关于BRCA突变在泌尿生殖系统和妇科肿瘤中最新研究的系统性综述

介绍

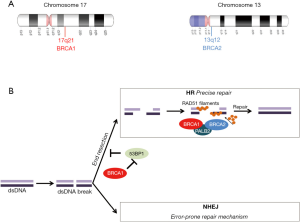

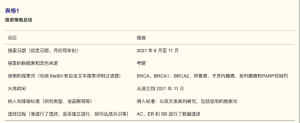

乳腺癌抑癌基因1(BRCA1、17q21、113705OMIM)和2(BRCA2、13q12.3、600185OMIM)(图1A)的突变与特定类型上皮恶性肿瘤的风险显著增加有关[1]。这两个基因都以常染色体显性遗传方式遗传,它们编码的蛋白质是同源重组(HR)修复途径的一部分(图1B),并且积极参与DNA损伤修复(DDR)过程[2-4]。因此,功能性BRCA1和BRCA2蛋白在修复双链DNA断裂中起着至关重要的作用[5]。现已发现遗传因素(BRCA1和BRCA2突变)约占所有乳腺癌的5%~10%[6]。在遗传性乳腺癌中,BRCA1和BRCA2的胚系突变约占所有病例的30%,它们主要与早发性乳腺癌、双侧乳腺癌、三阴性(ER、PR和HER2阴性)乳腺癌相关,这类疾病的主要特征是有明显的乳腺癌家族史[7,8]。除了乳腺癌和卵巢癌,BRCA1和BRCA2基因突变也与子宫管癌和腹膜癌患病风险增加有关,而BRCA2突变与男性乳腺癌以及胰腺癌、PC和黑色素瘤的风险增加有关[9]。所有与BRCA突变相关的癌症都是“遗传性乳腺癌和卵巢癌”(HBOC)综合征的一部分[9,10]。据报道,HBOC患者患有其他类型肿瘤的风险也会增加,例如PC、胃癌、胰腺癌和黑色素瘤[11]。

在这篇综述中,我们试图对有关BRCA突变的卵巢癌、前列腺癌和子宫内膜癌(EC)的文献进行全面回顾,同时强调BRCA突变在泌尿生殖系统和妇科癌症中的患病率和预后作用。我们还概述了PARP抑制剂在上述泌尿生殖系统和妇科癌症中的治疗意义和有效作用。作者的Narrative Review报告清单(可在https://pcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pcm-21-47/rc获得)。

方法

在PubMed中使用以下术语进行了系统的文献检索:BRCA、BRCA1和BRCA2、卵巢癌、子宫内膜癌、前列腺癌、PARP抑制剂。仅涉及英语文章(表1)。

Full table

卵巢癌和BRCA

卵巢癌(OC)在全球范围女性最常见癌症中位于第八位,迄今为止约75%~80%的患者在诊断时已处于卵巢癌晚期[12,13]。它是第二大最常见的妇科恶性肿瘤,全世界每年约有225 000名女性发病[14]。

在过去的二十年里,晚期卵巢癌的护理标准是结合细胞减灭术和全身性铂类化疗。然而不幸的是,大多数晚期疾病患者在治疗后3年内复发的风险很高[15]。大多数卵巢癌是常染色体显性遗传癌症易感性综合征HBOC的一部分,该综合征易患乳腺癌和卵巢癌。HBOC综合征源于主要在BRCA1或BRCA2中的胚系突变[11]。携带BRCA1或BRCA2突变的杂合子的人增加了发生卵巢癌的风险,BRCA1突变发生卵巢癌的可能性为40%~60%,BRCA2突变发生卵巢癌可能性为11%~30%[16,17]。据报告BRCA基因的胚系突变已存在在OC的多种组织学亚型,包括子宫内膜样、透明细胞,其中在高级别浆液性卵巢癌中的突变率最高[18-21]。卵巢癌中BRCA1/2突变的发生率在10%~25%之间变化,发生率具体取决于OC亚型[22-25]。与没有胚系突变的患者相比,在高级别浆液性卵巢癌患者中存在胚系BRCA突变可为患者带来生存收益[26]。特别是BRCA2突变携带者具有更高的存活率,这是由于BRCA2蛋白在调节交联损伤修复过程中的作用导致的[27]。

过去十年里的组织学、分子和遗传学证据表明,大多数输卵管癌和原发性腹膜癌应被视为一个单一的实体,并与OC使用相似的治疗方式[28]。2014年,FIGO妇科肿瘤委员会对卵巢癌分期的修订将卵巢癌、输卵管癌和腹膜癌纳入同一系统[29]。通常这3个癌种都在同样的PARP抑制剂试验中,然而最近的SEER分析显示,不同肿瘤的治疗时机、不同治疗效果也不相同[30]。由于回顾性研究方法和注册分析的固有局限性,不能过度解释该研究的结果。按肿瘤亚群对Ⅲ期随机对照试验的亚组分析将更加清楚PARP抑制剂的不同作用。

目前已确定BRCA相关OC表现出独特的临床特征,早期诊断提高了生存率以及对特定化学疗法和其他治疗有更高的反应性(详细情况在本篇综述“靶向BRCA突变的癌症”部分进行叙述)[13,31]

