乳腺癌患者的药物相关毒性:通往精准治疗的一条新道路?——叙述性综述

介绍Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

乳腺癌(BC)作为最常被诊断出的癌症,也是世界范围内女性死亡的主要原因之一[1]。多年来,已经有多个指标被引入不同分期乳腺癌的管理中,也带来了显著改善的生存结果。事实上,传统的化疗、内分泌治疗、靶向药物和免疫治疗的联合治疗是目前临床不可分割的一部分,并且效果已在临床试验中得到验证[2]。治疗方法可以根据肿瘤生物学特征、疾病负担、患者的临床特征、并发症和偏好等进行定制。不幸的是,所有的药物都具有不良反应(AE),而且并非所有患者都对治疗有反应;此外,其中一些药物不仅没有临床获益处,还会产生严重的毒性反应。因此,选择能高效挑选出特定治疗方式“受众”患者的因素是非常重要的。

最近,以根据患者的临床和分子特征进行分类为基础的“精准肿瘤学”的概念,渐渐体现出重要性[3]。其背后的科学原理是识别出患者基因组中的癌症驱动基因突变特征,然后选择特定的靶向药物抑制对应的基因突变产物[4]。基因组测序结果可用于对癌症进行分类、预后预测和靶向治疗。二代测序的出现则允许快捷、高效的大型基因组测序成为癌症基因组学的重要组分[5]。

在个性化治疗中鉴定临床上表达有意义的基因集标记,不仅可以用提高整体生存,也可以降低药物毒性[6]。然而,在临床实践过程中,并非所有癌症中心都可以为患者提供基因组检测,这需要进一步确定方便获取的临床因素来提高患者筛选的效率。

因此,毒性特征是个性化治疗过程中一个值得研究的点。在此综述中,我们着眼于精准治疗,并针对乳腺癌治疗过程中的主要抗癌药物进行安全性及临床可预测性的展望,并把患者的临床特征纳入考虑。我们将按照叙述性审查报告清单中要求的那样阐述接下来的内容。

方法Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

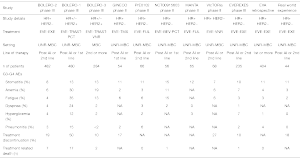

我们对PubMed和可获得的医学肿瘤学大会资源进行了广泛的文献研究,内容涉及针对BC的定制抗癌疗法、毒性概况和潜在特定药物相关毒性的诱发因素。我们纳入文献的时间跨度为1997年1月1日−2021年12月31日。文献语言仅限于英文(表1)。我们的研究侧重于精准医疗和潜在的患者分类标志物的探索。

Full table

蒽环类Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

蒽环类药物是乳腺癌治疗药物中的重要基石[7]。心脏毒性、骨髓抑制、恶心和呕吐是主要的药物不良事件,已经有各种研究评估其潜在的易感因素。Chen等人在211年的分析表明:在接受表柔比星−环磷酰胺−西他赛化疗治疗的BC患者中,相较于TT基因型(P=0.038)型与CT/TT基因型(P=0.019),rs2420946 CC基因型与成纤维细胞生长因子受体2(FGFR2)有着更加显著的相关性和更高的AE发生率,类似结果发现FGFR2 rs2981578 AG基因型与GG基因型之间(P<0.0001)[8]。

心脏毒性

Vaitikus等人确定了HFE基因H63D单核苷酸多态性(SNP)与81例接受以多柔比星为主的化疗方案的BC患者的亚临床心脏损伤之间有着显著关联(P<0.005)[7]。NFKBIL1、TNF−a、ATP6V1G2−DDX39B、MSH5、MICA、LTA、BAT1和NOTCH4的18个相关的SNP被认为可能与阿霉素诱导的心脏毒性有关[9]。在三项Ⅲ期辅助乳腺癌试验的3 431例患者中进行的全基因组关联研究发现,rs28714259 SNP与蒽环类药物诱导的充血性心力衰竭(CHF)相关[10]。Vulsteke等人发现6个周期的5−氟尿嘧啶、表柔比星和环磷酰胺与3个周期相比(OR=1.3,95%CI:1.1~1.4,P<0.001),ABCC1 rs246221 T-allele的杂合状态与同合状态相比(OR=1.6,95%CI:1.1~2.3,P=0.02),与早期BC(EBC)中左心室射血分数(LVEF)减少>10%有显著关系[11]。

另一项研究检测到UGT2B7-161 T等位基因状态是表柔比星−环磷酰胺−多西紫杉醇辅助化疗期间较低的心脏毒性发生率的潜在依赖性生物标志物(P=0.004)[12]。

血液学毒性

在Cui等人的一项包含194例接受辅助蒽环类药物治疗的乳腺癌患者的研究中,CBR1 rs20572 (C>T)、ABCG2 rs2231142 (G>T) SNPs涉及蒽环类药物的药代动力学,并且两个多态性等位基因的组合与白细胞减少症风险降低(OR=0.412,95%CI:0.187~0.905,P=0.025)和中性粒细胞减少症(OR=0.354,95%CI:0.148~0.846,P=0.018)显著相关。此外,携带CBR1 rs20572多态性等位基因T(OR=0.058,95%CI:0.006~0.554,P=0.008)或AKR1A1 rs2088102多态性等位基因C结合ABCG2 rs2231142(G>T)(0.065,95%CI,0.006~0.689,P=0.022)加上SLC22A16 rs6907567 (A>G) 突变(OR=0.037,95%CI:0.004~0.36, P=0.015)的患者显示出极低的3~4级贫血风险。因此,这些SNP可能有助于确定那些有着较低血液系统不良事件发生可能性的患者[13]。

胃肠道毒性:恶心和呕吐

一项包含110例接受表柔比星附加或者不附加(+/-)环磷酰胺治疗的乳腺癌患者的研究,探索了5−羟色胺受体3(HTR3C)基因在化疗引起的恶心和呕吐(CINV)中的作用,K163N (HTR3C)的基因变异类型与呕吐事件相关(P=0.009)[14]。Tsuji等人表示TACR1 1323TT SNP,即能编码神经激肽 1 受体的基因,可能是延迟CINV发展的遗传风险因素(OR=2.57;P=0.014)[15]。

氟嘧啶类Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

超过30%接受氟嘧啶治疗的患者有严重的治疗相关不良反应,例如腹泻、手足综合征、骨髓抑制和粘膜炎[16]。与氟嘧啶相关的毒性通常是由于编码二氢嘧啶脱氢酶(DPYD)的基因中存在遗传变异,DPYD是参与氟嘧啶降解的主要酶[17,18]。3%~5%的欧洲和北美人的DYPD缺乏活性(降低比例约为50%),如果用全剂量氟嘧啶治疗,此类患者发生严重氟嘧啶药物相关不良事件的风险将显著上升[19]。实际上,四种DPYD相关的基因突变被认为在临床上与严重毒性相关,具有显著的统计学意义:c.1905+1G>A、c.2846A>T、c.1679T>G和c.1236G>A[20]。多年来,氟嘧啶给药前的常规DPYD基因型筛查并不是乳腺癌患者管理的护理标准。然而,最近的研究表明,在乳腺癌中采用常规DPYD基因型筛查应用也具有显著的临床和经济利益[21-25]。值得注意的是,随着在HER2受体阴性的Ⅰ−ⅢB期,在手术或者新辅助化疗后无完全病理反应或有完全反应但淋巴阳性的乳腺癌患者中引入与结直肠癌治疗相似剂量的卡培他滨辅助治疗,这一点变得越来越重要[26]。

由于这些原因,EMA强烈建议在开始输注氟尿嘧啶或相关前药(卡培他滨和替加氟)治疗之前进行DYPD基因检测[27]。根据DYPD基因突变的情况,结合指南和建议调整氟嘧啶的剂量。

抗HER2药物Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

在过去的20年中,抗HER2的靶向药物极大地改变了HER2阳性乳腺癌患者的临床结果[28]。

心脏毒性

心脏毒性是与抗HER2治疗相关的最受关注的AE之一,无论是在症状事件(如CHF)还是在无症状事件(如LVEF降低)方面。心脏AE已在EBC(早期乳腺癌)和转移性BC(MBC)中得到广泛研究[29]。在获得批准作为MBC一线治疗药物的关键Ⅲ期随机临床试验(RCT)中,抗HER2单克隆抗体(mAb)曲妥珠单抗显示出更高的心功能障碍和纽约心脏协会级别的CHF发生率Ⅲ或Ⅳ(27% VS. 16%)与基于蒽环类药物的治疗相关时,与仅基于蒽环类药物的化疗(8% VS. 3%)相比,这些AE的发生率在曲妥珠单抗加紫杉醇组中较低(分别为13%和2%)[30]。这些数据通过一项荟萃分析重新确定了维度,该荟萃分析包括该随机对照试验和其他六项后续随机对照试验,共有1 497名HER2阳性女性,在接受曲妥珠单抗治疗的患者中,CHF风险显著增加,LVEF降低[风险比(RR)分别为3.49和2.65],据报道,在接受曲妥珠单抗治疗的患者中,4.7%的患者发生了严重的心脏AE[31]。

