BRAF非V600E突变的转移性非小细胞肺癌治疗的叙述性综述

介绍

肺癌仍然是全球癌症相关死亡的主要原因。在美国,肺癌占所有死亡病例的四分之一[1]。在过去十年中,随着精准医疗的出现,非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)异质性分子结构的确定、靶向治疗的发展彻底改变了治疗模式[2]。对于腺癌(ADC)亚型转移性非小细胞肺癌患者,进行分子检测以筛选可操作的驱动突变,如表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)和间变性淋巴瘤酶突变,以及Kirsten大鼠肉瘤病毒癌基因(KRAS)和受体酪氨酸激酶(ROS1)易位。美国食品药品监督管理局(FDA)批准的有效靶向治疗显著延长了携带这些改变的患者的预期寿命。我们根据叙述性审查报告核对表(在线获取:https:// pcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pcm-21-49/rc)呈现以下文章。

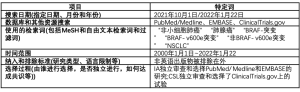

方法

我们使用术语“非小细胞肺癌”“肺腺癌”“BRAF突变”“BRAF-V600E突变”“非BRAF-V600E突变”“NSCLC”在EMBASE和MEDLINE/PubMed中搜索直至2021年10月的英语文献。所有搜索都是在2021年8月至10月进行的。

该检索由第一作者I.A.独立进行。非英语出版物被排除在外。

我们在ClinicalTrials.gov搜索了涉及BRAF突变患者的活跃试验列表。该检索由第二作者C.L.独立进行。表1列出了进一步的系统程序。

Full table

非小细胞肺癌的BRAF突变

V-raf鼠肉瘤病毒癌基因同源物B1(BRAF)原癌基因属于丝氨酸-苏氨酸激酶类,在丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(MAPK)通路中发挥重要作用[3]。位于7号染色体上的致癌性BRAF突变已在多种癌症中检测到,包括黑色素瘤、结肠直肠癌、肺癌和甲状腺乳头状癌。长期以来,已知这些突变预示着各种肿瘤类型的预后较差。在一项系统综述中[4],BRAF突变使结直肠癌患者的死亡率风险增加2.25倍,HR=2.25(95%CI:1.82~2.83),使黑色素瘤患者的死亡率风险增加1.7倍(95%CI:1.37~2.12)。由于其在NSCLC患者中的发生率较低,因此对其临床特征和预后意义的定义较少,且文献中的结果相互矛盾。

大约2%~4%的非小细胞肺癌患者发生BRAF突变[5,6]。根据所采用的检测方法,报告的发病率存在差异。免疫组织化学(IHC)可以筛查BRAF V600E突变,但受限于肿瘤细胞异质性和可用组织数量有限。Sanger测序是精确肿瘤学的金标准,但因其只能识别频率为15%~20%的变化的能力而受到限制。与基于PCR的Sanger测序相比,组织下一代测序(NGS)技术具有较高的灵敏度和可接受的特异性。基于血浆细胞游离DNA的NGS因其快速性和成本效益而成为新兴工具[7]。Marchetti等人的一项回顾性系列研究[8]评估了1 046例非小细胞肺癌患者中BRAF突变的存在,其中739例为腺癌,307例为鳞状细胞癌(SCC),并注意到在3.5%的肿瘤和4.9%的肺腺癌中存在这些基因组改变。

BRAF突变通常与其他驱动突变不同。它们通常被分为三类:1类突变信号为RAS非依赖性活性单体(如V600E);2类突变是组成型活性的RAS-非依赖性二聚体;3类突变的激酶活性较低或缺失[9]。最常见的BRAF突变涉及密码子600处谷氨酸取代缬氨酸(V600E),约占BRAF突变的55%。在Marchetti等人的研究中,ADCs中V600E突变的发生率为2.8%[8]。他们发现这种情况在女性中更为普遍(在患有ADC的女性中约为9%),但与吸烟史无关。具有这种突变的肿瘤侵袭性更强、预后较差。

在非小细胞肺癌中,45%的BRAF突变是非V600E突变,是报告的许多突变之一,如G469A(35%)或D594G(10%)[10]。与V600E相比,非V600E突变主要发现于吸烟者的早期阶段,似乎没有预后意义。

