免疫治疗在间皮瘤治疗中的作用

背景介绍

间皮瘤是起源于胸膜腔、腹膜腔、鞘膜腔或心包腔间皮表面的一种隐匿性肿瘤,胸膜起源病例占其中的80%。恶性间皮瘤(Malignant mesothelioma,MM)发病因性别和地区而异,发病率从美国的10例/百万人到澳大利亚和英国的29例/百万人不等,且在男性中更为常见[1,2]。

恶性胸膜间皮瘤(Malignant pleural mesothelioma, MPM)的主要危险因素是石棉暴露,约占发病例数的80%[3]。由于暴露后存在20~50年的时滞,且上世纪70~80年代实施了石棉监管,MPM在发达国家的发病率在未来10年预计将达到峰值。吸烟与石棉接触虽都能增加肺癌患病风险,但并不是一项独立危险因素[4]。

间皮瘤通常发生在50~70岁,典型症状包括胸痛、呼吸困难和体重减轻[5]。在临床上区分MPM和良性胸腔积液十分困难[6]。对于疑似MPM的患者可采用影像学检查作为辅助,目前,国际间皮瘤小组(the International Mesothelioma Interest Group)建议用胸水细胞学检查诊断上皮样间皮瘤[7]。

MPM预后极差,现代治疗能为患者提供的收益极为有限[8]。组织学亚型是提示MPM预后的重要指标,在上皮样MM、双相型MM和肉瘤样MM中,患者的生存期呈递减态势[9]。

少数特定(<10%)患者在完成宏观上的切除术后可接受全身化疗、手术和/或放疗(Radiotherapy, RT)联合的多模式根治性治疗,以维持局部范围内的肿瘤控制。然而就目前为止,此类综合治疗尚无统一标准[10]。2018年,英国胸科协会(British Thoracic Society, BTS)反对一切形式的胸膜外肺切除术及除临床试验外的胸膜切除术和去皮质术[11]。BTS根据MAPS试验结果认为,贝伐单抗(Bevacizumab)联合一项含铂类二药化疗可有效提高患者生存率[12],多数诊断时已不能行根除术的患者在接受治疗后的中位生存期为12个月,当中含铂类二药化疗方案为其提供的中位生存收益为3个月[10]。

过去十年间,包括抗血管生成治疗和靶向治疗在内的许多MPM治疗研究已开展试验,但均收效甚微[12]。在本次回顾性研究中,我们将讨论免疫治疗在MPM治疗中所发挥的作用。

研究方法

为达研究目的,本次回顾性研究在公开临床试验数据库(https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/)中检索了主题词“胸膜间皮瘤(pleural mesothelioma)”,共得到187个结果。然后将目标集中于免疫治疗试验,排除标准包括非治疗性试验,专注于能量疗法(包括放疗)及全身化疗、激酶抑制剂和其他非抗体抑制剂的治疗性研究,以及存疑、撤回或状态未知的研究。

最终共有21项试验符合纳入条件,将其分为免疫检查点抑制剂(Immune checkpoint inhibitors, ICIs)组和非ICIs组2个组。

此外,对已发表的数据,我们亦进行了文献回顾。

MPM的肿瘤免疫微环境

MPM通常被认为起源于胸膜接触石棉纤维后产生的慢性炎症。

一项关于肿瘤微环境的研究发现,慢性间质性炎性反应是患者生存率的独立预测因素[13]。对上皮样MPM肿瘤和肿瘤相关间质免疫反应的研究提示,CD163+肿瘤相关巨噬细胞增多及CD8+肿瘤浸润淋巴细胞(Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes, TILs)减少与预后不良有关,CD163+肿瘤相关巨噬细胞减少和CD20+淋巴细胞增多则提示预后较好[14]。多项研究已证实,B细胞、T细胞和巨噬细胞均对预后发挥关键作用[14-17]。其他研究发表的数据显示,通过对细胞抑制性受体[18]和包括C-C基序趋化因子配体2(C-C motif chemokine ligand 2,CCL2)在内的趋化因子(后者为促肿瘤M2巨噬细胞募集的关键因素)分析后发现,MPM具有免疫抑制功能[19]。为使免疫微环境向抗肿瘤免疫反应的方向转化,目前有数项免疫调节剂研究正在进行。

