ALK变异V1、V2、V3中,与克唑替尼相比,应用阿来替尼的预后更好。但在非V1病例中,阿来替尼获益的趋势,即缓解率(P=0.103)和PFS(P=0.114)可能更低。这些数据仍然不成熟(基于2017年12月的截止数据),因为参与比较的组间患者较少(n=8-25,少于既往回顾性分析),且组间患者的其他临床和分子参数未能得到很好的平衡,解读这些数据必须谨慎。然而,研究中提出一个重要的可能性,即ALK突变亚型可能会影响“最佳药物”的选择及“好药先用”的用药顺序。该分析的更新结果,以及在ALTA-1L试验中优先使用布加替尼进行类似分析的结果都值得密切关注。

最近,TP53突变也被认为是ALK+ NSCLC中早期TKI失败和OS缩短的另一个的独立分子危险因素[71-72,77-78]。此外,在TP53阴性患者疾病进展时,约20%的患者的组织或液体二次活检中存在TP53突变,预后较差,与初始TP53突变肿瘤的预后相似[79]。ALK融合突变亚型和TP53突变对ALK+ NSCLC患者临床发展过程具有独立和潜在的协同作用,意味着在仅考虑其中一种因素的研究中,有大量的生物和临床变异性。为指导基于肿瘤分子特征的患者管理,需要对两者进行分型(可能还需要进一步评估仍未识别的分子特征),例如可以通过联合靶向RNA和DNA的NGS实现[80]。

高危V3+、TP53突变,特别是V3+TP53突变“双阳性”ALK+ NSCLC患者的最佳治疗管理目前尚未明确[1]。在讨论预后时,尤其对于V3+TP53突变的病例,需要有所保留,大多数患者可能尚未达到5年的生存时间[72]。此外,在疾病进展应考虑更积极的局部消融治疗,否则一些高危患者可能在几个月内所有ALK TKI治疗均失败,最后几年生存期内以姑息性化疗告终[72]。更频繁的影像学随访、额外的ctDNA监测[79]、更强效的ALK抑制剂的优先使用以及与实验性药物(如TP53靶向药物)的联合应用[81]都可能带来获益,但需要在前瞻性临床研究中进行验证。

结论

目前,ALK+ NSCLC是胸部肿瘤“精准医学”的先行者,也是研发新治疗方法的模型疾病。根据目前的数据,采用第二代ALK抑制剂(特别是阿来替尼和布加替尼)进行“好药先用”治疗,可显著延迟全身和颅内进展,避免早期放疗,并有望增加长期反应率。此外,确定EML4-ALK融合V3亚型和TP53突变是独立且可能协同的分子危险因素,有助于筛选病例进行更积极的治疗管理,并指导建立临床前模型以推进治疗方案的进展。ALK+疾病的共同特点是基因复杂性较低,不仅使临床预后相对较好,且使得研究个体分子特征影响更加容易。随着对ALK+疾病中关键分子参数的认识不断加深,更多可及的有效药物的增加,我们的理念也在持续更新,治疗储备也在不断增加。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor Nir Peled for the series dedicated to the Congress on Clinical Controversies in Lung Cancer (CCLC 2018) published in Precision Cancer Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/pcm.2019.05.01). The series dedicated to the Congress on Clinical Controversies in Lung Cancer (CCLC 2018) was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The author reports advisory board and lecture fees from Novartis, Roche, Chugai and Boehringer Ingelheim, as well as research funding from Novartis, Roche, AstraZeneca and Takeda. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Christopoulos P, Budczies J, Kirchner M, et al. Defining molecular risk in ALK+ NSCLC. Oncotarget 2019;10:3093-103. [Crossref]

- Spigel DR, Schrock AB, Fabrizio D, et al. Total mutation burden (TMB) in lung cancer (LC) and relationship with response to PD-1/PD-L1 targeted therapies. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:9017. [Crossref]

- Duruisseaux M, Besse B, Cadranel J, et al. Overall survival with crizotinib and next-generation ALK inhibitors in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (IFCT-1302 CLINALK): a French nationwide cohort retrospective study. Oncotarget 2017;8:21903-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golding B, Luu A, Jones R, et al. The function and therapeutic targeting of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Mol Cancer 2018;17:52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin JJ, Riely GJ, Shaw AT. Targeting ALK: Precision Medicine Takes on Drug Resistance. Cancer Discov 2017;7:137-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2167-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soria JC, Tan DSW, Chiari R, et al. First-line ceritinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (ASCEND-4): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2017;389:917-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hida T, Nokihara H, Kondo M, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (J-ALEX): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;390:29-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, et al. Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:829-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Camidge DR, Peters S, Mok T, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from the global phase III ALEX study of alectinib (ALC) vs crizotinib (CZ) in untreated advanced ALK+ NSCLC. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:abstr 9043.

- Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, et al. Brigatinib versus Crizotinib in ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2027-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horn L, Infante JR, Reckamp KL, et al. Ensartinib (X-396) in ALK-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Results from a First-in-Human Phase I/II, Multicenter Study. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:2771-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, et al. Lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1654-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim DW, Mehra R, Tan DSW, et al. Activity and safety of ceritinib in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (ASCEND-1): updated results from the multicentre, open-label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:452-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crinò L, Ahn MJ, De Marinis F, et al. Multicenter Phase II Study of Whole-Body and Intracranial Activity With Ceritinib in Patients With ALK-Rearranged Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Previously Treated With Chemotherapy and Crizotinib: Results From ASCEND-2. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2866-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ou SHI, Ahn JS, Petris LD, et al. Alectinib in Crizotinib-Refractory ALK-Rearranged Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase II Global Study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:661-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw AT, Gandhi L, Gadgeel S, et al. Alectinib in ALK-positive, crizotinib-resistant, non-small-cell lung cancer: a single-group, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:234-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gettinger SN, Bazhenova LA, Langer CJ, et al. Activity and safety of brigatinib in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer and other malignancies: a single-arm, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1683-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim DW, Tiseo M, Ahn MJ, et al. Brigatinib in Patients With Crizotinib-Refractory Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Randomized, Multicenter Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2490-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn M, Camidge DR, Tiseo M, et al. OA 05.05 Brigatinib in Crizotinib-Refractory ALK+ NSCLC: Updated Efficacy and Safety Results From ALTA, a Randomized Phase 2 Trial. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:S1755-6. [Crossref]

- Brosseau S, Gounant V, Zalcman G. (J)ALEX the great: a new era in the world of ALK inhibitors. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:S2138-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reungwetwattana T, Nakagawa K, Cho BC, et al. CNS Response to Osimertinib Versus Standard Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Patients With Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;JCO2018783118. [PubMed]

- Wu YL, Ahn MJ, Garassino MC, et al. CNS Efficacy of Osimertinib in Patients With T790M-Positive Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Data From a Randomized Phase III Trial (AURA3). J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2702-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Welsh JW, Komaki R, Amini A, et al. Phase II trial of erlotinib plus concurrent whole-brain radiation therapy for patients with brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:895-902. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsiao SH, Lin HC, Chou YT, et al. Impact of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations on intracranial treatment response and survival after brain metastases in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Lung Cancer 2013;81:455-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiang T, Min W, Li Y, et al. Radiotherapy plus EGFR TKIs in non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases: an update meta-analysis. Cancer Med 2016;5:1055-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gadgeel SM, Shaw AT, Govindan R, et al. Pooled Analysis of CNS Response to Alectinib in Two Studies of Pretreated Patients With ALK-Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:4079-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Camidge DR, Kim DW, Tiseo M, et al. Exploratory Analysis of Brigatinib Activity in Patients With Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Brain Metastases in Two Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2693-701. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshida T, Oya Y, Tanaka K, et al. Clinical impact of crizotinib on central nervous system progression in ALK-positive non-small lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2016;97:43-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doebele RC, Lu X, Sumey C, et al. Oncogene status predicts patterns of metastatic spread in treatment-naive nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 2012;118:4502-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rangachari D, Yamaguchi N, VanderLaan PA, et al. Brain metastases in patients with EGFR-mutated or ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancers. Lung Cancer 2015;88:108-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mezquita L, Besse B. Sequencing ALK inhibitors: alectinib in crizotinib-resistant patients, a phase 2 trial by Shaw et al. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:2997-3002. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sullivan I, Planchard D. Editorial on the article entitled "brigatinib efficacy and safety in patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive non-small cell lung cancer in a phase I/II trial". J Thorac Dis 2016;8:E1287-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayashi H, Nakagawa K. Current evidence in support of the second-generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) tyrosine kinase inhibitor alectinib for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer positive for ALK translocation. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:E1311-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Non-small cell lung cancer, version 2. 2019.

- Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2018;29:iv192-iv237. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw AT, Kim DW, Mehra R, et al. Ceritinib in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1189-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cortes JE. A second-generation TKI should always be used as initial therapy for CML. Blood Adv 2018;2:3653-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2385-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon BJ, Kim DW, Wu YL, et al. Final Overall Survival Analysis From a Study Comparing First-Line Crizotinib Versus Chemotherapy in ALK-Mutation-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2251-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheung-Ong K, Giaever G, Nislow C. DNA-damaging agents in cancer chemotherapy: serendipity and chemical biology. Chem Biol 2013;20:648-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sotillo R, Schvartzman JM, Socci ND, et al. Mad2-induced chromosome instability leads to lung tumour relapse after oncogene withdrawal. Nature 2010;464:436-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance to First- and Second-Generation ALK Inhibitors in ALK-Rearranged Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 2016;6:1118-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Westover D, Zugazagoitia J, Cho BC, et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to first- and second-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Ann Oncol 2018;29:i10-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Magnuson WJ, Lester-Coll NH, Wu AJ, et al. Management of Brain Metastases in Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor-Naïve Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Multi-Institutional Analysis. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1070-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin JJ, Jiang GY, Joshipura N, et al. Efficacy of Alectinib in Patients with ALK-Positive NSCLC and Symptomatic or Large CNS Metastases. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:683-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stephens SJ, Moravan MJ, Salama JK. Managing Patients With Oligometastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Oncol Pract 2018;14:23-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto M, Serizawa T, Shuto T, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with multiple brain metastases (JLGK0901): a multi-institutional prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:387-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tallet AV, Azria D, Barlesi F, et al. Neurocognitive function impairment after whole brain radiotherapy for brain metastases: actual assessment. Radiat Oncol 2012;7:77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hida T, Seto T, Horinouchi H, et al. Phase II study of ceritinib in alectinib-pretreated patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-rearranged metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer in Japan: ASCEND-9. Cancer Sci 2018;109:2863-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin JJ, Zhu VW, Schoenfeld AJ, et al. Brigatinib in Patients With Alectinib-Refractory ALK-Positive NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:1530-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang S, Anjum R, Squillace R, et al. The Potent ALK Inhibitor Brigatinib (AP26113) Overcomes Mechanisms of Resistance to First- and Second-Generation ALK Inhibitors in Preclinical Models. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:5527-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Besse B, et al. ALK Resistance Mutations and Efficacy of Lorlatinib in Advanced Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019;JCO1802236. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCoach CE, Blakely CM, Banks KC, et al. Clinical Utility of Cell-Free DNA for the Detection of ALK Fusions and Genomic Mechanisms of ALK Inhibitor Resistance in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:2758-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dagogo-Jack I, Brannon AR, Ferris LA, et al. Tracking the Evolution of Resistance to ALK Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors through Longitudinal Analysis of Circulating Tumor DNA. JCO Precis Oncol 2018;2018.

- Chen Y, Guo W, Fan J, et al. The applications of liquid biopsy in resistance surveillance of anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitor. Cancer Manag Res 2017;9:801-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Volckmar AL, Sultmann H, Riediger A, et al. A field guide for cancer diagnostics using cell-free DNA: From principles to practice and clinical applications. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2018;57:123-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoda S, Lin JJ, Lawrence MS, et al. Sequential ALK Inhibitors Can Select for Lorlatinib-Resistant Compound ALK Mutations in ALK-Positive Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 2018;8:714-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin JJ, Zhu VW, Yoda S, et al. Impact of EML4-ALK Variant on Resistance Mechanisms and Clinical Outcomes in ALK-Positive Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1199-206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalemkerian GP, Narula N, Kennedy EB, et al. Molecular Testing Guideline for the Selection of Patients With Lung Cancer for Treatment With Targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: American Society of Clinical Oncology Endorsement of the College of American Pathologists/International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/Association for Molecular Pathology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:911-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blackhall FH, Peters S, Bubendorf L, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcomes for patients with ALK-positive resected stage I to III adenocarcinoma: results from the European Thoracic Oncology Platform Lungscape Project. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2780-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gelsomino F, Rossi G, Tiseo M. Clinical implications and future perspectives in testing non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangements. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:220-3. [PubMed]

