ALK重排的非小细胞肺癌的精准治疗实施

前言

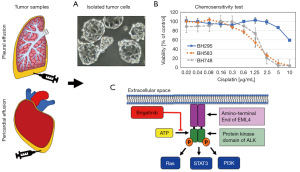

非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)约占所有肺癌病例的85%,初诊时多属于晚期,预后较差。以化疗为主的全身治疗,临床疗效非常有限,中位总生存期(OS)不到1年[1]。然而,由于发现特定的基因改变以及靶向治疗的发展,NSCLC患者的预后得到显著改善[2]。其中,以表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)突变发生最多见,而间变性淋巴瘤激酶(ALK)基因重排仅见于3%~7%的NSCLC患者中。与其他肺癌人群相比,ALK基因重排在腺癌组织类型、不吸烟或轻度吸烟的NSCLC患者中发生率较高,且发病年龄较轻[3-5]。ALK是胰岛素受体家族的一种酪氨酸激酶,参与正常细胞的增殖和神经发育过程[6]。ALK重排首次在淋巴瘤中被发现,2007年在NSCLC中发现致癌棘皮动物微管相关蛋白4(EML4)-ALK重排[3]。在肿瘤细胞中,ALK激活后的下游活性导致癌细胞增殖和代谢增加,细胞骨架重塑、迁移和细胞存活[7]。ALK受体的对应配体是多效蛋白和肝素结合因子[8]。ALK重排患者多为从不吸烟或轻度吸烟(少于10包/年)。肿瘤多位于肺门中央部位,确诊时通常为晚期,易发生脑和肝转移,继发胸腔积液和心包积液,这进一步证实了这种肺癌亚型的侵袭性较强[9, 10]。

克唑替尼是原癌基因MET的酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(TKI),同时又是ALK重排的抑制剂。根据Ⅰ期临床试验(ROFILE1001)结果,美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)批准克唑替尼用于晚期ALK重排NSCLC患者治疗[11]。与系统化疗相比,第一代ALK抑制剂克唑替尼、第二代ALK抑制剂色瑞替尼和艾乐替尼均可延长无进展生存期(PFS)与提高客观缓解率(ORR)[12]。而且,ALK抑制剂的颅内反应率也较化疗更好。总体而言,ALK抑制剂在ALK阳性NSCLC中是安全有效的药物。目前,共有四种第二代ALK抑制剂克唑替尼、色瑞替尼、艾乐替尼和布加替尼,以及第三线抑制剂劳拉替尼均被批准用于临床实践,还有更多正在研发[13]。

ALK重排

ALK基因最初于1994年在间变性大细胞淋巴瘤中被发现,2007年Soda等在NSCLC中首次发现ALK重排,且发生在ALK基因和EML4之间,导致基因倒位或易位[3]。ALK基因属于胰岛素受体超家族,编码跨膜酪氨酸激酶受体,包括胞外段、跨膜段和胞质受体激酶段。EML4-ALK易位导致胞质中高致性的驱动突变发生(图1)。而ALK的断裂点位于外显子20,许多融合突变体是通过与EML4外显子2、6、13、14、15、18和20等不同断裂点的融合而产生,突变频率分别为V1 (54.5%)、V2 (10%)、V3a/V3b (34%)与V5a (1.5%)等[14-16]。迄今为止,关于特定EML4-ALK变异作为疗效预测的潜在标志物的研究极少[17]。一项研究纳入67名具有EML4-ALK融合突变体1、2和3a/3b的IV期肺癌患者,发现V3 (3a/3b)突变体的亚组患者初诊时转移部位更多、一或二线ALK抑制剂治疗后进展更早、接受铂类化疗和全脑放疗更多,总体OS也更差[16,18]。ALK激酶结构域的二聚化触发经典途径,如MAPK、PI3K/mTOR、JAK-STAT、SHH等。EML4基因启动子控制融合蛋白,继而导致ALK过表达和增强酪氨酸激酶活性[19]。在NSCLC中发现了超过19种不同的ALK融合基因,包括EML4、KIF5B、KLC1和TPR[20]。第一个鉴别的耐药点突变是C1156Y和L1196M。随后,其他几个耐药点突变陆续被发现,包括G1269A、F1174L、1151Tin、L1152R、S1206Y、I1171T、G1202、D1203N和V1180L。