ICIs

通常情况下,肿瘤新抗原(Neoantigen)诱导的免疫反应涉及效应T细胞和TILs。肿瘤细胞可通过上调细胞表面的抑制性配体适应环境,TILs则通过表达与该类配体相结合的抑制性受体导致T细胞的凋亡和免疫抑制。这些抑制性受体亦被称为免疫检查点,作为调节系统可防止自身免疫反应,但同时也在肿瘤的发展中起到了关键作用。新型抗肿瘤药物ICIs是一种能阻断抑制性免疫信号、恢复抗肿瘤免疫反应的单克隆抗体(monoclonal antibodies,mAbs),其原理涉及与检查点通路的相互作用,包括细胞毒性T淋巴细胞相关抗原4(Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4,CTLA-4)、程序性死亡蛋白1(Programmed death protein 1,PD-1)及其配体(PD-L1)。

抗CTLA-4(Anti CTLA-4)

CTLA-4是由活化T细胞和调节性T细胞(Regulatory T cells,Tregs)表达的一种糖蛋白,可作为T细胞介导免疫反应的抑制性调节因子。CTLA-4与共刺激受体CD-28竞争抗原提呈细胞(Antigen presenting cells,APCs)表达的B7配体(CD-80和CD-86),通过CTLA-4/CD-80结合可以直接抑制T细胞的效应功能。因此,阻断CTLA-4与其配体相互作用的单克隆抗体能增强包括抗肿瘤免疫在内的免疫反应。目前已有两种抗CTLA药物,即伊匹单抗(Ipilimumab)和曲美木单抗(Tremelimumab)。

伊匹单抗是一种IgG1单克隆抗体,也是第一个被证明对患者生存有益的ICI药物。在初期应用于黑色素瘤研究之后,伊匹单抗的单用或联合PD1阻断剂使用已存在于多种肿瘤的疗效性研究之中。治疗MPM方面,伊匹单抗主要联合PD1阻断剂评估,因此本研究将与PD1抑制剂一起讨论伊匹单抗的疗效。

曲美木单抗是一种选择性人类IgG2抗CTLA-4单克隆抗体,在MESOT-TREM-2008和MESOT-TREM-2012两个小型2期研究中提示有效,2015年4月被美国食品和药物管理局(Food and Drug Administration,FDA)批准用于MPM的治疗[20,21]。MESOT-TREM-2008作为一项2期研究评估了曲美木单抗在MPM患者二线治疗中的作用,除得到7%的客观缓解率(Objective response rate,ORR)外,患者的疾病控制率(Disease control rate,DCR)和2年生存率也分别达到了31%和36%[20]。上述可喜成果在2期MESOT-TREM-2012试验的29个附加MPM二线治疗病例中得到了证实[21]。另一项研究中,曲美木单抗按照定量强化方案给药,每4周10 mg/kg静脉注射,共给药6次,后根据以往转移性黑色素瘤患者的药代动力学数据予每12周给药[22]。结果ORR为14%,DCR为52%,中位反应时间为10.9个月,总生存期(Overall survival,OS)为11.3个月。7%的病例中观察到了3~4级治疗相关毒性事件。

在此基础上,Maio等进行了一项大型2b期随机安慰剂对照研究DETERMINE试验。该试验对共计571例患胸膜(占比95%)或腹膜间皮瘤患者行曲美木单抗治疗,方案与MESOT-TREM-2012相同[23]。然而,该试验并未得到OS或DCR收益,因此不推荐对MPM行抗CTLA-4单药治疗。

抗PD-1(Anti PD-1)