子宫内膜癌和BRCA

在发达国家最常见的女性癌症中,EC排在第五位[32]。EC可分为两种组织学类型,这两种类型的发病率和预后不同:Ⅰ型包括预后相对较好的低级别肿瘤大约占总患者的80%;Ⅱ型包括预后相对较差的高级别子宫内膜瘤约占总患者的20%[32,33]。据报道多种风险因素与EC发生有关,包括非遗传因素(暴露于雌激素、初潮早发、绝经晚发、肥胖等);遗传因素在几个家族性病例中被报告出来[34,35]。

遗传性EC是Lynch综合征、Cowden综合征和HBOC综合征3种不同综合征的一部分[35-37]。Lynch综合征主要是由DNA错配修复基因MutLHomolog1(MLH1)、MutSHomolog2(MSH2)、MutSHomolog6(MSH6)和PMS1Homolog2(PMS2)显性突变导致的。携带一种MMR基因胚系突变的患者,尤其是携带MSH2或MLH1突变的女性人群,一生中罹患EC的累积风险有20%~70%[36-38]。肿瘤抑制基因磷酸酶和张力蛋白同源物(PTEN)的突变导致的Cowden综合征是一种罕见病,其特征是在多个器官中发生肿瘤,并且增加患者患EC的风险[35]。虽然HBOC患者更有可能发生EC,但将EC分类为HBOC的一部分仍然存在争议,尽管有新的证据支持EC作为BRCA相关HBOC综合征的一部分,但临床结果不佳[39],这可能对EC患者的治疗策略和临床管理有重要影响。

在大多数报告的具有胚系BRCA突变的EC的数据中,按年龄、种族或EC亚型评估EC的发病率显示BRCA突变携带者(以BRCA1突变为主)患EC风险略有增加。2019年,一项涉及11,000多名BRCA1突变携带者的多国队列研究清楚地概述了BRCA1突变与EC风险之间的相关性[40]。这是最早将BRCA突变与EC发病风险联系起来的报告。有研究进一步报告了携带BRCA1和BRCA2突变的女性犹太人有更高的概率患乳头状浆液性子宫癌[41-43]。另一项研究报告称他莫昔芬暴露是BRCA突变携带者患EC风险增加的主要原因[44]。在另一项前瞻性研究中,这些数据在较小程度上得到了进一步证实[45]。另一方面,有研究质疑BRCA突变与发生EC的风险之间的相关性[46,47],该项包含1,170例EC患者的大型队列研究表明,胚系BRCA1/2突变的发生率在Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型EC以及子宫浆液性癌中发生率较低[48]。最近一项Meta分析报告评估了BRCA1或BRCA2胚系突变携带者患EC风险,该报告表明BRCA1/2突变携带者EC的患病率为0.59%[49]。该研究表明BRCA1突变携带者的EC患病率为0.62%,BRCA2突变携带者为0.47%[49]。

前列腺癌和BRCA

PC是全球男性第二常见肿瘤[50]。尽管PC的治疗已有长足的进展,但转移性去势抵抗性前列腺癌(mCRPC)患者的临床结果很差,中位生存期(OS)仍不理想[51]。PC被列为最具遗传性的人类癌症之一,大部分mCRPC患者携带潜在的可控的胚系和体细胞遗传变异,其中最常见的是BRCA2突变[52-55]。

分子学研究表明,mCRPC和局限性PC之间的基因概貌和模式不同[53,56,57]。据报道,男性转移性PC的DDR基因胚系突变的发生率介于11%~33%之间,显著高于男性局限性PC的概率[56,57]。在DDR缺陷基因中BRCA2的突变频率最高,其次是突变频率较低的ATM、TP53、CDL12、CHEK2、BRCA1、FANCA、RAD51、MLH1等基因[56-58]。一项大型研究调查了692例转移性PC的患者,BRCA2突变的发生率为5.3%,BRCA1突变的发生率为0.9%[57]。多项回顾性研究表明,BRCA2突变与PC发生风险之间存在密切关联,与一般男性相比PC患病风险升高了2~6倍;而BRCA1突变与年轻时患PC的中等风险有密切关系[59-64]。BRCA2突变被认为是mCRPC患者的强独立负性预后因素,并与短无转移生存率和癌症特异性生存率相关[65,66]。不仅如此,BRCA突变通常在疾病晚期(T3/T4)被诊断出来,并且该突变与淋巴结受累和转移有关[65]。

多项回顾性研究中报告的结果相互矛盾,所以并不能明确BRCA2突变是否会影响接受标准治疗的mCRPC患者的临床结局[67-69]。报告表明一线治疗方案的选择可能是影响胚系突变BRCA2患者预后的主要因素[70]。PC是一种临床异质性疾病,不同患者对治疗的反应不同导致不同的治疗结果,出现这种情况可能是因为PC细胞的分子异质性。因此,分子分析会有很大的好处,通过检测BRCA突变来预测患者对聚ADP核糖聚合酶(PARP)抑制剂和铂类药物等治疗方式的反应。PC中BRCA突变具体的治疗意义将在下一节详细介绍。

靶向BRCA突变的癌症

在乳腺癌和其他癌症的治疗选择中,BRCA1/2突变是一种有重要作用的生物标志物。BRCA突变个体中出现的肿瘤具有同源修复缺陷(HRD)(图1B)[5],这种缺陷可能导致细胞对铂类化疗和PARP抑制剂治疗敏感。2005年,两个独立研究小组报告,BRCA缺陷型癌症对PARP抑制敏感,揭示了PARP抑制和BRCA突变之间发生的合成致死相互作用过程[71,72]。