另一项比较随机对照试验与队列研究的荟萃分析发现,与RCT患者相比,更密切地反映真实治疗人群的队列研究中患者发生严重心脏AE的风险更高(4.4% VS. 2.8%),尽管总体而言,在4.28%的MBC中观察到严重的心脏毒性患者。该研究还证实,曲妥珠单抗与基于蒽环类药物的方案一起使用与严重心脏毒性的比例高于单独使用基于紫杉类药物的方案(2.9% VS. 0.9%)[32]。

一项调查了8项辅助治疗相关的RCT实验的荟萃分析(共涉及11,991名HER2阳性 EBC 女性)显示,与对照组相比,接受含曲妥珠单抗方案治疗的患者发生CHF(RR=5.11, P<0.00001)和LVEF下降(RR=1.83,P=0.0008)的风险显著增高。曲妥珠单抗组的CHF发生率和LVEF下降发生率分别为2.5%和11.2%,而对照组分别为0.4%和5.6%[33]。在另一项包含6项RCT的荟萃分析中,发现接受曲妥珠单抗治疗人群发生NYHA Ⅲ/Ⅳ CHF的风险比未接受曲妥珠单抗的患者高3.04倍(P<0.00001)[34]。主要RCT的长期安全性分析还发现,在含曲妥珠单抗的方案中,心脏毒性的累积发生率和心脏AE的总体风险更高[35-37]。一项包含三项临床试验的综合分析结果调查了曲妥珠单抗联合蒽环类药物在新辅助治疗中的安全性和有效性,结果与其他治疗方式(辅助治疗和转移性肿瘤)治疗没有差异,证实了联合治疗的心脏毒性风险增加[38]。

随着曲妥珠单抗的暴露时间更长[35]和更高剂量的给药[34],心脏不良事件的风险似乎显著增加。年龄≥60岁、基础LVEF介于50%~54.9%之间以及使用抗高血压药物也与心脏毒性风险显著增加有关,因此这类BC患者值得特别关注[36]。心脏AE主要发生在曲妥珠单抗给药期间,其中许多是可逆的,在86.1%的曲妥珠单抗治疗且有症状性心力衰竭事件的患者中观察到完全或部分恢复[35,39]。在转移性、辅助性和新辅助性治疗背景中,与曲妥珠单抗加标准化疗相比,帕妥珠单抗(一种人源化抗HER2 mAb)与曲妥珠单抗一起使用不会增加心功能不全的发生率[40−44]。拉帕替尼是一种EGFR和HER2的双酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(TKI),与MBC中更大的心脏AE风险无关,这一点是在关键的Ⅲ期试验中得到的结果,并通过一项涉及来自不同临床的3 689名接受拉帕替尼治疗的患者的荟萃分析得到证实,其中心脏AE的发生率为1.6%[45,46]。来自EBC随机对照试验的数据也一致[47−48]。曲妥珠单抗(T-DM1),一种由与细胞毒性抗微管剂连接的抗HER2 mAb组成的抗体药物偶联物,具有明显的心脏毒性特征[49,50],曲妥珠单抗−deruxtecan(由抗 \HER2 mAb、可切割的四肽基接头和细胞毒性拓扑异构酶 I 抑制剂组成的抗体药物偶联物)[51]和高选择性TKI[52]也具有明显的心脏毒性特征。目前为止暂没有证据表明来那替尼具有心脏毒性,这是一种针对EGFR、HER2和HER4的TKI[53]。

我们强烈建议在开始HER2靶向治疗之前,立即通过超声心动图和/或多门采集扫描或磁共振成像进行基线心电图和基线LVEF测量,以识别未来心血管并发症风险较高的患者个体。接受曲妥珠单抗辅助治疗的无症状患者应每3个月重复包括心脏成像在内的常规监测,以便在治疗期间及早发现心脏毒性,并在停止治疗后每6个月重复一次,直至最后一次给药后2年。MBC中接受抗HER2治疗且无症状的患者还应接受心脏影像学检查。如果因为出现有症状的左心室心功能不全而停止抗HER2靶向治疗,则应在4周后重复测量LVEF。最好使用相同的成像方式和在相同的设施进行连续监测[54−58]。心脏损伤的血清酶也被研究作为心脏毒性的潜在生物标志物。肌钙蛋白I已被证明可预测曲妥珠单抗治疗患者的LVEF降低风险和心脏AE风险,尤其是那些接触过蒽环类药物的患者。在肌钙蛋白I水平≥0.08 ng/mL(HR=22.9,非恢复性HR=2.88)和蒽环类药物治疗结束时高敏肌钙蛋白T水平升高>14的患者中观察到发展曲妥珠单抗诱导的心脏毒性较高[59−64]。NeoALTTO子研究BIG 1-06表明,仅在少数接受曲妥珠单抗和/或拉帕替尼的蒽环类初治患者中检测到肌钙蛋白T和proBNP,因此,它们可能不是该背景患者心脏毒性风险的有效早期预测指标[65]。由于大多数关于肌钙蛋白的研究都集中在接受过蒽环类药物治疗的患者身上,因此需要进一步的研究来探索这种生物标志物的作用及其在临床实践中的应用。至于FC γ受体(FCGR)多态性的潜在影响,大多数研究都集中在抗HER2功效上,并提供了关于FCGR2A和FCGR3A作用的对比结果[66,67]。关于FCGR SNP和毒性的数据有限。在Cresti等人的一项研究中,辅助化疗后每3周接受一次曲妥珠单抗治疗的101例HER2阳性EBC患者中,FCGR2A His131Arg SNP与曲妥珠单抗相关心脏毒性的发生显著相关[68]。罗卡等人发现曲妥珠单抗相关的心脏毒性与HER2−I655V基因型之间具有重要关联(P=0.025),而与FCGR2A−H131R或FCGR3A−V158F SNP无关[69]。虽然这是一个有趣的现象,但这些发现需要更广泛的研究才能得到证实。

肺毒性

曲妥珠单抗−deruxtecan与13.6%的间质性肺病(ILD)发生率相关,4例死亡归因于治疗相关的ILD[51]。患者应监测ILD/肺炎的体征和症状,疑似ILD/肺炎的病例应通过计算机断层扫描(CT)扫描进行评估。在无症状ILD/肺炎(1级)的情况下,应暂停给药,直至恢复至0级后可以恢复给药,而对于有症状的ILD/肺炎(≥2级),建议永久停用曲妥珠单抗,及时给予皮质类固醇药物至少14天或直到临床症状和胸部CT全部恢复正常[51,70,71]。在KATHERINE试验中,T−DM1组2.6%的患者发生肺炎,而曲妥珠单抗组为0.8%[50]。曲妥珠单抗与mTOR抑制剂联用时,ILD发生率更高:在BOLERO−3试验中,接受曲妥珠单抗与长春瑞滨和依维莫司的患者的ILD发生率为9.2%,而接受曲妥珠单抗长春瑞滨和安慰剂的患者的ILD发生率为3.9%,尽管3~4级ILD患者在两组中相似[72]。

胃肠道和皮肤毒性

以HER2为靶点的TKI具有较高的胃肠道和皮肤毒性发生率。在针对接受拉帕替尼治疗的MBC患者的关键RCT中,腹泻和皮疹是拉帕替尼加卡培他滨组中最常见的治疗相关AE(任何级别和≥3级)[45]。在新辅助和辅助治疗中,与含曲妥珠单抗的方案相比,含拉帕替尼的方案最常与3级腹泻和皮疹相关[47,48]。在MBC中,与含曲妥珠单抗的方案相比,图卡替尼和来那替尼的胃肠道和皮肤毒性发生率更高[52,73],在辅助治疗中,与安慰剂相比,来那替尼也体现出较的高胃肠道和皮肤毒性[37]。在MBC和EBC中,与曲妥珠单抗相比,曲妥珠单抗联合帕妥珠单抗似乎与更高发的任何级别和≥3级腹泻相关[42,43,74]。

肝毒性

在用图卡替尼[52]、来那替尼[53]和拉帕替尼治疗期间观察到肝毒性,主要表现为血清转氨酶或胆红素浓度的无症状增加。在接受T−DM1治疗的患者中观察到严重的肝胆疾病,例如肝脏的结节性再生性增生[49,50],在这些情况下,必须永久停用T−DM1[75]。

血液学毒性

T−DM1最常见的3~4级AE之一是血小板减少症[49−51]。建议在每个治疗周期之前进行常规监测并进行血液学完整评估。

PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

依维莫司

磷酸肌醇3−激酶(PI3K)信号通路在细胞的生长、增殖、迁移和死亡中起着至关重要的作用。PI3K突变经常参与BC发展。哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白(mTOR)是PI3K相关激酶蛋白之一。依维莫司是一种口服mTOR抑制剂,用于激素受体(HR)阳性和HER2阴性BC的绝经后妇女,可辅助非甾体芳香化酶抑制剂(AI)治疗期间的复发或在预先治疗的晚期进展疾病[76]。几项研究评估了依维莫司与其他药物联合使用的安全性和可行性[72,77−86](表2)。