PD-1是一种表达于活化T细胞、活化B细胞和自然杀伤细胞的跨膜抑制性免疫受体[24],可结合间质细胞和肿瘤细胞表达的PD-L1、PD-L2,并通过相互作用诱导T细胞衰竭,减少细胞因子释放,抑制细胞生长,最终导致T细胞凋亡。免疫调节单克隆抗体阻断PD-1或PD-L1可重启T细胞活化,释放针对肿瘤的免疫反应[25]。高达60%的MPM样本中可发现PD-L1表达,且表达率在肉瘤样组织类型中较高,与不良预后密切相关。存在PD-L1表达的晚期间皮瘤患者的中位生存期为5个月,而PD-L1表达阴性患者的中位生存期则为14.5个月[26-29]。

纳武单抗(Nivolumab)是一种完全性人类抗PD1单克隆抗体,并已在多项MPM试验中被研究过。NIVOMES试验作为一项单臂2期临床试验,先前已在34例有治疗史的MPM患者中进行,起初每2周予纳武单抗,剂量为3 mg/kg,结果3个月的ORR为24%,DCR为47%,疗效反应与PD-L1表达无关,3~4级不良事件的发生率为26%[30]。以上成果在2期MERIT研究中得到了验证。该试验通过对34例经过二线或三线治疗的MPM患者行纳武单抗治疗,平均剂量每2周240 mg,静脉注射,结果发现ORR为29.4%,DCR为67.6%,无进展生存期(Progress free survival,PFS)为6.1个月,而在结果分析时尚未抵达中位生存期[31]。

另有一项正在进行的3期双盲安慰剂对照研究CONFIRM试验,其目的为证实纳武单抗对有治疗史的间皮瘤患者有益。该研究将纳入至少经两线化疗后出现进展的患者,并将其随机分配到纳武单抗治疗组(平均剂量240 mg)和安慰剂组,近期将在英国开放,预计招募患者数336例[32]。

帕博利珠单抗(Pembrolizumab)是另一种已用于MPM研究的抗PD-1单克隆抗体。在针对治疗后MPM患者的1B期多队列研究Keynote 028试验中,共25例MPM患者每2周予10 mg/kg帕博利珠单抗,部分缓解(Partial response, PR)者达20%,疾病稳定(Stable disease,SD)者为52%,中位缓解持续时间(Duration of response,DOR)为1年。值得关注的是,患者的中位PFS为5.4个月,中位生存期则为18.0个月[33]。这些令人鼓舞的结果使帕博利珠单抗治疗MPM试验开展更加丰富。

在一项针对有治疗史的胸膜或腹膜间皮瘤的2期临床试验中,共计65例间皮瘤患者(胸膜占比86%,腹膜占比14%)被予每3周200 mg帕博利珠单抗,总体ORR为20%;值得注意的是,肉瘤样的亚型的ORR为40%。患者中位PFS为4.5个月,OS为11.5个月。近20%的病例发生了3-5级毒性事件。该试验中PD-L1的表达与ORR和PFS呈正比关系趋势[34]。

一项名为PROMISE-meso的大型多中心随机3期试验目前正在进行。该试验纳入144个有治疗史的MPM患者,将帕博利珠单抗和标准化疗进行比较,帕博利珠单抗予每3周200 mg的固定剂量[35]。对帕博利珠单抗所能提供的收益,该试验可能予以更准确的回答。另一项相似的大型2/3期随机3臂试验则正在对比帕博利珠单抗治疗、标准化疗和二者联合用药的疗效[36]。

在一项1期单臂临床试验评估中,帕博利珠单抗正用于可根除治疗MPM患者的新辅助治疗。患者在此将接受3周期的200 mg平剂量帕博利珠单抗治疗,然后是手术切除,以及铂类-培美曲塞辅助化疗[37]。

与此同时,多项试验正就帕博利珠单抗联合其他类型疗法的效果进行研究。一项1期临床试验正在评估帕博利珠单抗联合影像引导下手术切除和化疗对MPM的安全性及有效性[38]。

另有一项小规模1期安全性试验旨在评估肺部完整MPM患者放疗后的帕博利珠单抗辅助疗效[39]。

抗PD-L1单克隆抗体(Anti-PD-L1 mAb)