含铂化疗

铂类治疗癌症是基于其干扰DNA修复机制的能力,该机制引起多种癌症细胞发生DNA损伤和凋亡。一旦DNA修复机制发生改变,肿瘤细胞对含铂化疗的应答就会进一步增强[73]。这些细胞毒性药物通过DNA损伤、DNA合成和有丝分裂抑制杀死癌细胞,同时还能诱导细胞凋亡[73]。

铂类抗癌药物已在许多临床试验中得到广泛探索,目前主要应用于单药治疗或与其他化疗药物联合治疗mCRPC与激素敏感疾病[74,75]。与非BRCA相关的OC相比,具有胚系突变BRCA1或BRCA2的OC对铂基治疗具有更高的敏感性以及较高的OS。尽管开始治疗时对铂类和紫杉烷类一线化疗的反应性好,但大多数OC患者仍会复发,中位无进展生存期(PFS)为18个月[76]。

对铂类化疗的敏感性大幅下降后可导致疾病复发、对铂类药物产生耐药性,随后出现铂类难治性疾病,以铂类治疗开始后6个月内疾病进展为特征,通常预后非常差[77]。

PARP抑制剂

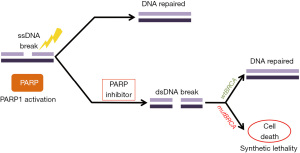

PARP抑制剂作用机制基于BRCA缺陷肿瘤的合成致死性原理,因为肿瘤细胞无法修复断裂的双链DNA从而导致死亡(图2)[78]。在正常细胞中,PARP家族酶通过HR、碱基切除修复(BER)或核苷酸切除修复(NER)机制修复单链断裂的DNA损伤[79]。合成致死性概念是指两个基因中的任何一个单独突变没有严重影响,但联合突变会导致细胞死亡,这一概念在BRCA1或BRCA2突变细胞系中得到证实[71,72]。PARP抑制和BRCA功能丧失之间的合成致死相互作用的机制被认为与单链断裂的累积有关,单链断裂会阻断复制叉并导致双链断裂[5,78]。正常细胞具有稳定的修复双链断裂的潜能力,然而有HRD的癌细胞无法做到这一点。人们认为在具有非功能性BRCA的癌细胞中双链断裂累积导致基因组损伤和不稳定性,最终导致细胞死亡[5,78,80]。

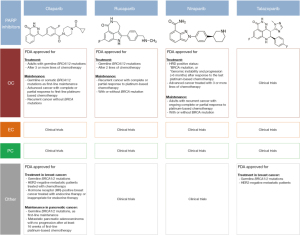

在奥拉帕尼的Ⅰ期研究(NCT00516373)中首次探索了该途径的治疗抑制剂,该项研究结果于2009年发表该研究表明,奥拉帕利在BRCA突变的癌症中具有抗肿瘤活性,与常规化疗相比其不良反应较少[31]。2014年,欧洲药品管理局(EMA)批准奥拉帕利用于携带BRCA突变的复发性高级别浆液性上皮性卵巢癌、输卵管癌或原发性腹膜癌患者的维持治疗[81]。几个月后,美国食品药品监督管理局(FDA)批准奥拉帕利用于上述相同的癌症,用于先前接受3种或更多化疗的胚系BRCA突变患者[82]。最近,一项为期5年的Ⅲ期随访(NCT01844986)试验报告,奥拉帕利维持治疗2年的益处持续到治疗结束后,中位PFS延长至56个月[83]。

在奥拉帕利获得批准后(NCT01874353),2016年~2017年间的两项随机Ⅲ期临床试验报告了PFS的显著改善,这使得鲁卡帕利和尼拉帕利(NCT01847274和NCT01968213)获批用于完全或部分铂敏感性复发性BRCA突变卵巢癌的维持治疗[84-86]。FDA和EMA分别于2016年和2018年批准鲁卡帕利用于发生胚系或体细胞BRCA突变的高分化浆液性上皮性卵巢癌、输卵管癌或原发性腹膜癌的二线及二线以上化疗后的治疗[87-89]。2017年,FDA和EMA批准尼拉帕利作为复发性上皮性卵巢癌、输卵管癌或原发性腹膜癌患者铂类药物治疗后获得完全或部分缓解患者的维持治疗。在新诊断晚期OC且对铂类化疗有良好反应的患者中,无论是否存在HRD,尼拉帕利治疗均显示出更长的PFS[90]。这就表明对铂治疗抵抗降低了对PARP抑制的敏感性;然而,另一项研究显示铂类耐药疾病患者具有显著的抗肿瘤作用[31,91]。

对于治疗前复发性卵巢癌来说维持治疗也是诱导治疗[82,88,92]。临床试验进一步证明,即使在没有胚系BRCA突变的情况下,PARP抑制剂在OC中也具有显著的临床活性[81,93]。一项Ⅱ期临床研究(NCT00679783)中首次报道使用奥拉帕利治疗OC和未知BRCA状态、BRCA阴性或BRCA阳性的患者[93]。随后FDA和EMA批准无论BRCA突变状态如何均使用奥拉帕利作为铂敏感复发性OC的维持治疗[81,86]。