Full table

在BOLERO−2试验中,485例患者被随机分配接受依维莫司加依西美坦治疗,19%的病例因AE停用依维莫司。总体而言,23%的患者发生了严重的AE。最常见的3级和4级AE为:口腔炎(8%)、贫血(6%)、呼吸困难(4%)、高血糖(4%)、疲劳(4%)和肺(3%),发生了7起与治疗相关的死亡[77]。同样,在针对接受依维莫司加依西美坦治疗的HR+、HER2-、MBC患者的各种试验和真实回顾性研究中观察到类似的毒性[84−86]。

在临床实践中,毒性通常会中断治疗直至症状改善至≤1级和/或用药剂量减少[87]。威廉森等人评估了20例接受依维莫司和依西美坦联合治疗的BC患者中具有抗肿瘤反应的外周血免疫细胞亚群的与肺毒性发生之间的关系。与其他患者相比,出现肺毒性反应的BC患者的基线NKT细胞(CD3+、CD56+)水平相对较高(6.0% VS. 1.3%,P=0.0068,59 k ×109/L VS 12 k ×109/L,P=0.0081);毒性反应发生时NKT细胞水平也较高(5.2% VS 1.2%,P=0.0106,47 k ×109 /L VS 16 k ×109 /L,P=0.0466)。基线NKT细胞百分比可以以0.78的敏感性和1.0的特异性预测肺毒性,但这些数据仍需要进一步验证[88]。

帕斯夸尔等人对90例绝经后接受依西美坦依维莫司治疗后发生AI的HR阳性、HER2阴性、MBC的患者进行了探索性药物遗传学研究分析,以评估SNP对AE发生和结果的作用。他们对涉及依维莫司药代动力学和药效学的12个SNP进行了基因分型分析,并研究了其与依维莫司血浆浓度、显著AE和随之而来的药物方案修改、无进展生存期和总生存期的关联。与其他患者相比,携带CYP3A4 rs35599367 SNP(CYP3A4*22等位基因)的患者血浆药物水平升高(P=0.019),ABCB1 rs1045642携带者的黏膜炎症风险增加(P=0.031),而PIK3R1 rs10515074和RAPTOR rs9906827患者发生高血糖(P=0.016)和非感染性肺部炎症(P=0.024)的风险增加。这些结果表明SNP可能会影响MBC中的依维莫司效果[89],因此对并发症如糖尿病或肺病史的患者给予关注至关重要。尽管如此,特定的患者人群以及没有这些并发症的患者都可以从治疗中受益。

阿培利司

阿培利司是一种口服选择性PI3K α抑制剂[90]。在SOLAR−1 Ⅲ期试验中对HR阳性、HER2阴性的晚期化疗初治BC、经AI预处理的绝经后女性或男性患者进行了阿培利司治疗相关的研究。在SOLAR−1纳入的572例患者中,284例(169例PIK3CA突变型和115例野生型)患者接受了阿培利司联合Fulvestrant治疗。所有级别最常见的AE为:高血糖(63.7%;G3/4:36.6%)、腹泻(57.7%;G3/4:6.7%)、恶心(44.7%)、食欲下降(35.6%)和皮疹(35.6%;G3/4:9.9%)或斑丘疹(14.1%;G3/4:8.8%)。AE导致25%的患者永久停药。没有发生与治疗相关的死亡[91]。

随机、双盲Ⅲ期NEO-ORB试验招募了HR阳性HER2阴性的可切除BC的绝经后妇女,包括符合新辅助治疗条件的患者,并评估了阿培利司联合来曲唑的疗效,不允许患者事先进行局部或全身治疗。

在阿培利联合来曲唑组中观察到的AE为:高血糖(任何级别54%;G≥327%)、腹泻(任何级别52%)、皮疹(任何级别45%;G≥312%)、恶心(任何级别44%),疲劳(任何级别41%),口腔炎(任何级别33%),食欲下降(任何级别31%),脱发(任何级别22%)、头痛(任何级别20%)和斑丘疹皮疹(G≥38%)。没有发生与治疗相关的死亡[92]。最近,Rodon及其同事报告了X2101和SOLAR-1的汇总分析,风险分析基于505例接受阿培利司治疗后引起基线升高的实体癌(包括BC)患者的特征。风险建模确定了5个基线因素,即禁食血浆葡萄糖、体重指数、HbA1c、单核细胞计数和年龄,这些因素与G3/4高血糖的较高概率相关。高危患者表现出更高的阿培利司修饰率和抗高血糖发生率。该模型可能有助于识别具有较高升血糖风险、接受阿培利司治疗的BC患者[93]。

虽然在大多数情况下观察到的铅毒性呈现3/4级,在停止治疗后,它们会因治疗的暂时停止而消退。因此,阿培利司和依维莫司似乎都是安全的。

聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

在BRCA突变BC患者的靶向治疗中,PARPi代表了主要的创新方法之一。目前已经研究了几种PARPi,包括olaparib、talazoparib、niraparib、veliparib和rucaparib。它们的作用机制并不单一,因此它们的功效与不同的途径密切相关。特别是,它们与PARP酶家族的相互作用至关重要[94]。

血液学毒性

在临床实践中,血液学毒性在PARPi给药期间非常常见,它们通常出现在治疗的早期阶段[95]。贫血最常见,其次是血小板减少症和中性粒细胞减少症。在三项Ⅲ期维持试验中,44%接受奥拉帕尼的患者、50%接受尼拉帕尼的患者和37%接受鲁卡帕尼的患者报告了全级别贫血。niraparib(25%)的3级和4级AE更常见,其次是rucaparib(19%)和olaparib(19%)。任何级别的血小板减少症在niraparib组中更常见(niraparib组61% vs. rucaparib组28% vs. olaparib组14%)。全级别中性粒细胞减少症发生在18%~30%的受试者中,尼拉帕尼(20%)的3/4级AE更高[96−98]。

对于所有开始PARPi或需要改变剂量的患者,建议每月进行一次全血细胞计数以评估血液学AE。FDA niraparib指南建议在治疗开始的第一个月,每周检查一次血液学毒性,尤其是血小板浓度[99−101]。实际上,对于这种AE,没有经过验证的预测性生物标志物可用。对ENGOT-OV16/NOVA试验进行了一项回顾性分析,该试验在对铂类化疗完全或部分反应的复发性上皮性卵巢、输卵管癌或原发性腹膜癌患者中维持尼拉帕尼,以评估预测剂量减少的临床参数。基线血小板计数<150,000/µL和基线体重<77 kg被确定为3级血小板减少症发生率增加和剂量减少至200 mg或100 mg的危险因素。这些患者的PFS不受剂量变化的影响,这表明他们可能受益于200 mg/天的起始剂量。虽然是回顾性的,但这些数据可能是进一步研究BC患者这一主题的起点[102]。

胃肠道毒性

胃肠道AE很常见,最常见的是恶心、便秘、呕吐和腹泻[99−101]。他们的管理策略与化疗引起的胃肠毒性类似,使用促动力药和止吐药如甲氧氯普胺,地塞米松[103,104]。神经激肽−1抑制剂受体拮抗剂,不应该与奥拉帕利联用,因为它是一种有效的CYP3A4抑制剂,可能会影响奥拉帕利的血浆浓度[105]。

肾毒性

在ARIEL3中给予rucaparib会导致15%患者的肌酐(任何级别)水平在治疗的前几周增加,而安慰剂组为2%。rucaparib抑制参与肌酐分泌的肾脏转运蛋白MATE1和MATE2-K[96]。在研究SOL0218中,21/195例接受奥拉帕尼治疗的患者有1~2级肌酐增加(无3~4级),只有1%的安慰组患者没有引起血清肌酐增加[98]。这种改变可能无法反映肾小球滤过率(GFR)的真实下降。如果GFR合适(即GFR是典型的或与肌酐升高不一致),则不需要减少或中断剂量[95]。

疲劳

59%~69%接受PARPi治疗的患者感受到任何等级的疲劳[96−98]。专家推荐非药物方法,即运动、按摩疗法和认知行为疗法[95]。

临床实验室异常

最常见的实验室异常是高胆固醇血症和血清丙氨酸氨基转移酶和天冬氨酸氨基转移酶水平升高。这些影响通常是暂时的[98]。应特别小心既往有肝功能障碍的患者服用此类药物。在持续性高胆固醇血症的情况下,可能需要基于他汀类药物的治疗[95]。

其他毒性

其他不太常见的AE可能包括头痛和失眠的神经系统症状。潜在的机制尚未完全了解,但一些临床前研究已经确定了PARP1在维持昼夜节律基因转录中的作用,PARP1抑制导致关键的昼夜节律转录成分断裂[106]。

对于轻微症状,进行对症治疗就足够了,而对于更严重的症状,根据FDA指南,可能需要根据每个PARPi[99−101]特性进行计量减少。

报告的呼吸道症状包括呼吸困难、咳嗽、鼻咽炎和更罕见的肺炎[96−98]。导致这些症状的机制尚不清楚。临床前数据仅显示PARP激活与支气管高反应性和气道重塑有关[107]。疑似或确诊肺炎的处理应根据公认的药物性肺炎指南进行[108]。