虽然BRAF V600E的致病作用及其在包括非小细胞肺癌在内的许多癌症中的靶向性已经明确确立,但更罕见的非V600E突变在癌症中的作用仍在评估中,并且正在临床前和临床试验环境中对携带这些突变的肿瘤进行新疗法的试验。一项估计表明,具有非V600 BRAF突变的肺癌每年导致全球约4万人死亡[11]。

靶向BRAF突变

BRAF基因编码丝氨酸/苏氨酸蛋白激酶,是细胞生长和增殖的关键调节因子。酶激酶结构域或p-loop位于B-Raf蛋白的457~717氨基酸残基内。残基596~600是激酶结构域内的一个部分,它与磷酸盐结合环相互作用,使激酶处于锁定位置。该激活环磷酸化后,促分裂原活化的2激酶1和2(MAP2K 1/2)信号通路被触发,进而激活其他蛋白,最终导致细胞增殖。L597和V600残基与激酶结构域内的其他氨基酸特异性相互作用,使其保持非活性,直至被磷酸化。

在Tissot等人的研究中,BRAF V600E突变型非小细胞肺癌患者的中位总生存期(OS)长于BRAF非V600E突变型非小细胞肺癌患者(分别为25个月和13个月,P=0.153)[12]。Ⅳ期V600E突变患者的OS也比非V600E患者长,但无统计学意义(16个月VS. 7个月,P=0.272)。值得注意的是,在该研究人群中,在携带BRAF非V600E突变的38例患者中,有5例患者同时存在KRAS突变。这与BRAF-V600E突变形成对比,后者与所有其他驱动突变相互排斥。据推测,这将导致对靶向治疗(如达巴非尼)的耐药性,因为在这种情况下,BRAF抑制会激活RAS的反馈回路[13,14]。

对于伴有BRAF V600E突变的转移性非小细胞肺癌,首选靶向治疗作为一线全身治疗方案,即联合使用达布芬尼(RAF-抑制剂)和曲马替尼(MEK-抑制剂)。基于Ⅱ期研究NCT01336634,针对既往接受过治疗的患者[3]和未接受过治疗的患者[4],FDA于2015年10月批准将这些药物指定为治疗该特定患者分组的罕用药。随后,FDA在2017年定期批准达布芬尼和曲马替尼联合治疗伴BRAF V600E突变的转移性非小细胞肺癌[15,16]。对于PD-L1>50%的患者,免疫治疗、靶向治疗或免疫治疗与化疗联合治疗都是FDA批准的方案。鉴于二线免疫治疗的持久疗效和良好应答率,专家意见仍倾向于对高PDL1表达的BRAF V600E突变型非小细胞肺癌使用靶向治疗作为初始治疗[17]。

然而,用于指导BRAF非V600E管理的数据较少。管理决策通常由关注其他恶性肿瘤的研究或主要包括V600E突变和少数非V600E患者的研究进行外推来指导的。

靶向治疗

理论上,许多非V600 BRAF突变是激酶受损的,因此被认为对RAF靶向治疗没有吸引力。Gautschi等人的一项研究检查了35例非小细胞肺癌BRAF突变患者,只有6种为非V600E (G466V、G469A、G469L、G596V、V600K和K601E)[18]。1例患者同时出现KRAS V12和BRAF V600K驱动基因突变,另1例患者伴有BRAF V600E的HER2扩增。未报告EGFR、ALK、MET、RET或ROS1同时发生的改变。在非V600E组,只有G596V患者对vemurafenib单药治疗部分缓解。

然而,Noeparast等人的一项研究对一个NSCLC患者队列进行了调查,结果表明,非V600 BRAF突变导致激酶活性升高或减弱会使dabrafenib和曲美替尼联合治疗具有敏感性[19]。

在试图了解损害非V600E突变的特定分子途径时,可考虑将其他非特异性靶向BRAF的TKIs作为未来研究的一个领域。例如,索拉非尼,一种具有多靶点的药物,可阻断C-RAF、B-RAF、c-KIT、FLT-3、RET、VEGFR-2、VEGFR-3和血小板源性生长因子受体的激活,在1例患者中显示出获益。Sereno等人报道了一例56岁的非小细胞肺癌女性患者BRAF G469R突变的病例[20]。该患者接受了七个疗程的大量预处理,并表现出对索拉非尼快速(10天内)和持续6个月的反应。ARAF S214C体细胞突变高水平表达,被认为是索拉非尼应答的一个指标。