与常用的荧光原位杂交(FISH)相比,ALK免疫组织化学(IHC)用于筛选检测所需时间短、成本低、要求掌握的专业知识也更少[21,22]。此外,二代测序(NGS)可识别ALK融合伙伴基因、ALK突变和非靶基因改变等[23]。特定NGS检测的灵敏度受混杂因素影响,如肿瘤细胞纯度(用正常细胞DNA稀释肿瘤信号)和给定样本中存在多个肿瘤克隆(肿瘤内异质性或克隆多样性)。然而,对于大多数成患者,全转录组测序成本更高,且检测周期更长,不利于临床诊治。还有,转移癌基因组与原发肿瘤就有很大差异[24]。此外,肿瘤对靶向治疗发生耐药,主要有两点:(I)获得性耐药机制;(II)达尔文的“适者生存”机制:肿瘤内存在耐药克隆,这也正是肿瘤耐药与疾病进展的重要原因[25,26]。

ALK重排的NSCLC治疗

克唑替尼是第一个在随机Ⅲ期试验中应用的ALK-TKI药物,结果显示克唑替尼的ORR显著高于化疗(65% vs 20%)[27,28],且生活质量也明显提高。因此,克唑替尼被列为一线和二线治疗的新标准。与多西他赛或培美曲塞相比,克唑替尼二线治疗的ORR为65%,且4个月的PFS获益也更好。与EGFR-TKI一样,ALK抑制剂在治疗1年内难免发生耐药[29]。在ALK重排的NSCLC患者中,只有30%的获得性克唑替尼耐药是由于ALK的各种继发性突变,而其余70%则是由于其他机制所致,且绝大多数新发或进展性病变在颅内发生[30,31]。在克唑替尼失败后,第二代抑制剂色瑞替尼和艾乐替尼已经显示出较好的临床疗效,特别是颅内的疗效比克唑替尼更好。因此,2014年4月FDA加速批准色瑞替尼用于克唑替尼治疗出现进展的患者。2015年12月、2017年4月相继批准了艾乐替尼、布加替尼用于以上相同适应症[32]。

ALK抑制剂的耐药

ALK-TKI的耐药机制分为两种:(I)ALK依赖性“在靶”机制:包括继发性ALK突变和扩增;(II)ALK非依赖性“脱靶”机制:包括替代信号通路和癌细胞谱系转化[33,34]。在克唑替尼耐药中,继发突变发生率为20-30%;但对于第二、三代ALK抑制剂耐药的患者,ALK继发耐药突变频率增加到50%~70%。其中,常见的耐药突变为G1202R,分别占色瑞替尼、艾乐替尼和布加替尼耐药患者的21%、29%和43%[35],而第三代ALK抑制剂劳拉替尼可克服G1202R耐药突变[36]。此外,ALK非依赖性耐药机制还包括EGFR、KRAS、BRAF、MET、HER2和KIT的改变[37]。因此,研发新一代ALK-TKI以克服这些耐药模式十分迫切。这些药物包括色瑞替尼、艾乐替尼、布加替尼、恩沙替尼和劳拉替尼。布加替尼对克唑替尼耐药的ALK突变型NSCLC具有良好的抗癌活性[38]。布加替尼是一种多激酶抑制剂,对ALK、ROS1、FLT3、FLT3突变体、IGFR-1R和T790M突变EGFR均有抑制作用。与克唑替尼、色瑞替尼和艾乐替尼相比,布加替尼对所有17种继发性ALK突变,包括C1156Y、I1171S/T、V1180L、L1196M、L1152R/P、E1210K、G1269A和最难治的G1202R突变显示出更好的抑制作用[39]。G1202R是迄今为止与三种之前获批ALK抑制剂的临床耐药密切相关的唯一突变。