目前,奥拉帕利、尼普拉帕利、鲁卡帕利和他拉唑帕利正在作为单一疗法或标准治疗组合新疗法在不同的环境和不同疾病阶段进行临床试验。例如,在铂敏感并且复发生殖系未突变BRCA的卵巢癌(NCT03402841)患者中使用奥拉帕利做维持性单一疗法;在新诊断OC患者中使用尼拉帕利做维持治疗(NCT04986371);在OC患者中卡铂一线化疗贝伐单抗维持治疗后,鲁卡帕利作为维持治疗(NCT04227522);他拉唑帕尼和放射疗法治疗局部复发的妇科癌症患者(NCT03968406)以及许多其他临床试验。

在PC中,一些PARP抑制剂仍在研究中,尤其是在mCRPC患者中的研究。在人类PC细胞系(DU145)中进行的研究证实了已知的奥拉帕利在PC细胞中的情况,证实了PARP1和PARP2的捕获,并为进一步研究提供了理论基础[94]。奥拉帕利是第一种在mCRPC患者中表现出显著活性的PARP抑制剂。在一项Ⅱ期临床试验中,88%的DDR患者对奥拉帕利表现出良好的反应,并提高了放射学PFS和OS[56]。为了评估PARP抑制剂在mCRPC中的作用和功效[70],许多Ⅰ期、Ⅱ期或Ⅲ期临床试验正在进行奥拉帕利、尼帕利、鲁卡帕利和他拉帕利的测试(NCT03874884、NCT02861573、NCT03787680、NCT03332820、NCT03834519、NCT03431350、NCT037048641、NCT038740200、NCT02975934、NCT04019327、NCT033395197)。

在EC中,临床前试验确实报告了PTEN缺陷细胞对PARPi的敏感性;然而目前为止,没有临床证据表明PTEN改变的肿瘤有活性。体外研究的数据表明,PTEN缺乏对PARP抑制剂(KU0058948或奥拉帕利)具有更高的敏感性[95-96]。PTEN缺陷型EC细胞对奥拉帕利和他拉帕利比野生型PTEN细胞系更敏感。由于PTEN突变细胞中PI3K/mTOR通路过度激活,所以同时使用PI3K抑制剂增强这些细胞对PARP抑制剂的敏感性[97]。此外,在小鼠身上进行的体内研究表明,PARP抑制剂与激素治疗结合可提高PTEN缺陷型EC的抗肿瘤疗效[98]。两个不同的病例报告了奥拉帕利用于EC治疗,第一例患者有复发性EC(PTEN缺陷,体细胞BRCA1/2阴性)并伴有脑转移,对奥拉帕尼反应良好。但是她在开始治疗后8个月出现了疾病进展[99]。第二例为复发的低分化EC(胚系BRCA2突变),在接受奥拉帕利作为维持治疗后,治疗效果良好并且无进展生存期超过15个月[100]。目前许多Ⅰ期和Ⅱ期临床试验在评估奥拉帕利、尼普拉帕利、鲁卡帕利和他拉帕利单药治疗或与其他疗法结合治疗复发、晚期和转移性EC的作用和疗效(NCT03745950、NCT03951415、NCT02755844、NCT04065269、NCT03617679、NCT03794262、NCT33552471、NCT040180284、NCT03016338、NCT02127151、NCT03968406和其他疗法)。

一些临床试验表明,PARP抑制剂在治疗其他癌症(HER2阴性BRCA突变乳腺癌和胰腺癌)时具有显著的益处和预后改善[82,101-102]。事实上,2018年,FDA批准奥拉帕利和他拉帕利用于治疗化疗后复发的HER2阴性BRCA突变的转移性乳腺癌患者[101-102]。迄今为止,关于使用他拉唑帕利治疗OC的数据不足。很少一部分的Ⅰ期临床试验(NCT01286987)对这一问题进行探究[103-104],而其他相关研究仍在进行中(NCT02316834、NCT02326844)。为比较他拉唑帕利与已批准的PARP抑制剂在OC中的作用还需要进一步的研究和临床试验。

PARP抑制剂联合其他治疗

有几项探索PARP抑制剂与其他疗法结合的研究报告了DNA潜在的损伤增加,这使进一步的抗肿瘤作用成为可能。人们正在研究多种治疗药物与PARP抑制剂联合使用用于治疗,包括血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)抑制剂和PD−1/PD_L1、抗CTLA4单克隆抗体、mTOR抑制剂、AKT抑制剂和PI3K抑制剂,以及MEK1/2和WEE1抑制剂[105]。目前正在进行的临床试验多是评估PARP抑制剂与其他治疗剂的联合作用。例如,联合PARP抑制剂和免疫检查点策略可诱导重要且有效的毒性水平。另一方面,奥拉帕利与杜鲁单抗(抗PD−L1)或尼拉帕利联合培溴利珠单抗(抗PD−1)显示出与单一治疗策略类似的理想的抗肿瘤活性和安全性[106-108]。将PARP抑制剂与抗血管生成药物如奥拉帕利和赛迪拉尼(VEGF的有效抑制剂)联合使用,与单独使用奥拉帕尼相比,结果显示有显著更长的PFS[109]。

综上所述,在FDA批准的4种PARP抑制剂中(图3),到目前为止,只有奥拉帕利、鲁卡帕利和尼拉帕利3种药物被批准用于治疗或维持治疗OC。目前正在进行的几项临床试验多在评估获FDA批准的PARP抑制剂以及新分子作为单一疗法或联合疗法治疗泌尿生殖系统和妇科肿瘤的使用情况。