其他更罕见的不良反应包括肌肉骨骼毒性(关节痛、背痛)、皮肤毒性(光敏反应、瘙痒、皮疹、外周水肿)和心血管毒性(高血压、心动过速、心悸)[96−98]。对于最后提到的,服用尼拉帕尼,尤其是有心血管并发症的患者,应在第一年时每月进行一次血压和心率监测,之后定期检查[101]。

继发性恶性肿瘤

由于PARP抑制的主要机制涉及干扰DNA修复途径,因此包括骨髓增生异常综合征和急性髓细胞白血病在内的严重AE是需要停止治疗的,尽管发病率很低且出现在长期治疗后(0.5%~1.4%)。在所有临床试验中,所有发生这些AE的患者之前都接受过铂类化学疗法或其他DNA损伤药物的治疗,因此很难将PARPi定义为主要的原因[96−98]。

免疫疗法Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

程序性细胞死亡−1/程序性死亡配体−1(PD−1/PD−L1)拮抗剂的临床活性在三阴性BC(TNBC)的治疗中得到证实[109]。在IMpassion 130试验中,抗PD-L1 atezolizumab和nab-paclitaxel的联合使用显示出可接受的安全性,并被批准作为PD-L1表达>1%的不可切除的局部晚期或转移性TNBC患者的一线治疗方案。在atezolizumab组中,49%的患者出现3~4级AE。atezolizumab组中6%的患者发生周围神经病变,这是由于毒性而停止治疗的主要原因(4%),但它也被认为与紫杉烷相关的累积性反应相关。特别值得关注的是,atezolizumab组和安慰剂组之间具有显著差异的AE是任何级别的皮疹、甲状腺功能减退、甲状腺功能亢进、肺炎和肾上腺功能不全。atezolizumab组中与治疗相关的死亡发生在<1%的患者中(一例是由于自身免疫性肝炎,一例是仅与白蛋白结合型紫杉醇有关的感染性休克)和安慰剂组中<1%的患者(肝功能衰竭)[110,111]。在新辅助治疗中,atezolizumab的安全性与MBC一致。在IMpassion031试验中,atezolizumab组7%的患者发生甲状腺功能减退,而对照组为1%。因AE停用atezolizumab或安慰剂的患者人数分别为13%和11%[112]。

KEYNOTE-522试验评估pembrolizumab联合化疗的数据报告了38.9%患者的免疫相关AE发生率,包括甲状腺功能减退(任何级别:14.9%;>3级:0.4%)、甲状腺功能亢进(任何级别:5.1%;>3级:0.3%)、严重皮肤反应(任何级别:4.4%;>3级:3.8%)和肾上腺功能不全(任何级别:2.3%;>3级:1.3%)。即使可控,与免疫检查点抑制剂相关的AE也可能导致持续的改变,包括甲状腺疾病和肾上腺功能衰竭,在不确定的时间内可能需要激素替代治疗[113,114]。在GeparNuevo试验中,在标准新辅助化疗中添加durvalumab并未导致AE的发生率更高,但甲状腺功能障碍(任何级别)除外,这种情况在durvalumab上更常见(47%),7例患者患有甲状腺功能减退,9例患者患有甲状腺功能亢进,1例患者患有垂体炎[115]。

在TONIC试验中,对转移性TNBC患者进行为期2周的化疗或放疗诱导后,纳武单抗与任何先前未报告的毒性无关。28%的患者(3级:3%)发生任何级别的诱导治疗相关AE,19%的患者发生3~5级的免疫相关AE[116]。

从黑色素瘤和非小细胞肺癌的研究中获得了关于潜在毒性预测因子的可用数据,这些数据可能有助于患者的选择。在Krishnan等人的回顾性分析中,治疗期间出现嗜酸性粒细胞增多的患者更可能出现毒性(P=0.042),因此建议开展进一步的前瞻性研究[117]。据报道,白细胞计数增加和相对淋巴细胞计数减少与纳武利尤单抗的肺/胃肠道毒性独立相关[118]。基线抗甲状腺球蛋白抗体和抗甲状腺过氧化物酶抗体水平在抗PD-1治疗期间的早期升高,则与甲状腺炎和甲状腺功能障碍的发展有关[119−121]。此外,在预先存在类风湿因子阳性的患者中更频繁地观察到皮肤毒性[120,122]。需要进一步的前瞻性设计研究来证实这些发现和评估它们在临床实践中的潜在应用。

内分泌治疗Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

他莫昔芬作为选择性雌激素受体调节剂[123]。在乳腺组织中,它通过与雌激素受体竞争性结合发挥抗雌激素作用。在其他组织中,他莫昔芬具有雌激素激动作用,例如,通过刺激子宫内膜增殖,增加子宫内膜恶性肿瘤的风险。其他报告的不良反应为:头晕、头痛、抑郁、精神错乱、疲劳和肌肉痉挛[124]。血栓栓塞风险增加可能与他莫昔芬引起的循环凝血抑制剂有关,即降低抗凝血酶III、蛋白C和蛋白S水平[125,126]。科学证据表明,长期服用他莫昔芬与女性继发性子宫内膜癌有关。根据现有结果,随着他莫昔芬治疗时间的延长,子宫内膜癌的风险会增加2~4倍[127]。在ATLAS研究中,评估了他莫昔芬辅助治疗时间的持续10年的数据,继续治疗的患者在第5~14年期间子宫内膜癌的累积风险为3.1%(死亡率为0.4%),而在5年后停止治疗的患者子宫内膜癌的累积风险则为1.6%(死亡率为0.2%)[128]。

CYP2D6酶对于将他莫昔芬转化为主要活性代谢物内多昔芬至关重要。CYP2D6基因改变可能是酶活性异常的原因,因此构成了超快代谢者(活性增加)、中间代谢者(活性降低)、弱代谢者(活性缺失)的特征。最后两种情况可能会导致内多昔芬减少血液水平,因此降低他莫昔芬功效[129]。

第三代人工智能——阿那曲唑、来曲唑和依西美坦是HR阳性、EBC和MBC患者的有效内分泌治疗药物[130,131]。雌激素对多种组织发挥生理作用,包括骨骼、免疫系统、中枢神经系统和心血管系统[132],它们可能会引发保护性心血管效应,正如与男性相比,首次心血管疾病年龄越大,冠心病发病率越低[133,134]。他莫昔芬对心血管系统的保护作用与雌激素样活性(α受体激动剂)有关,导致低密度脂蛋白(LDL)胆固醇和同型半胱氨酸血清水平的降低。事实上,一项对12项研究进行的荟萃分析显示,他莫昔芬与安慰剂组相比,可降低心脏病发病率(HR=0.62,95%CI:0.41~0.93)。在评估前期AI与前期他莫昔芬的两项试验的综合分析中,AI与心血管疾病显著相关(OR=1.30,95%CI:1.06~1.61,P=0.01)[135−137]。在比较从他莫昔芬转换为AI与前期AI的研究中报告了一致的发现(OR=1.37,95%CI:1.05~1.79,P=0.02)[138]。AI对心血管系统潜在负面影响的生物学原理主要与它们对脂质代谢的作用有关。与他莫昔芬相反,AI会提高血清胆固醇水平,这可能会导致更高的心血管疾病发生风险,特别是在预先存在动脉高血压、糖尿病和肥胖症的情况下[139]。

在初始他莫昔芬治疗5年后使用他莫昔芬或AI进行的延长辅助内分泌治疗,已被证明可提高EBC的无病生存期[108,140-142]。EBCTCG荟萃分析表明,在辅助治疗的前5年使用AI治疗会优于他莫昔芬单药治疗[143]。在2019年发表的一项基于文献的荟萃分析中,包含了8项试验,较长的AI治疗与较高的骨痛RR(RR=1.26,RD=0.04,P=0.003)、骨折(RR=1.59,RD=0.02,P=0.002),骨质疏松症(RR=1.53,RD=0.07,P=0.005),肌痛(RR=1.26,RD=0.04,P=0.02),AEs治疗中断(RR=1.51,RD=0.06,P=0.0009)[144]有关。

AI给药可能与影响生活质量的潮热和肌肉骨骼AE有关。CYP19A1的rs10046变异T/T似乎与参加TEXT试验的绝经前患者因依西美坦和卵巢功能抑制降低潮热/出汗的发生率有关,从而提高患者对AI治疗的依从性[145]。博里等人发现体重指数较高的BC患者(P=0.001)和接受来曲唑与阿那曲唑的患者(P=0.018)更有可能发生关节痛并随后停止使用AI。此外,作者发现CYP19A1 rs4775936和ESR1 rs9322336、rs2234693、rs9340799 SNPs与关节痛的发生有关(P=0.016、0.018、0.017、0.047),并且CYP19A1 rs4775936 SNP与AI 146可停药相关。在254例接受AI治疗的患者中,发现骨保护素基因中的rs2073618 SNP与更高的肌肉骨骼症状和疼痛风险相关[147]。在Niravath等人的嵌套病例对照相关研究中,在不列颠哥伦比亚省参加MA.27试验的患者中,与野生型VDR相比,VDR Fok-I变异基因型与AI治疗6个月后关节痛的发生率较低相关(P<0.0001)[148]。