PD-L1通过阻断肿瘤配体、而非T细胞上的受体发挥作用,其基本生物学原理与PD-1抑制相同。一项1b期JAVELIN试验评估了抗PD-L1抗体Avelumab的临床疗效,共纳入53例采用铂类-培美曲塞方案后进展的MPM患者,结果ORR为9%(5例),疾病控制率为58%,中位缓解时间为15.2个月。肿瘤PD-L1阳性患者的ORR(19%)高于阴性患者(7%),最常见的治疗相关毒性事件包括疲劳、发热、输液相关反应和皮肤不良反应,3~4级不良事件占比9%。对该药的研究仍需更进一步[40]。

另一种抗PD-L1抗体Atezolimumab(T药)正通过各项试验被予评估。一项正在进行的大型随机3期试验对比了Atezolimumab联合贝伐单抗(Bevacizumab)、化疗以及贝伐单抗联合化疗作为一线方案对晚期MPM的疗效[41]。其他小型试验则在研究Atezolimumab单药对MPM化疗后的疗效。此外,还有评估化疗联合免疫治疗作为新辅助治疗方案的研究[42,43]。

一项2期单臂DREAM试验正在研究抗PD-L1单抗Durvalumab(I药)与MPM一线化疗的联合效果。初步结果显示,54例患者的ORR和PFS分别为惊人的61%和71%。但是,发生3级及以上不良事件的患者占到了57%[44]。

PD-1和 CTLA-4联合阻断(Combination PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockade)

在针对间皮瘤的试验中,由于Tremelimumab单药未能达到初期预计效果,因而被ICI联合治疗试验所取代。在一项纳入40例无法行根除治疗间皮瘤患者的2期单臂临床试验中,研究者采用Tremelimumab联合抗PD-L1单克隆抗体Durvalumab,结果ORR为28%,中位缓解期为16.1个月,中位总生存期为16.6个月。PD-L1的表达与反应预后无关。18%的患者存在3~4级治疗相关不良事件[45]。

相同联合方案作为新辅助治疗的研究亦在进行中,治疗时间设定在手术切除前1~6周。主要观察指标包括瘤内CD8 T细胞与Tregs的比值(CD8/Treg),诱导型T细胞共刺激因子(Inducible T-cell co-stimulator,ICOS),CD4 T细胞百分比,以及PD-L1的表达[46]。

纳武单抗和抗CTLA-4药物伊匹单抗联合应用已被证明对黑色素瘤和肾癌有效,当前正在进行的研究则涵盖了针对间皮瘤在内的多种肿瘤。一项名为INITIATE的2期单臂试验纳入了34例MPM患者,采用纳武单抗和伊匹单抗联用后提示有效,PR为29%,DCR为68%,但出现3级毒性事件者占比达34%[47]。接下来开展的随机非比较性IFCT-1501 MAPS2试验评估了纳武单抗对比纳武单抗联合伊匹单抗对MPM治疗后患者的疗效和安全性,纳武单抗的给药方案为每2周3 mg/kg,联合用药方案则在纳武单抗方案的基础上增加伊匹单抗每6周1 mg/kg,主要观察指标为3个月的DCR。在意向性治疗人群中,单药治疗与联合治疗的3个月DCR分别为40%和52%。14%的纳武单抗治疗患者和26%的联合治疗患者出现了3~4级不良事件,联合治疗患者中还出现了3例不良事件相关性死亡。肿瘤PD-L1的阳性表达(截止值为1%)与两组客观反应或疾病控制的升高有关,但仅有纳武单抗治疗组患者的PD-L1肿瘤阳性表达与OS的延长具有相关性[48]。

该试验因而证明了其他小型抗PD-L1试验的成果,即抗PD-1或抗PD-L1抗体对MPM具有活性。目前,我们仍需更大规模的临床试验以证实联合用药的确优于PD-1阻断剂单药使用。

鉴于ICI在后期试验中的有效性,正在进行的3期随机临床试验Checkmate 743旨在评估相对于MPM标准一线化疗方案铂类-培美曲塞,纳武单抗联合伊匹单抗的一线治疗作用[49]。