BRCAness,超越BRCA1和BRCA2突变

在过去十年中,部分散发性癌症特别是HBOC例如卵巢癌,没有BRCA突变。尽管如此,它们与BRCA突变癌症具有相似的病理和临床特征。这一概念被命名为“BRCAness”,它反映了散发性癌症和携带BRCA突变的家族性癌症之间的共同表型[110]。“BRCAness”是存在同源重组DNA修复缺陷但未检测到胚系BRCA突变[111]。观察到的HR缺陷可能由多种机制引起,例如:BRCA1启动子的高甲基化、体细胞BRCA突变或可调节HR修复的单个基因缺陷(ATM、ATR、CHEK1、CHEK2、DSS1、RAD51、NBS1、FANC基因家族)[112]。此外,EMSY扩增和PTEN突变/缺失也与HRD相关[112]。但是也有其他研究报告显示EMSY或PTEN基因与HRD表型之间的联系尚不明确[113-114]。

如今,PARP抑制剂的使用不仅局限于胚系BRCA突变的疾病,更普遍地适用于HRDOC[90,115]。这一概念在治疗与临床上都很重要。在一些关于OC的临床试验中,尽管没有BRCA突变但PARP抑制剂仍显示出药物活性[81,93]。

在肿瘤的分子分析领域取得的进展使得确定BRCANESS的能力得到了提高。但是,除了BRCA突变之外检测也存在一定的限制。检测HR修复的功能生物标志物(HRR)和对PARPI的反应[56,116],增加了我们对癌细胞的了解,并且能够验证创新的靶向疗法如PARP抑制剂的实用性。

结论和观点

近年来关于癌症基因和潜在治疗靶点之间作用机制的研究蓬勃发展,这推动了发现和开发PARP抑制剂合成致死疗法治疗BRCA突变癌症患者的发展。迄今为止,PARP抑制剂仍然是FDA批准利用合成致死性方法的唯一疗法。大规模研究已经发现了能够靶向癌细胞的其他合成致死相互作用[117],其他研究以期沿着相同的概念发现新的治疗靶点。CRISPR干扰(CRISPRi)方法或其变体技术“Perturb-Seq”等新的科学技术的出现,使得将识别基因特征、途径的新成分和基因靶标作为一种有价值的新型工具,这些工具可用于描绘大规模遗传相互作用[118,119]。总之分子和基因组领域的进展以及正在进行的临床前和临床研究,无疑将为精确医学时代新的稳健方法的发现和实施铺平道路。

BRCA突变的鉴定不仅可以帮助患者,还可以让亲属进行遗传咨询和检测。来自临床前、临床和转化研究的可用数据,使得这些正在进行的研究能够评估不同的治疗策略,例如PARP抑制剂和免疫检查点抑制剂的组合:PD−1/PD−L1抑制剂治疗OC(NCT04191135,NCT03911453);PI3K抑制剂治疗OC、PC和EC(NCT4586335)或PARP抑制剂和抗血管生成剂的联合使用(即NCT04566952)。这些正在进行的临床试验的结果为新药和新治疗组合的临床益处提供了更全面的数据[120]。

一个重要的不可忽略的因素是患者对PARP抑制剂的抗性。先前的研究表明,耐药的发生有多种不同的细胞机制,如BRCA逆转导致同源性定向DNA修复的恢复,或者是通过突变/下调导致53BP1的丢失[121,122]。检测这些生物标志物并进一步鉴定新的生物标志物将使患者能够选择PARP抑制剂。另一种方法是克服对PARP抑制剂的获得性抗性,例如通过抑制CDK12、WEE1或ATR[123-125]。随着PARP抑制剂的开发取得了成功,为了扩大临床试验范围和揭示潜在的新治疗靶点,还需要进一步研究探索克服耐药性的替代方法。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Precision Cancer Medicine for the series “Precision Oncology in Urogenital and Gynecological Tumors”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://pcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pcm-21-47/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://pcm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/pcm-21-47/coif). The series “Precision Oncology in Urogenital and Gynecological Tumors” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. ER and SB served as the unpaid Guest Editors of the series. ER serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Precision Cancer Medicine from July 2021 to June 2023. MM is currently an employee of Novartis, Basel, Switzerland. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Rosen EM, Pishvaian MJ. Targeting the BRCA1/2 tumor suppressors. Curr Drug Targets 2014;15:17-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindor NM, McMaster ML, Lindor CJ, et al. Concise handbook of familial cancer susceptibility syndromes - second edition. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2008;(38):1-93.

- Boulton SJ. Cellular functions of the BRCA tumour-suppressor proteins. Biochem Soc Trans 2006;34:633-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roy R, Chun J, Powell SN. BRCA1 and BRCA2: different roles in a common pathway of genome protection. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;12:68-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lord CJ, Ashworth A. PARP inhibitors: Synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science 2017;355:1152-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valencia OM, Samuel SE, Viscusi RK, et al. The Role of Genetic Testing in Patients With Breast Cancer: A Review. JAMA Surg 2017;152:589-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Economopoulou P, Dimitriadis G, Psyrri A. Beyond BRCA: new hereditary breast cancer susceptibility genes. Cancer Treat Rev 2015;41:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharma P, Klemp JR, Kimler BF, et al. Germline BRCA mutation evaluation in a prospective triple-negative breast cancer registry: implications for hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer syndrome testing. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014;145:707-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grignol VP, Agnese DM. Breast Cancer Genetics for the Surgeon: An Update on Causes and Testing Options. J Am Coll Surg 2016;222:906-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Pal T, et al. BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer 1993.