- Sabir SR, Yeoh S, Jackson G, et al. EML4-ALK Variants: Biological and Molecular Properties, and the Implications for Patients. Cancers (Basel) 2017;9:118. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christopoulos P, Endris V, Bozorgmehr F, et al. EML4-ALK fusion variant V3 is a high-risk feature conferring accelerated metastatic spread, early treatment failure and worse overall survival in ALK+ NSCLC. Int J Cancer 2018;142:2589-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woo CG, Seo S, Kim SW, et al. Differential protein stability and clinical responses of EML4-ALK fusion variants to various ALK inhibitors in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2017;28:791-7. [PubMed]

- Heuckmann JM, Balke-Want H, Malchers F, et al. Differential protein stability and ALK inhibitor sensitivity of EML4-ALK fusion variants. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:4682-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Richards MW, Law EW, Rennalls LP, et al. Crystal structure of EML1 reveals the basis for Hsp90 dependence of oncogenic EML4-ALK by disruption of an atypical beta-propeller domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:5195-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O’Regan L, Barone G, Adib R, et al. EML4-ALK V3 drives cell migration through NEK9 and NEK7 kinases in non-small-cell lung cancer. bioRxiv 2019;567305.

- Childress MA, Himmelberg SM, Chen H, et al. ALK Fusion Partners Impact Response to ALK Inhibition: Differential Effects on Sensitivity, Cellular Phenotypes, and Biochemical Properties. Mol Cancer Res 2018;16:1724-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshida T, Oya Y, Tanaka K, et al. Differential Crizotinib Response Duration Among ALK Fusion Variants in ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3383-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Zhang T, Zhang J, et al. Response to crizotinib in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancers with different ALK-fusion variants. Lung Cancer 2018;118:128-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christopoulos P, Kirchner M, Bozorgmehr F, et al. Identification of a highly lethal V3+TP53+ subset in ALK+ lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer 2019;144:190-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christopoulos P, Kirchner M, Endris V, et al. EML4-ALK V3, treatment resistance, and survival: refining the diagnosis of ALK+ NSCLC. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:S1989-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noh KW, Lee MS, Lee SE, et al. Molecular breakdown: a comprehensive view of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. J Pathol 2017;243:307-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum JN, Bloom R, Forys JT, et al. Genomic heterogeneity of ALK fusion breakpoints in non-small-cell lung cancer. Mod Pathol 2018;31:791-808. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Camidge DR, Dziadziuszko R, Peters S, et al. Updated Efficacy and Safety Data and Impact of the EML4-ALK Fusion Variant on the Efficacy of Alectinib in Untreated ALK-positive Advanced Non-small-cell Lung Cancer in the Global Phase III ALEX Study. J Thorac Oncol 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kron A, Alidousty C, Scheffler M, et al. Impact of TP53 mutation status on systemic treatment outcome in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2018;29:2068-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang WX, Xu CW, Chen YP, et al. TP53 mutations predict for poor survival in ALK rearrangement lung adenocarcinoma patients treated with crizotinib. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:2991-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christopoulos P, Dietz S, Kirchner M, et al. Detection of TP53 Mutations in Tissue or Liquid Rebiopsies at Progression Identifies ALK+ Lung Cancer Patients with Poor Survival. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11. [PubMed]

- Volckmar AL, Leichsenring J, Kirchner M, et al. Combined targeted DNA and RNA sequencing of advanced NSCLC in routine molecular diagnostics: Analysis of the first 3,000 Heidelberg cases. Int J Cancer 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bykov VJN, Eriksson SE, Bianchi J, et al. Targeting mutant p53 for efficient cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2018;18:89-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Christopoulos P. ALK disease: best first or later, and do we care about variants? Precis Cancer Med 2019;2:16.