非检查点抑制剂免疫治疗:T细胞介导治疗

如正在进行的各项临床试验所示,学界目前正通过研发创新性细胞治疗控制MPM,包括激活免疫系统在内的各类新技术。过继细胞转移(Adoptive cell transfer,ACT)作为免疫疗法的一种,需从外周血或肿瘤本身收集宿主免疫细胞,然后对靶向免疫细胞进行分离、修饰和体外扩增,并将修饰后的免疫细胞重新注入患者体内作为治疗[50]。ACT的优势在于,靶向效应细胞可结合特异性肿瘤相关抗原,并直接导致细胞毒性。ACT包括2个主要类别:嵌合抗原受体(chimeric antigen receptor,CAR)修饰的T细胞,以及TIL输注。

T细胞介导治疗的方法之一是使用CARs创造一种肿瘤特异性抗原受体,并将其与T细胞之类的效应细胞结合[51]。CAR的构成包括一个与胞外抗原结合的结合域,与一个或多个细胞内信号结构域相连接[52]。构建完成后,CAR将被转入自体T细胞并重新注射到患者体内作为治疗。CARs曾被用于治疗儿童急性淋巴母细胞性白血病,因效果极为显著大大推动了该技术的发展[51]。根据抗体和共刺激域的不同,CAR-T细胞可拥有不同的作用靶点。间皮素作为一种细胞表面糖蛋白,在多达95%的上皮样MPM样本中高表达,但在肉瘤样组织类型中有10%~15%的样本未发现表达[53]。间皮素的过度表达同时也存在于其他肿瘤类型中。由于在正常组织中表达有限,间皮素因而有希望作为一类肿瘤相关抗原靶点。此外,一些临床前研究和临床研究已发现,间皮素与肿瘤的发生及侵袭性关系密切[54]。在部分临床前研究中,针对间皮素的CARs在注射后可显著减小肿瘤大小[55],但反应异质性较高,可能与靶抗原的表达缺失有关[56]。

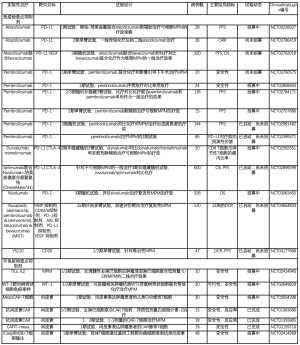

当前正在进行的MPM相关1期CAR-T细胞试验设计多种多样,见表1[57-62]。在一项1期试验中,针对包括转移性胰癌、浆液性上皮性卵巢癌和MPM在内的表达间皮素肿瘤使用了转导为慢病毒的靶向间皮素CAR-T细胞和/不和环磷酰胺一起静脉给药[61]。另2项更进一步的1/2期试验则正在研究静脉注射抗间皮素CAR-T细胞的效果[60,62]。

Full table

同样,研究者正在采用胸腔内注入靶向间皮素CAR-T细胞的方法治疗肺癌、乳腺癌或MPM起源的恶性胸膜疾病。该试验有1臂包括帕博利珠单抗,在11例患者中有反应者为8例,提示初期效果良好[59]。

本文讨论的第二项ADT免疫治疗策略为自体TILs输注。TIL治疗最初在恶性黑色素瘤方面提示效果突出,但在应用到其他恶性肿瘤时遇到了些许瓶颈。在保留特异性及功能的前提下,提取稀少的肿瘤反应淋巴细胞,分离,然后行T细胞扩增,具有较大的技术难度[52]。此外,延长TIL治疗的临床反应需减少淋巴细胞,后者则伴有显著的感染风险[50]。

在MPM治疗方面,一项1/2期试验正在研究去淋巴细胞后使用环磷酰胺和氟达拉滨序贯TILs静脉注射治疗的安全性和有效性,接受输注后再使用2周的小剂量白细胞介素2治疗,以促进TIL的连续性增殖及活性[63]。

另一种治疗方法是肿瘤疫苗接种,该方法包括疫苗刺激后激活特异性免疫应答,是基于肿瘤相关抗原的发现而发展起来的治疗技术。接种疫苗后,自体树突状细胞可捕获并识别肿瘤抗原,通过表达诸如细胞因子的共刺激分子增强免疫反应。一些研究表明,MPM常表达高水平的WT1,后者为一种在癌细胞中负责调节基因表达的蛋白质[64]。一项正在招募患者的研究旨在评估WT1疫苗联合铂类化疗在MPM一线治疗中的效果。