还有翻译数据表明达沙替尼在激酶失活的非V600E BRAF突变中有支持作用机制[21]。

检查点抑制剂的作用

Dudnik等人研究了39例NSCLC患者[22]的BRAF突变与PD-L1表达之间的相关性。在研究人群中,发现42%~50%的患者PD-L1表达率较高,BRAF V600E和非V600E突变患者之间无统计学意义的差异。尽管免疫检查点抑制剂(ICI)的使用在驱动突变患者中经常存在争议,但研究组的ICI治疗的客观应答率(ORR)为25%~33%,中位无进展生存期(PFS)为3.7个月~4.1个月,与在二线治疗组接受ICI治疗的NSCLC患者中观察到的结果相当。注意到BRAF突变亚型和PD-L1表达水平均不影响OS。虽然本研究有设计限制,例如仅74%的患者接受了PD-L1检测,仅30%的患者接受了MSI状态和TMB评估,仅56%的患者接受了ICIs治疗,但作者得出结论,BRAF突变型NSCLC与PD-L1高表达、低/中TMB和MS稳定状态相关,ICIs对BRAF V600E和BRAF非V600E突变型NSCLC均具有有利的激活作用。

Guisier等人的另一项研究评估了107例患者的抗PD-1疗效,其中18例患者携带BRAF非V600E突变[23]。该队列中94%的患者在二线治疗中使用了该方法。有效率为35%,未达到应答持续时间。虽然受限于本回顾性研究的数量较少,但值得注意的是,BRAF非V600E患者对免疫检查点抑制剂(ICIs)的反应较BRAF V600E患者稍好(反应率分别为35%和26%)[23]。

这些发现需要进一步的研究来证实。我们假设ICI对BRAF突变的NSCLC中的疗效可能与吸烟状态有关,吸烟状态与较高的PD-L1表达和可能较高的突变负荷相关。

化疗的作用

在靶向治疗出现之前,BRAF突变的非小细胞肺癌采用传统的铂类联合化疗。在Cardarella等人于2013年发表的研究中,接受铂类联合化疗的BRAF突变晚期非小细胞肺癌患者的中位PFS为5.2个月,而野生型患者为6.7个月(P=0.622)[24]。在BRAF队列中,V600E突变患者的中位PFS较非V600E突变患者短,但没有统计学意义(4.1个月vs. 8.9个月;P=0.297)。

在这个个性化肺癌治疗的时代,化疗通常用于靶向和免疫治疗中疾病进展后的挽救性治疗。

未来方向

当前的一个研究领域是确定最终产生的靶向治疗耐药性的机制[2]。对于V600E突变型非小细胞肺癌,有两种机制:①全长BRAF V600E的缺失与突变蛋白的截短形式的表达一致,或②通过BRAF非依赖性的c-Jun信号介导的自分泌激活,增强EGFR信号通路。第二代BRAF抑制剂如PLX8394或联合使用BRAF和MEK抑制已被证明可通过BRAF V600E剪接变体的表达来防止耐药[11]。

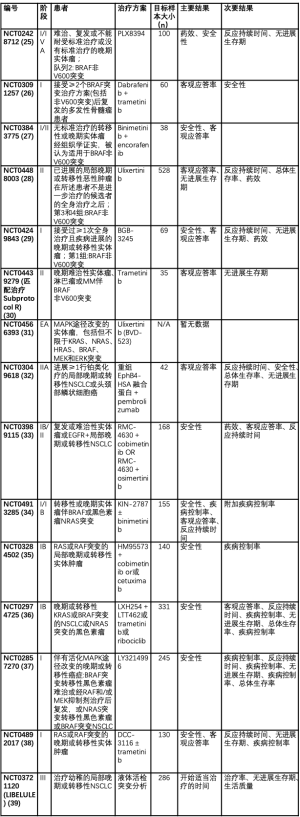

BRAF非V600E突变的耐药机制仍有待阐明,需要进一步研究以确定克服耐药性产生的适当策略,并指导治疗的适当顺序。表2总结了在该人群[25-23]中正在进行的试验。多数临床试验集中于BRAF V600E突变的非小细胞肺癌。然而,一些Ⅰ期临床试验已开放,可纳入非小细胞肺癌中所有形式的BRAF突变,并正在研究新的靶向治疗。