Fulvestrant是第一个被批准用于治疗MBC绝经后患者的纯抗雌激素药物。Fulvestrant既是一种竞争性拮抗剂,又是一种选择性雌激素受体降解剂[149]。Fulvestrant的急性毒性较低,一些报告的AE包括注射部位反应、恶心、疼痛、头痛、虚弱和肝酶升高。一项综述分析了主要现有研究的数据,以评估Fulvestrant与其他标准内分泌药物相比,对绝经后激素敏感的局部晚期或MBC患者的疗效和安全性。显示血管舒缩毒性(RR=1.02,95%CI:0.89~1.18,3 544名女性,8项研究)、关节痛(RR=0.96,95%CI:0.86~1.09,3 244名女性,7项研究)和妇科毒性(RR=1.22,95%CI:0.94~1.57,2 848名女性,6项研究)中没有显著区别[150]。

CDK4/6抑制剂Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

目前,三种细胞周期蛋白依赖性激酶(CDK)4和6抑制剂(CDK4/6)已被批准与AI和Fulvestrant联合用于HR阳性MBC患者,它们分别是Palbociclib、Ribociclib和Abemaciclib[128,151]。主要参与CDK4/6抑制剂(又是时间依赖性CYP3A抑制剂)代谢的酶以CYP3A和SULT2A1为代表[152-154]。强烈建议不要使用强效CYP3A抑制剂(例如伊曲康唑)和强效(例如苯妥英钠、克拉霉素)或中效(例如莫达非尼、地尔硫卓)CYP3A诱导剂[152-154]。因此,对适合这些药物的BC患者的最终伴随药物进行调查至关重要,尤其是患有多种并发症和多药治疗的老年患者。除某些方面外,所有CDK4/6抑制剂的安全性都相似[155-158]。一般而言,CDK4/6抑制剂联合内分泌治疗组中最常见的AE(所有级别)为中性粒细胞减少症(65%),其次是腹泻(49%)、感染(44%)、恶心(40%)、疲劳(39%)和白细胞减少(35%)[159]。临床试验中报告的其他安全问题包括肝胆毒性(Ribociclib、Abemaciclib)、心电图QT间期延长(Ribociclib)和静脉血栓栓塞[160,161]。迄今为止,预测毒性的前瞻性因素尚未得到验证且可用于临床实践以确定哪些患者更有可能发生AE。然而,之后讨论的一些可用数据可能值得进一步调查研究。

血液学毒性

中性粒细胞减少和白细胞减少是最常见的3/4级CDK4/6相关AE。贫血或血小板减少症较少见[155−158,162,163]。由于更高的CDK4选择性,Abemaciclib的所有级别中性粒细胞减少症发生率比Palbociclib和Ribociclib低50%[164]。CDK4/6抑制剂通过减少造血干细胞分裂导致细胞周期停止,减少或中断剂量后恢复,因此与化疗诱导的相同AE相比,中性粒细胞减少症会迅速恢复[165]。在使用Palbociclib和Fulvestrant的PALOMA−-3试验中,3/4级中性粒细胞减少症通常会在一周内恢复[166]。不需要粒细胞集落刺激因子,CDK4/6抑制剂研究中报告的发热性中性粒细胞减少症显著低于化疗[156−158,162,164,167,168]。发生中性粒细胞减少症的时间通常是Palbociclib和Ribociclib首次给药后15天,以及Abemaciclib的前两个周期[155,164,166,169]。建议在治疗开始前、每个后续周期开始时以及第1和第2周期的第14天进行全血细胞计数[170]。在来自PALOMA−2(n=584)和PALOMA−3(n=442)的接受Palbociclib治疗的患者中,低基线绝对中性粒细胞计数是C1D15 3/4级中性粒细胞减少症的一个强独立危险因素。ABCB1_rs1128503 (C/C vs T/T:OR=0.57,95%CI:0.311~1.047,P=0.070)和ERCC1_rs11615 (A/A vs G/G:OR=1.75,95%CI:0.901~3.397,P=0.098) SNP被确定为非亚洲患者C1D15 3/4级中性粒细胞减少症的潜在独立危险因素,因此,药物遗传学检测可能会提供有关发生严重中性粒细胞减少症的潜在风险增加的信息[171]。莫迪等人的一项研究汇集了来自MONARCH−1、2和3的数据,证明了包含种族、东部肿瘤协作组表现状态和治疗前白细胞计数在内的临床预测工具的能力,以确定在Abemaciclib开始后具有显著不同≥3级中性粒细胞减少症风险的亚组。该工具可能有助于评估个性化风险和Abemaciclib的风险收益比[172]。

胃肠道毒性

与Abemaciclib相比,用于Palbociclib和Ribociclib的Abemaciclib的3级腹泻发生率更高。在MONARCH-1试验中,接受Abemaciclib单药治疗的患者中有90%出现腹泻(通常在治疗开始后1周内),21%的患者需要减少剂量。绝大多数发作持续时间很短(中位数:2级为7.5天,3级为4.5天)[173]。在MONARCH−2中,1级和2级腹泻发生率为73%,3级为13.4%,并且在第一个治疗周期中与MONARCH−1组一致,中位持续时间为6天,无需修改治疗70.1%的患者[168]。已确定高龄与≥3级腹泻的风险增加显著相关[年龄>70岁的HR:1.72(95%CI:1.14~2.58);P=0.009][172]。患有炎症性肠病(例如溃疡性结肠炎和慢性结肠炎)的患者也需要特别小心。

QTc延长

强烈不鼓励有发生QTc延长风险的患者使用Ribociclib治疗,因为根据其浓度,这种药物可能会导致QT间期延长。在MONALEESA−2试验中,接受Ribociclib加来曲唑治疗的患者中有3.3%经历了QTc延长至>480 ms,大部分发生在第一个周期,并且受到主动剂量中断或减少的限制[162]。由于潜在的药物相互作用,在进行对症治疗时应谨慎。在临床实践中,建议根据患者的心脏状况及其潜在的QTc延长伴随药物检查符合Ribociclib的患者,应进行基线、第1周期第14天和第2周期第1天的心电图,并仔细监测以限制该AE的发生率[174]。由于存在QT间期延长的风险,当Ribociclib与止吐药(例如静脉内昂丹司琼、多拉司琼、甲氧氯普胺、苯海拉明、氟哌啶醇)合用时应特别小心[175,176]。

结论Other Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

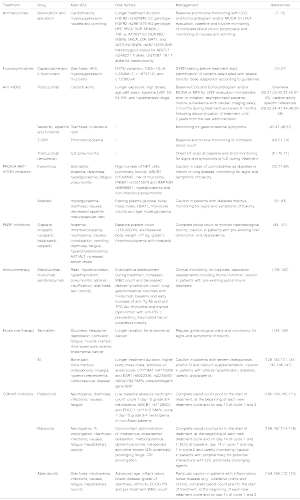

近年来,基于肿瘤生物学、遗传学和患者的临床特征,从个体化治疗的角度来看,BC的管理取得了一些进展[2]。尽管进行了深入研究,但目前还没有经过验证的前瞻性因素能够为每类BC患者确定最佳治疗方法以指导治疗选择。在精准医疗和量身定制治疗的时代,基因组测试和潜在生物标志物的识别是BC患者研究的一个不断发展的领域。在这方面,由于在日常临床实践中的潜在应用,对药物毒性特征的探索越来越有吸引力[5,6]。事实上,结合BC患者临床特征的安全性定制治疗可能对治疗选择特别有帮助(表3)。因此,了解患者的并发症和易导致特定治疗相关毒性的潜在生物标志物对于更好地选择和管理适合患者的最佳护理至关重要。目前,迫切需要将这些发现应用于临床实践以实现这一目标,但还需要进一步的研究。我们相信,如果这些因素在不久的将来和进一步的研究中得到证实,可能有助于个体化治疗,一方面,它们可以更好地选择患者;另一方面,它们将允许从个体化I和改善临床结果的角度来定制患者对毒性的监测。

Full table

AcknowledgmentsOther Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

Funding: None.