- Kobayashi H, Ohno S, Sasaki Y, et al. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility genes Oncol Rep 2013;30:1019-29. (review). [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banerjee S, Kaye SB. New strategies in the treatment of ovarian cancer: current clinical perspectives and future potential. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:961-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banerjee S, Kaye SB, Ashworth A. Making the best of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2010;7:508-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013;24:vi24-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT. Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet 1995;56:265-71. [PubMed]

- Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet 1998;62:676-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, et al. Prevalence and penetrance of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population series of 649 women with ovarian cancer. Am J Hum Genet 2001;68:700-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pal T, Permuth-Wey J, Betts JA, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for a large proportion of ovarian carcinoma cases. Cancer 2005;104:2807-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang S, Royer R, Li S, et al. Frequencies of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among 1,342 unselected patients with invasive ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2011;121:353-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soegaard M, Kjaer SK, Cox M, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence and clinical characteristics of a population-based series of ovarian cancer cases from Denmark. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:3761-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ledermann JA, Drew Y, Kristeleit RS. Homologous recombination deficiency and ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer 2016;60:49-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manchana T, Phoolcharoen N, Tantbirojn P. BRCA mutation in high grade epithelial ovarian cancers. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2019;29:102-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, et al. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2654-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdulrashid K, AlHussaini N, Ahmed W, et al. Prevalence of BRCA mutations among hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer patients in Arab countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2019;19:256. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rubin SC, Benjamin I, Behbakht K, et al. Clinical and pathological features of ovarian cancer in women with germ-line mutations of BRCA1. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1413-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cipak L, Watanabe N, Bessho T. The role of BRCA2 in replication-coupled DNA interstrand cross-link repair in vitro. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2006;13:729-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, et al. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2021;155:61-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prat JFIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. FIGO's staging classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: abridged republication. J Gynecol Oncol 2015;26:87-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavlidis N, Rassy E, Vermorken JB, et al. The outcome of patients with serous papillary peritoneal cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and epithelial ovarian cancer by treatment eras: 27 years data from the SEER registry. Cancer Epidemiol 2021;75:102045. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med 2009;361:123-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnatty SE, Tan YY, Buchanan DD, et al. Family history of cancer predicts endometrial cancer risk independently of Lynch Syndrome: Implications for genetic counselling. Gynecol Oncol 2017;147:381-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Felix AS, Weissfeld JL, Stone RA, et al. Factors associated with Type I and Type II endometrial cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:1851-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Win AK, Reece JC, Ryan S. Family history and risk of endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:89-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shai A, Segev Y, Narod SA. Genetics of endometrial cancer. Fam Cancer 2014;13:499-505. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ring KL, Bruegl AS, Allen BA, et al. Germline multi-gene hereditary cancer panel testing in an unselected endometrial cancer cohort. Mod Pathol 2016;29:1381-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cohen SA, Leininger A. The genetic basis of Lynch syndrome and its implications for clinical practice and risk management. Appl Clin Genet 2014;7:147-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stoffel E, Mukherjee B, Raymond VM, et al. Calculation of risk of colorectal and endometrial cancer among patients with Lynch syndrome. Gastroenterology 2009;137:1621-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Jonge MM, Ritterhouse LL, de Kroon CD, et al. Germline BRCA-Associated Endometrial Carcinoma Is a Distinct Clinicopathologic Entity. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:7517-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thompson D, Easton DFBreast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Cancer Incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:1358-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lavie O, Ben-Arie A, Segev Y, et al. BRCA germline mutations in women with uterine serous carcinoma--still a debate. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2010;20:1531-4. [PubMed]