Full table

结论

BRAF非V600E突变型非小细胞肺癌罕见并且尚未完全确定其特征。它常发生于女性和吸烟者,通常与其他驱动突变相互排斥。

在没有任何其他驱动基因突变的情况下,患有BRAF非V600E突变的NSCLC患者应接受一线检查点免疫治疗、联合或不联合铂类化疗。鉴于这种突变的罕见性质,在没有明确的指导方针来指导临床决策的情况下,建议尽早纳入临床试验。对于无法接受标准化疗或免疫治疗药物且无法参加临床试验的患者,在某些情况下可根据特异性突变及其在BRAF基因中的位置使用BRAF和MEK酪氨酸激酶抑制剂。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://pcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pcm-21-49/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://pcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pcm-21-49/coif). NS serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Precision Cancer Medicine from September 2020 to August 2022. NS reports consulting fee from Boehringer Ingram. She has been on scientific advisory board for AstraZeneca, Amgen, Takeda, Genentech, Regeneron, and Pfizer within the last 36 months. None of these have any impact on the manuscript. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement:

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baik CS, Myall NJ, Wakelee HA. Targeting BRAF-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: From Molecular Profiling to Rationally Designed Therapy. Oncologist 2017;22:786-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002;417:949-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Safaee Ardekani G, Jafarnejad SM, Tan L, et al. The prognostic value of BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer and melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7:e47054. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Villaruz LC, Socinski MA, Abberbock S, et al. Clinicopathologic features and outcomes of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations in the Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium. Cancer 2015;121:448-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kinno T, Tsuta K, Shiraishi K, et al. Clinicopathological features of nonsmall cell lung carcinomas with BRAF mutations. Ann Oncol 2014;25:138-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frisone D, Friedlaender A, Malapelle U, et al. A BRAF new world. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2020;152:103008. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marchetti A, Felicioni L, Malatesta S, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3574-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Negrao MV, Raymond VM, Lanman RB, et al. Molecular Landscape of BRAF-Mutant NSCLC Reveals an Association Between Clonality and Driver Mutations and Identifies Targetable Non-V600 Driver Mutations. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:1611-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA 2014;311:1998-2006. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin L, Asthana S, Chan E, et al. Mapping the molecular determinants of BRAF oncogene dependence in human lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:E748-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tissot C, Couraud S, Tanguy R, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. Lung Cancer 2016;91:23-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rudin CM, Hong K, Streit M. Molecular characterization of acquired resistance to the BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib in a patient with BRAF-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:e41-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lito P, Pratilas CA, Joseph EW, et al. Relief of profound feedback inhibition of mitogenic signaling by RAF inhibitors attenuates their activity in BRAFV600E melanomas. Cancer Cell 2012;22:668-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Planchard D, Besse B, Groen HJM, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously treated BRAF(V600E)-mutant metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:984-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Planchard D, Smit EF, Groen HJM, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously untreated BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1307-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yau EH. BRAF V600E mutant, PD-L1 TPS 90% NSCLC: 1st line treatment with targeted therapy. Precis Cancer Med 2021;4:10. [Crossref]

- Gautschi O, Milia J, Cabarrou B, et al. Targeted Therapy for Patients with BRAF-Mutant Lung Cancer: Results from the European EURAF Cohort. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:1451-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noeparast A, Teugels E, Giron P, et al. Non-V600 BRAF mutations recurrently found in lung cancer predict sensitivity to the combination of Trametinib and Dabrafenib. Oncotarget 2016;8:60094-108. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sereno M, Moreno V, Moreno Rubio J, et al. A significant response to sorafenib in a woman with advanced lung adenocarcinoma and a BRAF non-V600 mutation. Anticancer Drugs 2015;26:1004-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng S, Sen B, Mazumdar T, et al. Dasatinib induces DNA damage and activates DNA repair pathways leading to senescence in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines with kinase-inactivating BRAF mutations. Oncotarget 2016;7:565-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dudnik E, Peled N, Nechushtan H, et al. BRAF Mutant Lung Cancer: Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression, Tumor Mutational Burden, Microsatellite Instability Status, and Response to Immune Check-Point Inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:1128-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guisier F, Dubos-Arvis C, Viñas F, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Patients With Advanced NSCLC With BRAF, HER2, or MET Mutations or RET Translocation: GFPC 01-2018. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:628-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cardarella S, Ogino A, Nishino M, et al. Clinical, pathologic, and biologic features associated with BRAF mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4532-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fore Biotherapeutics. A Phase 1/2a Study to Assess the Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of PLX8394 in Patients With Advanced Unresectable Solid Tumors. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02428712. Accessed September 16, 2021.