FootnoteOther Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Luca Moscetti) for the series “New Insights in Precision Oncology in Breast Cancer” published in Precision Cancer Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://pcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pcm-21-38/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://pcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pcm-21-38/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://pcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pcm-21-38/coif). The series “New Insights in Precision Oncology in Breast Cancer” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. MS reports that he has the following disclosures: consultant, advisory board and speakers’ bureau fees from Amgen, Sanofi, MSD, Eisai, Merck, Bayer. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

ReferencesOther Section

- 介绍

- 方法

- 蒽环类

- 氟嘧啶类

- 抗HER2药物

- PIK3CA−AKT−mTOR通路抑制剂

- 聚(ADP−核糖)聚合酶抑制剂(PARPi)

- 免疫疗法

- 内分泌治疗

- CDK4/6抑制剂

- 结论

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer 2021; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caswell-Jin JL, Plevritis SK, Tian L, et al. Change in Survival in Metastatic Breast Cancer with Treatment Advances: Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2018;2:pky062. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chae YK, Pan AP, Davis AA, et al. Path toward Precision Oncology: Review of Targeted Therapy Studies and Tools to Aid in Defining “Actionability” of a Molecular Lesion and Patient Management Support. Mol Cancer Ther 2017;16:2645-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brock A, Huang S. Precision Oncology: Between Vaguely Right and Precisely Wrong. Cancer Res 2017;77:6473-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown NA, Elenitoba-Johnson KSJ. Enabling Precision Oncology Through Precision Diagnostics. Annu Rev Pathol 2020;15:97-121. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernández XM. Untangling Data in Precision Oncology - A Model for Chronic Diseases? Yearb Med Inform 2020;29:184-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaitiekus D, Muckiene G, Vaitiekiene A, et al. HFE Gene Variants’ Impact on Anthracycline-Based Chemotherapy-Induced Subclinical Cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2021;21:59-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Qi H, Zhang L, et al. Effects of FGFR gene polymorphisms on response and toxicity of cyclophosphamide-epirubicin-docetaxel based chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2018;18:1038. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Todorova VK, Makhoul I, Dhakal I, et al. Polymorphic Variations Associated With Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients. Oncol Res 2017;25:1223-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schneider BP, Shen F, Gardner L, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study for Anthracycline-Induced Congestive Heart Failure. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:43-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vulsteke C, Pfeil AM, Maggen C, et al. Clinical and genetic risk factors for epirubicin-induced cardiac toxicity in early breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;152:67-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li H, Hu B, Guo Z, et al. Correlation of UGT2B7 Polymorphism with Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Epirubicin/Cyclophosphamide-Docetaxel Adjuvant Chemotherapy. Yonsei Med J 2019;60:30-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cui L, Huang J, Zhan Y, et al. Association between the genetic polymorphisms of the pharmacokinetics of anthracycline drug and myelosuppression in a patient with breast cancer with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Life Sci 2021;276:119392. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fasching PA, Kollmannsberger B, Strissel PL, et al. Polymorphisms in the novel serotonin receptor subunit gene HTR3C show different risks for acute chemotherapy-induced vomiting after anthracycline chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2008;134:1079-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuji D, Matsumoto M, Kawasaki Y, et al. Analysis of pharmacogenomic factors for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer receiving doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2021;87:73-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Froehlich TK, Amstutz U, Aebi S, et al. Clinical importance of risk variants in the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene for the prediction of early-onset fluoropyrimidine toxicity. Int J Cancer 2015;136:730-9. [PubMed]

- Diasio RB, Harris BE. Clinical pharmacology of 5-fluorouracil. Clin Pharmacokinet 1989;16:215-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson MR, Diasio RB. Importance of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) deficiency in patients exhibiting toxicity following treatment with 5-fluorouracil. Adv Enzyme Regul 2001;41:151-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meulendijks D, Henricks LM, Sonke GS, et al. Clinical relevance of DPYD variants c.1679T>G, c.1236G>A/HapB3, and c.1601G>A as predictors of severe fluoropyrimidine-associated toxicity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1639-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al. DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: a prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1459-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stavraka C, Pouptsis A, Okonta L, et al. Clinical implementation of pre-treatment DPYD genotyping in capecitabine-treated metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;175:511-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deenen MJ, Meulendijks D, Cats A, et al. Upfront Genotyping of DPYD*2A to Individualize Fluoropyrimidine Therapy: A Safety and Cost Analysis. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:227-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henricks LM, Opdam FL, Beijnen JH, et al. DPYD genotype-guided dose individualization to improve patient safety of fluoropyrimidine therapy: call for a drug label update. Ann Oncol 2017;28:2915-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lunenburg CATC, Henricks LM, Guchelaar HJ, et al. Prospective DPYD genotyping to reduce the risk of fluoropyrimidine-induced severe toxicity: Ready for prime time. Eur J Cancer 2016;54:40-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al. A cost analysis of upfront DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation in fluoropyrimidine-based anticancer therapy. Eur J Cancer 2019;107:60-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S, et al. Adjuvant Capecitabine for Breast Cancer after Preoperative Chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2147-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- EMA recommendations on DPD testing prior to treatment with fluorouracil, capecitabine, tegafur and flucytosine. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/press-release/ema-recommendations-dpd-testing-prior-treatment-fluorouracil-capecitabine-tegafur-flucytosine_en.pdf (accessed Apr 30, 2020).

- Loibl S, Gianni L. HER2-positive breast cancer. Lancet 2017;389:2415-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pondé NF, Lambertini M, de Azambuja E. Twenty years of anti-HER2 therapy-associated cardiotoxicity. ESMO Open 2016;1:e000073. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 2001;344:783-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balduzzi S, Mantarro S, Guarneri V, et al. Trastuzumab-containing regimens for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;CD006242. [PubMed]

- Mantarro S, Rossi M, Bonifazi M, et al. Risk of severe cardiotoxicity following treatment with trastuzumab: a meta-analysis of randomized and cohort studies of 29,000 women with breast cancer. Intern Emerg Med 2016;11:123-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moja L, Tagliabue L, Balduzzi S, et al. Trastuzumab containing regimens for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;CD006243. [PubMed]

- Long HD, Lin YE, Zhang JJ, et al. Risk of Congestive Heart Failure in Early Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Treatment With Trastuzumab: A Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 2016;21:547-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Azambuja E, Procter MJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Trastuzumab-associated cardiac events at 8 years of median follow-up in the Herceptin Adjuvant trial (BIG 1-01). J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2159-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Advani PP, Ballman KV, Dockter TJ, et al. Long-Term Cardiac Safety Analysis of NCCTG N9831 (Alliance) Adjuvant Trastuzumab Trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:581-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Romond EH, Jeong JH, Rastogi P, et al. Seven-year follow-up assessment of cardiac function in NSABP B-31, a randomized trial comparing doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel (ACP) with ACP plus trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3792-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bozovic-Spasojevic I, Azim HA Jr, Paesmans M, et al. Neoadjuvant anthracycline and trastuzumab for breast cancer: is concurrent treatment safe? Lancet Oncol 2011;12:209-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Russell SD, Blackwell KL, Lawrence J, et al. Independent adjudication of symptomatic heart failure with the use of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by trastuzumab adjuvant therapy: a combined review of cardiac data from the National Surgical Adjuvant breast and Bowel Project B-31 and the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3416-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swain SM, Ewer MS, Cortés J, et al. Cardiac tolerability of pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer in CLEOPATRA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. Oncologist 2013;18:257-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valachis A, Nearchou A, Polyzos NP, et al. Cardiac toxicity in breast cancer patients treated with dual HER2 blockade. Int J Cancer 2013;133:2245-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Minckwitz G, Procter M, de Azambuja E, et al. Adjuvant Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab in Early HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:122-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:25-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schneeweiss A, Chia S, Hickish T, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in combination with standard neoadjuvant anthracycline-containing and anthracycline-free chemotherapy regimens in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer: a randomized phase II cardiac safety study (TRYPHAENA). Ann Oncol 2013;24:2278-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cameron D, Casey M, Oliva C, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine in women with HER-2-positive advanced breast cancer: final survival analysis of a phase III randomized trial. Oncologist 2010;15:924-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perez EA, Koehler M, Byrne J, et al. Cardiac safety of lapatinib: pooled analysis of 3689 patients enrolled in clinical trials. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:679-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piccart-Gebhart M, Holmes E, Baselga J, et al. Adjuvant Lapatinib and Trastuzumab for Early Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive Breast Cancer: Results From the Randomized Phase III Adjuvant Lapatinib and/or Trastuzumab Treatment Optimization Trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1034-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Azambuja E, Holmes AP, Piccart-Gebhart M, et al. Lapatinib with trastuzumab for HER2-positive early breast cancer (NeoALTTO): survival outcomes of a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial and their association with pathological complete response. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1137-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1783-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Minckwitz G, Huang CS, Mano MS, et al. Trastuzumab Emtansine for Residual Invasive HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;380:617-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;382:610-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murthy RK, Loi S, Okines A, et al. Tucatinib, Trastuzumab, and Capecitabine for HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;382:597-609. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan A, Moy B, Mansi J, et al. Final Efficacy Results of Neratinib in HER2-positive Hormone Receptor-positive Early-stage Breast Cancer From the Phase III ExteNET Trial. Clin Breast Cancer 2021;21:80-91.e7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/lynparza-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761106s000lbl.pdf