- Biron-Shental T, Drucker L, Altaras M, et al. High incidence of BRCA1-2 germline mutations, previous breast cancer and familial cancer history in Jewish patients with uterine serous papillary carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2006;32:1097-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruchim I, Amichay K, Kidron D, et al. BRCA1/2 germline mutations in Jewish patients with uterine serous carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2010;20:1148-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beiner ME, Finch A, Rosen B, et al. The risk of endometrial cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. A prospective study. Gynecol Oncol 2007;104:7-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Segev Y, Iqbal J, Lubinski J, et al. The incidence of endometrial cancer in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: an international prospective cohort study. Gynecol Oncol 2013;130:127-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shu CA, Pike MC, Jotwani AR, et al. Uterine Cancer After Risk-Reducing Salpingo-oophorectomy Without Hysterectomy in Women With BRCA Mutations. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1434-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee YC, Milne RL, Lheureux S, et al. Risk of uterine cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Eur J Cancer 2017;84:114-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Long B, Lilyquist J, Weaver A, et al. Cancer susceptibility gene mutations in type I and II endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2019;152:20-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matanes E, Volodarsky-Perel A, Eisenberg N, et al. Endometrial Cancer in Germline BRCA Mutation Carriers: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2021;28:947-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-years for 32 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:524-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillessen S, Omlin A, Attard G, et al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: recommendations of the St Gallen Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) 2015. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1589-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mucci LA, Hjelmborg JB, Harris JR, et al. Familial Risk and Heritability of Cancer Among Twins in Nordic Countries. JAMA 2016;315:68-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell 2015;161:1215-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kote-Jarai Z, Leongamornlert D, Saunders E, et al. BRCA2 is a moderate penetrance gene contributing to young-onset prostate cancer: implications for genetic testing in prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2011;105:1230-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eeles R, Goh C, Castro E, et al. The genetic epidemiology of prostate cancer and its clinical implications. Nat Rev Urol 2014;11:18-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, et al. DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1697-708. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, et al. Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:443-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mateo J, Seed G, Bertan C, et al. Genomics of lethal prostate cancer at diagnosis and castration resistance. J Clin Invest 2020;130:1743-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oh M, Alkhushaym N, Fallatah S, et al. The association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with prostate cancer risk, frequency, and mortality: A meta-analysis. Prostate 2019;79:880-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kirchhoff T, Kauff ND, Mitra N, et al. BRCA mutations and risk of prostate cancer in Ashkenazi Jews. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:2918-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agalliu I, Gern R, Leanza S, et al. Associations of high-grade prostate cancer with BRCA1 and BRCA2 founder mutations. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:1112-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mersch J, Jackson MA, Park M, et al. Cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations other than breast and ovarian. Cancer 2015;121:269-75. Erratum in: Cancer 2015;121:2474-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nyberg T, Frost D, Barrowdale D, et al. Prostate Cancer Risks for Male BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: A Prospective Cohort Study. Eur Urol 2020;77:24-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leongamornlert D, Mahmud N, Tymrakiewicz M, et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations increase prostate cancer risk. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1697-701. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Castro E, Goh C, Olmos D, et al. Germline BRCA mutations are associated with higher risk of nodal involvement, distant metastasis, and poor survival outcomes in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1748-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Castro E, Romero-Laorden N, Del Pozo A, et al. PROREPAIR-B: A Prospective Cohort Study of the Impact of Germline DNA Repair Mutations on the Outcomes of Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:490-503. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Annala M, Struss WJ, Warner EW, et al. Treatment Outcomes and Tumor Loss of Heterozygosity in Germline DNA Repair-deficient Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 2017;72:34-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mateo J, Cheng HH, Beltran H, et al. Clinical Outcome of Prostate Cancer Patients with Germline DNA Repair Mutations: Retrospective Analysis from an International Study. Eur Urol 2018;73:687-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, et al. Germline DNA-repair Gene Mutations and Outcomes in Men with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Receiving First-line Abiraterone and Enzalutamide. Eur Urol 2018;74:218-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Messina C, Cattrini C, Soldato D, et al. BRCA Mutations in Prostate Cancer: Prognostic and Predictive Implications. J Oncol 2020;2020:4986365. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005;434:917-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 2005;434:913-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;740:364-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loriot Y, Massard C, Gross-Goupil M, et al. Combining carboplatin and etoposide in docetaxel-pretreated patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a prospective study evaluating also neuroendocrine features. Ann Oncol 2009;20:703-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hager S, Ackermann CJ, Joerger M, et al. Anti-tumour activity of platinum compounds in advanced prostate cancer-a systematic literature review. Ann Oncol 2016;27:975-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yap TA, Carden CP, Kaye SB. Beyond chemotherapy: targeted therapies in ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:167-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal R, Kaye SB. Ovarian cancer: strategies for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2003;3:502-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ashworth A, Lord CJ. Synthetic lethal therapies for cancer: what's next after PARP inhibitors? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15:564-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chernikova SB, Game JC, Brown JM. Inhibiting homologous recombination for cancer therapy. Cancer Biol Ther 2012;13:61-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gudmundsdottir K, Ashworth A. The roles of BRCA1 and BRCA2 and associated proteins in the maintenance of genomic stability. Oncogene 2006;25:5864-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer: a preplanned retrospective analysis of outcomes by BRCA status in a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:852-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:244-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banerjee S, Moore KN, Colombo N, et al. Maintenance olaparib for patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer and a BRCA mutation (SOLO1/GOG 3004): 5-year follow-up of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:1721-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2154-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;390:1949-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1274-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kristeleit R, Shapiro GI, Burris HA, et al. A Phase I-II Study of the Oral PARP Inhibitor Rucaparib in Patients with Germline BRCA1/2-Mutated Ovarian Carcinoma or Other Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:4095-106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swisher EM, Lin KK, Oza AM, et al. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): an international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:75-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oza AM, Tinker AV, Oaknin A, et al. Antitumor activity and safety of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients with high-grade ovarian carcinoma and a germline or somatic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: Integrated analysis of data from Study 10 and ARIEL2. Gynecol Oncol 2017;147:267-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- González-Martín A, Pothuri B, Vergote I, et al. Niraparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2391-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fong PC, Yap TA, Boss DS, et al. Poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase inhibition: frequent durable responses in BRCA carrier ovarian cancer correlating with platinum-free interval. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2512-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore KN, Secord AA, Geller MA, et al. Niraparib monotherapy for late-line treatment of ovarian cancer (QUADRA): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:636-48. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol 2019;20:e242. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gelmon KA, Tischkowitz M, Mackay H, et al. Olaparib in patients with recurrent high-grade serous or poorly differentiated ovarian carcinoma or triple-negative breast cancer: a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-randomised study. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:852-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murai J, Huang SY, Das BB, et al. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res 2012;72:5588-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dedes KJ, Wetterskog D, Mendes-Pereira AM, et al. PTEN deficiency in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinomas predicts sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Sci Transl Med 2010;2:53ra75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dinkic C, Jahn F, Zygmunt M, et al. PARP inhibition sensitizes endometrial cancer cells to paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. Oncol Lett 2017;13:2847-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Philip CA, Laskov I, Beauchamp MC, et al. Inhibition of PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway sensitizes endometrial cancer cell lines to PARP inhibitors. BMC Cancer 2017;17:638. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janzen DM, Paik DY, Rosales MA, et al. Low levels of circulating estrogen sensitize PTEN-null endometrial tumors to PARP inhibition in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther 2013;12:2917-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forster MD, Dedes KJ, Sandhu S, et al. Treatment with olaparib in a patient with PTEN-deficient endometrioid endometrial cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011;8:302-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gockley AA, Kolin DL, Awtrey CS, et al. Durable response in a woman with recurrent low-grade endometrioid endometrial cancer and a germline BRCA2 mutation treated with a PARP inhibitor. Gynecol Oncol 2018;150:219-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med 2017;377:523-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med 2018;379:753-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Bono J, Ramanathan RK, Mina L, et al. Phase I, Dose-Escalation, Two-Part Trial of the PARP Inhibitor Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Germline BRCA1/2 Mutations and Selected Sporadic Cancers. Cancer Discov 2017;7:620-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dhawan MS, Bartelink IH, Aggarwal RR, et al. Differential Toxicity in Patients with and without DNA Repair Mutations: Phase I Study of Carboplatin and Talazoparib in Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:6400-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Karihtala P, Moschetta M, et al. Combined Strategies with Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase (PARP) Inhibitors for the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer: A Literature Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019;9:87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Domchek SM, Postel-Vinay S, Im SA, et al. Olaparib and durvalumab in patients with germline BRCA-mutated metastatic breast cancer (MEDIOLA): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1/2, basket study. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:1155-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JM, Cimino-Mathews A, Peer CJ, et al. Safety and Clinical Activity of the Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Inhibitor Durvalumab in Combination With Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitor Olaparib or Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 1-3 Inhibitor Cediranib in Women's Cancers: A Dose-Escalation, Phase I Study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2193-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Konstantinopoulos PA, Waggoner SE, Vidal GA, et al. TOPACIO/Keynote-162 (NCT02657889): A phase 1/2 study of niraparib + pembrolizumab in patients (pts) with advanced triple-negative breast cancer or recurrent ovarian cancer (ROC)—Results from ROC cohort. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:106. [Crossref]