由此看来,从科学角度出发,新型ADT策略或具有良好疗效,相关试验结果可能瞬间改变难治性MPM的治疗前景,因此备受期待。

目前有21项正在进行的MPM相关免疫治疗评估性试验,提示学界对该疗法的期望值极高(表1)。

结论

MPM虽是一种罕见肿瘤,但其发病率将在未来十年预计达到峰值。因此,鉴于当前有限的治疗选择,对该病确立安全有效的治疗策略是一项极有价值的挑战。免疫治疗包括但不限于检查点抑制,是一种前景突出且快速有效的治疗方法。

MPM的两药化疗一线治疗策略已经建立完善,而增加ICI药物所能带来的收益则仍有待证明。同样地,虽有正在进行中的大规模试验,目前的研究结果尚不能使ICI得到一线治疗的资格。

由于标准的二线治疗仍待确立,ICI基于1/2期试验的成果体现出了较强的竞争力。根据当前数据,不推荐使用抗CTLA-4单药治疗。反之,PD-1阻断和联合治疗则具有较好的应用前景。

此外,CAR-T细胞和自体TIL输注在MPM治疗中的潜力将被很快阐明。最后,以上治疗方法必须与其他疗法相结合,以便尽可能为间皮瘤患者提供最佳的疗效。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors Alfredo Addeo and Giuseppe Banna for the series “Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)” published in Precision Cancer Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/pcm.2019.06.01). The series “Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. AF reports personal fees from MSD, BMS, Roche, Astellas, outside the submitted work. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Berry G, de Klerk NH, Reid A, et al. Malignant pleural and peritoneal mesotheliomas in former miners and millers of crocidolite at Wittenoom, Western Australia. Occup Environ Med 2004;61:e14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Musk AW, de Klerk NH. Epidemiology of malignant mesothelioma in Australia. Lung Cancer 2004;45:S21-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Delgermaa V, Takahashi K, Park EK, et al. Global mesothelioma deaths reported to the World Health Organization between 1994 and 2008. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:716-24, 24A-24C.

- Carbone M, Kratzke RA, Testa JR. The pathogenesis of mesothelioma. Semin Oncol 2002;29:2-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson M, Wiggins J. Statement on malignant mesothelioma in the UK. Thorax 2002;57:187. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brims FJ, Maskel NA. Prognostic factors for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Current Respiratory Care Reports 2013;2:100-8. [Crossref]