- Curigliano G, Lenihan D, Fradley M, et al. Management of cardiac disease in cancer patients throughout oncological treatment: ESMO consensus recommendations. Ann Oncol 2020;31:171-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, et al. Prevention and Monitoring of Cardiac Dysfunction in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:893-911. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eschenhagen T, Force T, Ewer MS, et al. Cardiovascular side effects of cancer therapies: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dempsey N, Rosenthal A, Dabas N, et al. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: a review of clinical risk factors, pharmacologic prevention, and cardiotoxicity of other HER2-directed therapies. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021;188:21-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Upshaw JN. The Role of Biomarkers to Evaluate Cardiotoxicity. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2020;21:79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cardinale D, Colombo A, Torrisi R, et al. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: clinical and prognostic implications of troponin I evaluation. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3910-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cardinale D, Sandri MT, Martinoni A, et al. Left ventricular dysfunction predicted by early troponin I release after high-dose chemotherapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:517-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cardinale D, Sandri MT, Colombo A, et al. Prognostic value of troponin I in cardiac risk ynparza ation of cancer patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy. Circulation 2004;109:2749-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Demissei BG, Hubbard RA, Zhang L, et al. Changes in Cardiovascular Biomarkers With Breast Cancer Therapy and Associations With Cardiac Dysfunction. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e014708. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ponde N, Bradbury I, Lambertini M, et al. Cardiac biomarkers for early detection and prediction of trastuzumab and/or lapatinib-induced cardiotoxicity in patients with HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer: a NeoALTTO sub-study (BIG 1-06). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;168:631-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gavin PG, Song N, Kim SR, et al. Association of Polymorphisms in FCGR2A and FCGR3A With Degree of Trastuzumab Benefit in the Adjuvant Treatment of ERBB2/HER2–Positive Breast Cancer Analysis of the NSABP B-31 Trial. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:335-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mellor JD, Brown MP, Irving HR, et al. A critical review of the role of Fc gamma receptor polymorphisms in the response to monoclonal antibodies in cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2013;6:1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cresti N, Jamieson D, Verrill MW, et al. Fcγ-receptor Iia polymorphism and cardiotoxicity in patients with breast cancer treated with adjuvant trastuzumab. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2011. [Crossref]

- Roca L, Diéras V, Roché H, et al. Correlation of HER2, FCGR2A, and FCGR3A gene polymorphisms with trastuzumab related cardiac toxicity and efficacy in a subgroup of patients from UNICANCERPACS04 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;139:789-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/enhertu-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/761139s011lbl.pdf

- André F, O'Regan R, Ozguroglu M, et al. Everolimus for women with trastuzumab-resistant, HER2-positive, advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:580-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Awada A, Colomer R, Inoue K, et al. Neratinib Plus Paclitaxel vs. Trastuzumab Plus Paclitaxel in Previously Untreated Metastatic ERBB2-Positive Breast Cancer: The NEfERT-T Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1557-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swain SM, Miles D, Kim SB, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA): end-of-study results from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:519-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/kadcyla-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Raphael J, Lefebvre C, Allan A, et al. Everolimus in Advanced Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Target Oncol 2020;15:723-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:520-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hurvitz SA, Andre F, Jiang Z, et al. Combination of everolimus with trastuzumab plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for patients with HER2 positive advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-1): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:816-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bachelot T, Bourgier C, Cropet C, et al. Randomized phase II trial of everolimus in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer with prior exposure to aromatase inhibitors: a GINECO study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2718-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kornblum N, Zhao F, Manola J, et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Fulvestrant Plus Everolimus or Placebo in Postmenopausal Women With Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer Resistant to Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy: Results of PrE0102. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1556-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yardley DA, Bosserman LD, O’Shaughnessy JA, et al. Paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and everolimus/placebo as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic HER2-negative breast cancer: a randomized placebo controlled phase II trial of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015;154:89-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmid P, Zaiss M, Harper-Wynne C, et al. Fulvestrant plus vistusertib vs. fulvestrant plus everolimus vs. fulvestrant alone for women with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: the manta phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:1556-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Decker T, Marschner N, Muendlein A, et al. VicTORia: a randomised phase II study to compare vinorelbine in combination with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus versus vinorelbine monotherapy for second-line chemotherapy in advanced HER2-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;176:637-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Im YH, Karabulut B, Lee KS, et al. Safety and efficacy of everolimus (EVE) plus exemestane (EXE) in postmenopausal women with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: final results from EVEREXES. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021;188:77-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cazzaniga ME, Airoldi M, Arcangeli V, et al. Efficacy and safety of Everolimus and Exemestane in hormone-receptor positive (HR+) human-epidermal-growth-factor negative (HER2-) advanced breast cancer patients: New insights beyond clinical trials. The EVA study. Breast 2017;35:115-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Xie Y, Gong C, et al. Comparative Treatment Patterns and Outcomes of Fulvestrant versus Everolimus Plus Exemestane for Postmenopausal Metastatic Breast Cancer Resistant to Aromatase Inhibitors in Real-World Experience. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2020;16:607-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cazzaniga ME, Danesi R, Girmenia C, et al. Management of toxicities associated with targeted therapies for HR-positive metastatic breast cancer: a multidisciplinary approach is the key to success. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;176:483-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Willemsen AECAB, He X, van Cranenbroek B, et al. Baseline effector cells predict response and NKT cells predict pulmonary toxicity in advanced breast cancer patients treated with everolimus and exemestane. Int Immunopharmacol 2021;93:107404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pascual T, Apellániz-Ruiz M, Pernaut C, et al. Polymorphisms associated with everolimus pharmacokinetics, toxicity and survival in metastatic breast cancer. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180192. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armaghani AJ, Han HS. Alpelisib in the Treatment of Breast Cancer: A Short Review on the Emerging Clinical Data. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2020;12:251-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- André F, Ciruelos E, Rubovszky G, et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-Mutated, Hormone Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1929-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mayer IA, Prat A, Egle D, et al. A Phase II Randomized Study of Neoadjuvant Letrozole Plus Alpelisib for Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Breast Cancer (NEO-ORB). Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:2975-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodon J, Demanse D, Rugo HS, et al. A risk analysis of alpelisib (ALP)-induced hyperglycemia (HG) using baseline factors in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumours and breast cancer (BC): A pooled analysis of X2101 and SOLAR-1. Ann Oncol 2021;32:S64. [Crossref]

- Patel M, Nowsheen S, Maraboyina S, et al. The role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors in the treatment of cancer and methods to overcome resistance: a review. Cell Biosci 2020;10:35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LaFargue CJ, Dal Molin GZ, Sood AK, et al. Exploring and comparing adverse events between PARP inhibitors. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:e15-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;390:1949-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2154-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1274-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clovis Oncology. Full prescribing information for rubraca (rucaparib) 2021. Available online: https://clovisoncology.com/pdfs/RubracaUSPI.pdf (accessed Jan 8, 2018).

- AstraZeneca. Full prescribing information for Lynparza (ynparza). Available online: https://medicalinformation.astrazeneca-us.com/home/prescribing-information/lynparza-tablets-pi.html (accessed Jan 8, 2018).

- Tesaro. Full prescribing information for Zejula (niraparib). Available online: https://gskpro.com/content/dam/global/hcpportal/en_US/Prescribing_Information/Zejula_Capsules/pdf/ZEJULA-CAPSULES-PI-PIL.PDF

- Berek JS, Matulonis UA, Peen U, et al. Safety and dose modification for patients receiving niraparib. Ann Oncol 2018;29:1784-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gunderson CC, Matulonis U, Moore KN. Management of the toxicities of common targeted therapeutics for gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol 2018;148:591-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore KN, Monk BJ. Patient Counseling and Management of Symptoms During Olaparib Therapy for Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Oncologist 2016;21:954-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore K, Zhang ZY, Agarwal S, et al. The effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of niraparib, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2018;81:497-503. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao H, Sifakis EG, Sumida N, et al. PARP1- and CTCF-Mediated Interactions between Active and Repressed Chromatin at the Lamina Promote Oscillating Transcription. Mol Cell 2015;59:984-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lucarini L, Pini A, Gerace E, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition with HYDAMTIQ reduces allergen-induced asthma-like reaction, bronchial hyper-reactivity and airway remodelling. J Cell Mol Med 2014;18:468-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwaiblmair M, Behr W, Haeckel T, et al. Drug induced interstitial lung disease. Open Respir Med J 2012;6:63-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Emens LA. Breast Cancer Immunotherapy: Facts and Hopes. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:511-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- FDA approves atezolizumab for PD-L1 positive unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. FDA U.S. Food and Drug. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-approves-atezolizumab-pd-l1-positive-unresectable-locally-advanced-or-metastatic-triple-negative