- Massachusetts General Hospital. An Open-label, Pilot Study of Dabrafenib and/or Trametinib in Patients With Relapsed and/or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03091257. Accessed September 16, 2021.

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. A Phase I/II Study of Binimetinib With Encorafenib in Patients With Non-V600 Activating BRAF Mutant Advanced Malignancies. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03843775. Accessed September 16, 2021.

- BioMed Valley Discoveries, Inc. A Two-Part, Phase II, Multi-center Study of the ERK Inhibitor Ulixertinib (BVD-523) for Patients With Advanced Malignancies Harboring MEK or Atypical BRAF Alterations. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04488003. Accessed September 16, 2021.

- MapKure, LLC. A First-in-Human, Phase 1a/1b, Open Label, Dose-Escalation and Expansion Study to Investigate the Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Antitumor Activity of the RAF Dimer Inhibitor BGB-3245 in Patients With Advanced or Refractory Tumors. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04249843. Accessed September 16, 2021.

- National Cancer Institute. MATCH Treatment Subprotocol R: Phase II Study of Trametinib in Patients With BRAF Fusions, or With NonV600E, Non-V600K BRAF Mutations. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04439279. Accessed September 16, 2021.

- xCures. Expanded Access to Ulixertinib (BVD-523) in Patients With Advanced MAPK Pathway-Altered Malignancies. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04566393. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- University of Southern California. A Phase IIa Trial of sEphB4-HSA in Combination With Anti PD-1 Antibody (Pembrolizumab, MK3475) in Patients With Non-small Cell Lung and Head/Neck Cancer. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03049618. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- Revolution Medicines, Inc. A Phase 1b/2, Open-Label, Multicenter Dose-Escalation and Dose-Expansion Study of the Combination of RMC-4630 and Cobimetinib in Adult Participants With Relapsed/Refractory Solid Tumors and a Phase 1b Study of RMC-4630 With Osimertinib in Participants With EGFR Mutation Positive, Locally Advanced or Metastatic NSCLC. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03989115. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- Kinnate Biopharma. A Phase 1/1b Open-label, Multicenter Study to Investigate the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Antitumor Activity of KIN-2787 in Participants With BRAF and/or NRAS Mutation-positive Solid Tumors. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04913285. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- Hanmi Pharmaceutical Company Limited. A Phase Ib, Open-label, Multicenter, Dose Escalation Study of the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of HM95573 in Combination With Either Cobimetinib or Cetuximab in Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03284502. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals. A Phase Ib, Open-label, Multicenter Study of Oral LXH254-centric Combinations in Adult Patients With Advanced or Metastatic KRAS or BRAF Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer or NRAS Mutant Melanoma. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02974725. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- Eli Lilly and Company. A Phase 1 Study of an ERK1/2 Inhibitor (LY3214996) Administered Alone or in Combination With Other Agents in Advanced Cancer. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02857270. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- Deciphera Pharmaceuticals LLC. A Phase 1, First-in-Human Study of DCC-3116 as a Single Agent and in Combination With Trametinib in Patients With Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors With RAS or RAF Mutations. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04892017. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- Centre Leon Berard. A Randomized Phase III Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Feasibility and Clinical Relevance of Liquid Biopsy in Patients With Suspicious Metastatic Lung Cancer. Available online: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03721120. Accessed February 15, 2022.

熊晨

复旦大学附属肿瘤医院(更新时间:2023-05-05)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Abuali I, Lee CS, Seetharamu N. A narrative review of the management of BRAF non-V600E mutated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Precis Cancer Med 2022;5:13.