- Hjerpe A, Ascoli V, Bedrossian CW, et al. Guidelines for the cytopathologic diagnosis of epithelioid and mixed-type malignant mesothelioma: Complementary Statement from the International Mesothelioma Interest Group, Also Endorsed by the International Academy of Cytology and the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology. Diagn Cytopathol 2015;43:563-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang H, Testa JR, Carbone M. Mesothelioma epidemiology, carcinogenesis, and pathogenesis. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2008;9:147-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hassan R, Alexander R, Antman K, et al. Current treatment options and biology of peritoneal mesothelioma: meeting summary of the first NIH peritoneal mesothelioma conference. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1615-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2636-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Bondt C, Psallidas I, Van Schil PEY, et al. Combined modality treatment in mesothelioma: a systemic literature review with treatment recommendations. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2018;7:562-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zalcman G, Mazieres J, Margery J, et al. Bevacizumab for newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma in the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study (MAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;387:1405-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tano ZE, Chintala NK, Li X, et al. Novel immunotherapy clinical trials in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Transl Med 2017;5:245. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ujiie H, Kadota K, Nitadori JI, et al. The tumoral and stromal immune microenvironment in malignant pleural mesothelioma: A comprehensive analysis reveals prognostic immune markers. Oncoimmunology 2015;4:e1009285. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anraku M, Cunningham KS, Yun Z, et al. Impact of tumor-infiltrating T cells on survival in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;135:823-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cornelissen R, Lievense LA, Maat AP, et al. Ratio of intratumoral macrophage phenotypes is a prognostic factor in epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma. PLoS One 2014;9:e106742. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamada N, Oizumi S, Kikuchi E, et al. CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes predict favorable prognosis in malignant pleural mesothelioma after resection. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010;59:1543-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lizotte PH, Jones RE, Keogh L, et al. Fine needle aspirate flow cytometric phenotyping characterizes immunosuppressive nature of the mesothelioma microenvironment. Sci Rep 2016;6:31745. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chene AL, d'Almeida S, Blondy T, et al. Pleural Effusions from Patients with Mesothelioma Induce Recruitment of Monocytes and Their Differentiation into M2 Macrophages. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1765-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calabro L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, et al. Tremelimumab for patients with chemotherapy-resistant advanced malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1104-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calabro L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, et al. Efficacy and safety of an intensified schedule of tremelimumab for chemotherapy-resistant malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med 2015;3:301-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calabro L, Ceresoli GL, di Pietro A, et al. CTLA4 blockade in mesothelioma: finally a competing strategy over cytotoxic/target therapy? Cancer Immunol Immunother 2015;64:105-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maio M, Scherpereel A, Calabrò L, et al. Tremelimumab as second-line or third-line treatment in relapsed malignant mesothelioma (DETERMINE): a multicentre, international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1261-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2443-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Huang S, Gong D, et al. Programmed death-1 upregulation is correlated with dysfunction of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes in human non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Mol Immunol 2010;7:389-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Awad MM, Jones RE, Liu H, et al. Cytotoxic T Cells in PD-L1-Positive Malignant Pleural Mesotheliomas Are Counterbalanced by Distinct Immunosuppressive Factors. Cancer Immunol Res 2016;4:1038-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cedres S, Ponce-Aix S, Pardo-Aranda N, et al. Analysis of expression of PTEN/PI3K pathway and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM). Lung Cancer 2016;96:1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khanna S, Thomas A, Abate-Daga D, et al. Malignant Mesothelioma Effusions Are Infiltrated by CD3(+) T Cells Highly Expressing PD-L1 and the PD-L1(+) Tumor Cells within These Effusions Are Susceptible to ADCC by the Anti-PD-L1 Antibody Avelumab. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1993-2005. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mansfield AS, Roden AC, Peikert T, et al. B7-H1 expression in malignant pleural mesothelioma is associated with sarcomatoid histology and poor prognosis. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:1036-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quispel-Janssen J, van der Noort V, de Vries JF, et al. Programmed Death 1 Blockade With Nivolumab in Patients With Recurrent Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:1569-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goto Y, Okada, M., Kijima, T., et al. A phase ii study of nivolumab: a multicenter, open-label, single arm study in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MERIT). Association for the Study of Lung Cancer 18th World Conference on Lung Cancer; Yokohama, Japan2017.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. CheckpOiNt Blockade For Inhibition of Relapsed Mesothelioma (CONFIRM). 2018, July 24. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03063450.

- Alley EW, Lopez J, Santoro A, et al. Clinical safety and activity of pembrolizumab in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (KEYNOTE-028): preliminary results from a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:623-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Desai A, Karrison T, Rose B, et al. OA08.03 Phase II Trial of Pembrolizumab (NCT02399371) In Previously-Treated Malignant Mesothelioma (MM): Final Analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:S339. [Crossref]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. PembROlizuMab Immunotherapy Versus Standard Chemotherapy for Advanced prE-treated Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (PROMISE-meso). 2018, June 26. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02991482

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. 2019, April 10. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02784171.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A Pilot Window-Of-Opportunity Study of the Anti-PD-1 Antibody Pembrolizumab in Patients With Resectable Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. 2018, January 4. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02707666

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Pembrolizumab in Combination With Chemotherapy and Image-Guided Surgery for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MPM). 2019, April 16. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03760575

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab After Radiation Therapy for Lung-Intact Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. 2019, March 5. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02959463