- Schmid P, Rugo HS, Adams S, et al. Atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel as first-line treatment for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (Impassion130): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:44-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mittendorf EA, Zhang H, Barrios CH, et al. Neoadjuvant atezolizumab in combination with sequential nab-paclitaxel and anthracycline-based chemotherapy versus placebo and chemotherapy in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (IMpassion031): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;396:1090-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmid P, Cortes J, Pusztai L, et al. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;382:810-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barroso-Sousa R, Tolaney SM. Pembrolizumab in the preoperative setting of triple-negative breast cancer: safety and efficacy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2020;20:923-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loibl S, Untch M, Burchardi N, et al. A randomised phase II study investigating durvalumab in addition to an anthracycline taxane-based neoadjuvant therapy in early triple-negative breast cancer: clinical results and biomarker analysis of GeparNuevo study. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1279-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Voorwerk L, Slagter M, Horlings HM, et al. Immune induction strategies in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer to enhance the sensitivity to PD-1 blockade: the TONIC trial. Nat Med 2019;25:920-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krishnan T, Tomita Y, Roberts-Thomson R. A retrospective analysis of eosinophilia as a predictive marker of response and toxicity to cancer immunotherapy. Future Sci OA 2020;6:FSO608. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, Otsuka A, et al. Fluctuations in routine blood count might signal severe immunerelated adverse events in melanoma patients treated with nivolumab. J Dermatol Sci 2017;88:225-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi T, Iwama S, Yasuda Y, et al. Patients With Antithyroid Antibodies Are Prone To Develop Destructive Thyroiditis by Nivolumab: A Prospective Study. J Endocr Soc 2018;2:241-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toi Y, Sugawara S, Sugisaka J, et al. Profiling Preexisting Antibodies in Patients Treated With Anti-PD-1 Therapy for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:376-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kurimoto C, Inaba H, Ariyasu H, et al. Predictive and sensitive biomarkers for thyroid dysfunctions during treatment with immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Sci 2020;111:1468-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu Y, Fu Y, Zhu B, et al. Predictive Biomarkers of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors-Related Toxicities. Front Immunol 2020;11:2023. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang G, Nowsheen S, Aziz K, et al. Toxicity and adverse effects of Tamoxifen and other anti-estrogen drugs. Pharmacol Ther 2013;139:392-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Osborne CK. Tamoxifen in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1609-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mandalà M, Ferretti G, Cremonesi M, et al. Venous thromboembolism and cancer: new issues for an old topic. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2003;48:65-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deitcher SR, Gomes MPV. The risk of venous thromboembolic disease associated with adjuvant hormone therapy for breast carcinoma. Cancer 2004;101:439-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hirsimäki P, Aaltonen A, Mäntylä E. Toxicity of antiestrogens. Breast J 2002;8:92-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies C, Pan H, Godwin J, et al. Long-term effects of continuining adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet 2013;381:805-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dean L. Tamoxifen Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype. 2014 Oct 7 [updated 2019 May 1]. In: Pratt VM, Scott SA, Pirmohamed M, et al. editors. Medical Genetics Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US), 2012.

- Francis PA, Regan MM, Fleming GF, et al. Adjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:436-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al. Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:107-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee HR, Kim TH, Choi KC. Functions and physiological roles of two types of estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, identified by estrogen receptor knockout mouse. Lab Anim Res 2012;28:71-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barrett-Connor E. Sex differences in coronary heart disease. Why are women so superior? The 1995 Ancel Keys Lecture. Circulation 1997;95:252-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalin MF, Zumoff B. Sex hormones and coronary disease: a review of the clinical studies. Steroids 1990;55:330-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite RS, Chlebowski RT, Lau J, et al. Meta-analysis of vascular and neoplastic events associated with tamoxifen. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:937-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amir E, Seruga B, Niraula S, et al. Toxicity of adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1299-309. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coates AS, Keshaviah A, Thürlimann B, et al. Five years of letrozole compared with tamoxifen as initial adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: update of study BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:486-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van de Velde CJ, Rea D, Seynaeve C, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen and exemestane in early breast cancer (TEAM): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;377:321-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Sullivan L, et al. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1867-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1793-802. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mamounas EP, Jeong JH, Wickerham DL, et al. Benefit from exemestane as extended adjuvant therapy after 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen: intention-to-treat analysis of the National Breast Cancer Research and Treatment Surgical Adjuvant Breast And Bowel Project B-33 trial. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1965-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gray RG, Rea D, Handley K, et al. aTTom: long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years in 6,953 women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:18. [Crossref]

- The Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Lancet 2015;386:1341-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qian X, Li Z, Ruan G, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of extended aromatase inhibitors after adjuvant aromatase inhibitors-containing therapy for hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer: a literature-based meta-analysis of randomized trials. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020;179:275-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johansson H, Gray KP, Pagani O, et al. Impact of CYP19A1 and ESR1 variants on early-onset side effects during combined endocrine therapy in the TEXT trial. Breast Cancer Res 2016;18:110. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borrie AE, Rose FA, Choi YH, et al. Genetic and clinical predictors of arthralgia during letrozole or anastrozole therapy in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020;183:365-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lintermans A, Van Asten K, Jongen L, et al. Genetic variant in the osteoprotegerin gene is associated with aromatase inhibitor-related musculoskeletal toxicity in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 2016;56:31-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niravath P, Chen B, Chapman JW, et al. Vitamin D Levels, Vitamin D Receptor Polymorphisms, and Inflammatory Cytokines in Aromatase Inhibitor-Induced Arthralgias: An Analysis of CCTG MA.27. Clin Breast Cancer 2018;18:78-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fan M, Rickert EL, Chen L, et al. Characterization of molecular and structural determinants of selective estrogen receptor downregulators. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;103:37-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee CI, Goodwin A, Wilcken N. Fulvestrant for hormone-sensitive metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1:CD011093. [PubMed]

- Spring LM, Wander SA, Andre F, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: past, present, and future. Lancet 2020;395:817-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- KISQUALI. Prescribing information: ribociclib. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Available online: https://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/sites/www.pharma.us.novartis.com/files/kisqali.pdf (March 2017).

- VERZENIO. Prescribing information: abemaciclib. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company. Available online: http://pi.lilly.com/us/verzenio-uspi.pdf (September 2017).

- Dhillon S. Palbociclib: first global approval. Drugs 2015;75:543-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Infante JR, Cassier PA, Gerecitano JF, et al. A Phase I Study of the Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitor Ribociclib (LEE011) in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors and Lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:5696-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:25-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finn RS, Martin M, Rugo HS, et al. Palbociclib and Letrozole in Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1925-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cristofanilli M, Turner NC, Bondarenko I, et al. Fulvestrant plus palbociclib versus fulvestrant plus placebo for treatment of hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer that progressed on previous endocrine therapy (PALOMA-3): final analysis of the multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:425-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ding W, Li Z, Wang C, et al. The CDK4/6 inhibitor in HR-positive advanced breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e10746. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abemaciclib summary of product characteristics. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/208855s000lbl.pdf (Accessed 31 Aug 2018).

- Ribociclib summary of product characteristics. Available online: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/004213/WC500233997.pdf (Accessed 31 Aug2018).

- Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, et al. Ribociclib as First-Line Therapy for HR-Positive, Advanced Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1738-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DeMichele A, Clark AS, Tan KS, et al. CDK 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib (PD0332991) in Rb+ advanced breast cancer: phase II activity, safety, and predictive biomarker assessment. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:995-1001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goetz MP, Toi M, Campone M, et al. MONARCH 3: Abemaciclib As Initial Therapy for Advanced Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3638-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu W, Sung T, Jessen BA, et al. Mechanistic Investigation of Bone Marrow Suppression Associated with Palbociclib and its Differentiation from Cytotoxic Chemotherapies. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:2000-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verma S, Bartlett CH, Schnell P, et al. Palbociclib in Combination With Fulvestrant in Women With Hormone Receptor-Positive/HER2-Negative Advanced Metastatic Breast Cancer: Detailed Safety Analysis From a Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase III Study (PALOMA-3). Oncologist 2016;21:1165-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tripathy D, Sohn J, Im SA, et al. First-line ribociclib vs. placebo with goserelin and tamoxifen or a non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor in premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer: Results from the randomized phase III MONALEESA-7 trial. Cancer Res 2018;4:GS2-05.

- Sledge GW Jr, Toi M, Neven P, et al. MONARCH 2: Abemaciclib in Combination With Fulvestrant in Women With HR+/HER2- Advanced Breast Cancer Who Had Progressed While Receiving Endocrine Therapy. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2875-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- IBRANCE. Prescribing information: palbociclib. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc, Available online: http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspX?id=2191 (March 2017).

- Rugo HS, Diéras V, Gelmon KA, et al. Impact of palbociclib plus letrozole on patient-reported health-related quality of life: results from the PALOMA-2 trial. Ann Oncol 2018;29:888-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iwata H, Umeyama Y, Liu Y, et al. Evaluation of the Association of Polymorphisms With Palbociclib-Induced Neutropenia: Pharmacogenetic Analysis of PALOMA-2/-3. Oncologist 2021;26:e1143-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Modi ND, Abuhelwa AY, Badaoui S, et al. Prediction of severe neutropenia and diarrhoea in breast cancer patients treated with abemaciclib. Breast 2021;58:57-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dickler MN, Tolaney SM, Rugo HS, et al. MONARCH 1, A Phase II Study of Abemaciclib, a CDK4 and CDK6 Inhibitor, as a Single Agent, in Patients with Refractory HR+/HER2- Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:5218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thill M, Schmidt M. Management of adverse events during cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitor-based treatment in breast cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2018;10:1758835918793326. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barni S, Petrelli F, Cabiddu M. Cardiotoxicity of antiemetic drugs in oncology: An overview of the current state of the art. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016;102:125-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olasińska-Wiśniewska A, Olasiński J, Grajek S. Cardiovascular safety of antihistamines. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2014;31:182-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

董嘉

复旦大学附属肿瘤医院(更新时间:2023-05-05)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Lai E, Persano M, Dubois M, Spanu D, Donisi C, Pozzari M, Deias G, Saba G, Migliari M, Liscia N, Dessì M, Scartozzi M, Atzori F. Drug-related toxicity in breast cancer patients: a new path towards tailored treatment?—a narrative review. Precis Cancer Med 2022;5:15.