- Liu JF, Barry WT, Birrer M, et al. Combination cediranib and olaparib versus olaparib alone for women with recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1207-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Abson C, Moschetta M, et al. Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors: Talazoparib in Ovarian Cancer and Beyond. Drugs R D 2020;20:55-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turner N, Tutt A, Ashworth A. Hallmarks of 'BRCAness' in sporadic cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:814-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lord CJ, Ashworth A. BRCAness revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16:110-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kondrashova O, Scott CL. Clarifying the role of EMSY in DNA repair in ovarian cancer. Cancer 2019;125:2720-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies H, Glodzik D, Morganella S, et al. HRDetect is a predictor of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency based on mutational signatures. Nat Med 2017;23:517-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ray-Coquard I, Pautier P, Pignata S, et al. Olaparib plus Bevacizumab as First-Line Maintenance in Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2416-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2091-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marcotte R, Brown KR, Suarez F, et al. Essential gene profiles in breast, pancreatic, and ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Discov 2012;2:172-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kampmann M. CRISPRi and CRISPRa Screens in Mammalian Cells for Precision Biology and Medicine. ACS Chem Biol 2018;13:406-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dixit A, Parnas O, Li B, et al. Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens. Cell 2016;167:1853-1866.e17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Moschetta M, Karihtala P, et al. Development of new poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in ovarian cancer: Quo Vadis? Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1706. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gogola E, Duarte AA, de Ruiter JR, et al. Selective Loss of PARG Restores PARylation and Counteracts PARP Inhibitor-Mediated Synthetic Lethality. Cancer Cell 2018;33:1078-1093.e12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bunting SF, Callén E, Wong N, et al. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell 2010;141:243-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson SF, Cruz C, Greifenberg AK, et al. CDK12 Inhibition Reverses De Novo and Acquired PARP Inhibitor Resistance in BRCA Wild-Type and Mutated Models of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cell Rep 2016;17:2367-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garcia TB, Snedeker JC, Baturin D, et al. A Small-Molecule Inhibitor of WEE1, AZD1775, Synergizes with Olaparib by Impairing Homologous Recombination and Enhancing DNA Damage and Apoptosis in Acute Leukemia. Mol Cancer Ther 2017;16:2058-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim H, Xu H, George E, et al. Combining PARP with ATR inhibition overcomes PARP inhibitor and platinum resistance in ovarian cancer models. Nat Commun 2020;11:3726. [Crossref] [PubMed]

刘宇

复旦大学附属肿瘤医院(更新时间:2023-05-05)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Chebly A, Yammine T, Rassy E, Boussios S, Moschetta M, Farra C. Current evidence of BRCA mutations in genitourinary and gynecologic tumors: a scoping review. Precis Cancer Med 2022;5:17.