- Hassan R, Thomas A, Nemunaitis JJ, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Avelumab Treatment in Patients With Advanced Unresectable Mesothelioma: Phase 1b Results From the JAVELIN Solid Tumor Trial. JAMA Oncol 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Atezolizumab With Bevacizumab and Chemotherapy vs Bevacizumab and Chemotherapy in Early Relapse Ovarian Cancer. 2018, December 18. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03353831

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study of Atezolizumab in Unresectable or Advaced Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. 2018, December 25. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03786419

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Atezolizumab, Pemetrexed Disodium, Cisplatin, and Surgery With or Without Radiation Therapy in Treating Patients With Stage I-III Pleural Malignant Mesothelioma. 2019, May 1. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03228537

- Nowak AK, Lesterhuis WJ, Hughes B, et al. DREAM: A phase II study of durvalumab with first line chemotherapy in mesothelioma—First results. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:8503. [Crossref]

- Calabro L, Morra A, Giannarelli D, et al. Tremelimumab combined with durvalumab in patients with mesothelioma (NIBIT-MESO-1): an open-label, non-randomised, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6:451-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. MEDI4736 Or MEDI4736 + Tremelimumab In Surgically Resectable Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. 2019, January 16. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02592551

- Disselhorst MJ, Quispel-Janssen J, Lalezari F, et al. Ipilimumab and nivolumab in the treatment of recurrent malignant pleural mesothelioma (INITIATE): results of a prospective, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:260-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scherpereel A, Mazieres J, Greillier L, et al. Nivolumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with relapsed malignant pleural mesothelioma (IFCT-1501 MAPS2): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, non-comparative, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:239-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Study of Nivolumab Combined With Ipilimumab Versus Pemetrexed and Cisplatin or Carboplatin as First Line Therapy in Unresectable Pleural Mesothelioma Patients (CheckMate743). 2019, April 29. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02899299

- Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive cell transfer as personalized immunotherapy for human cancer. Science 2015;348:62-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2015;385:517-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Riviere I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov 2013;3:388-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baldo P, Cecco S. Amatuximab and novel agents targeting mesothelin for solid tumors. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:5337-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Servais EL, Colovos C, Rodriguez L, et al. Mesothelin overexpression promotes mesothelioma cell invasion and MMP-9 secretion in an orthotopic mouse model and in epithelioid pleural mesothelioma patients. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:2478-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adusumilli PS, Cherkassky L, Villena-Vargas J, et al. Regional delivery of mesothelin-targeted CAR T cell therapy generates potent and long-lasting CD4-dependent tumor immunity. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:261ra151. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1507-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Hara M, Stashwick C, Haas AR, et al. Mesothelin as a target for chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells as anticancer therapy. Immunotherapy 2016;8:449-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klampatsa A, Haas AR, Moon EK, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell Therapy for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MPM). Cancers (Basel) 2017;9: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Malignant Pleural Disease Treated With Autologous T Cells Genetically Engineered to Target the Cancer-Cell Surface Antigen Mesothelin. 2019, May 17. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02414269

- ClinicalTrials.gov. CAR T Cell Receptor Immunotherapy Targeting Mesothelin for Patients With Metastatic Cancer. 2019, May 22. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01583686

- ClinicalTrials.gov. CART-meso in Mesothelin Expressing Cancers. 2019, February 26. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02159716.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Autologous Redirected RNA Meso-CIR T Cells. 2017, September 19. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01355965

- ClinicalTrials.gov. TILs & Low-Dose IL-2 Therapy Following Cyclophosphamide and Fludarabine in Pleural Mesothelioma Patients. 2019, February 5. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02414945

- Thomas A, Hassan R. Immunotherapies for non-small-cell lung cancer and mesothelioma. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e301-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

朱睿

上海中医药大学中医临床七年制硕士(已毕业),研究方向为中西医结合防治恶性肿瘤。近五年发表论文6篇,申请专利1项。2019至今兼职医学期刊编辑工作,作为主笔完成文章修改编撰90余稿。(更新时间:2021/8/18)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Colarusso G, Terzic J, Achard V, Friedlaender A. The role of immunotherapy in mesothelioma. Precis Cancer Med 2019;2:21.