劳拉替尼是目前临床上获批的最新ALK抑制剂[5]。劳拉替尼的血脑屏障渗透性极高,且对获得性耐药突变(包括ALKG1202R突变)具有良好的疗效。第二代ALK抑制剂应用后,这种突变频率会显著增加[35]。ALK耐药突变可预测劳拉替尼的高度敏感性,但没有ALK突变的细胞则表现为耐药性。对于未接受过治疗、接受克唑替尼与第二代ALK抑制剂治疗后出现进展的患者,劳拉替尼显示较好的ORR与颅内活性[40]。根据Ⅰ期与Ⅱ期的临床数据,2018年11月劳拉替尼获得FDA加速批准,用于治疗克唑替尼或至少一种其他ALK抑制剂(艾乐替尼或色瑞替尼)后出现进展的患者。劳拉替尼的ORR为48%,4%的患者达完全缓解,中位缓解持续时间为12.5个月。在89名具有可测量颅内病灶的患者中,ORR为60%,完全缓解率为21%,颅内缓解的中位持续时间为19.5个月[40]。一项关于劳拉替尼与克唑替尼对比一线治疗ALK阳性NSCLC患者的Ⅲ期研究正在招募患者(NCT03052608)。许多第三代ALK抑制剂,如恩曲替尼(RXDX-101)和恩沙替尼(X-396)正在试验中,其他新一代ALK抑制剂如贝利扎替尼(TSR-011)、ASP3026、TPX-0005、F17752、CEP-37440、CEP-28122和GSK1838705A也在研发中[41]。预计这些新药将显示出更强的抗ALK活性,可以改善对中枢神经系统病灶的控制,并克服或延迟耐药突变的发展。

ALK抑制剂的应用顺序

治疗携带ALK重排或EGFR突变的晚期NSCLC患者的传统方法是序贯给药,即患者首先接受第一代TKI,出现进展时根据肿瘤分子检测应用第二代TKI和/或化疗[42]。然而,过去几年这一策略受到了临床的挑战。临床证据表明,当第二代EGFR和ALK-TKI用于一线治疗时,患者的PFS、颅内病灶疗效明显提高,且毒副反应明显减轻。

我们中心的序贯治疗经验表明,在ALK重排NSCLC患者对克唑替尼和各种TKI产生耐药后,布加替尼作为二线或后线治疗的疾病控制率为84.8%[43]。其中,15名(42.9%)患者既往仅接受过克唑替尼治疗,而12名(34.3%)既往接受过克唑替尼和色瑞替尼治疗。1名患者仅给予艾乐替尼单药,2名患者给予克唑替尼序贯艾乐替尼治疗,1名患者接受克唑替尼序贯色瑞替尼和艾乐替尼,2名患者接受色瑞替尼序贯艾乐替尼[43]。13名脑转移患者中有7名(53.8%)对布加替尼有反应,所有患者的中位PFS为9.9个月(1~21个月)。在所有其他亚组中(即各种不同治疗组合),除2例既往接受色瑞替尼和艾乐替尼患者出现进展外,所有患者都达部分缓解。

真正困挠的问题是如何对这些治疗进行适当的排序,以便为患者获得最大的临床益处。J-ALEX研究探讨第二代ALK抑制剂用于一线治疗,发现艾乐替尼较克唑替尼具有明显的PFS获益。布加替尼用于二线治疗时,ORR为45%~54%,PFS为9.2~12.9个月[44]。总之,基于耐药突变的后续治疗模式尚缺乏明确推荐,这些模式很难与EGFR耐药突变的后续治疗模式一样,至少在短期内不会被临床广泛应用[43]。

ALK抑制剂与精准治疗

基因组分析和NGS的开展使得以患者为中心的靶向治疗成为可能,称为精准癌症医学[45]。对于NSCLC-ALK阳性患者,深入了解原发性和继发性耐药突变的知识有助于选择最佳的治疗顺序。美国国家癌症研究所(NCI)正在制定一个“主体方案”,根据不同的突变来指导治疗和药物选择,用于ALK重排的晚期NSCLC患者的治疗[46]。这样的方案定义为一个综合操作流程,旨在评估基于特定肿瘤类型、组织学亚型和/或分子标记的队列研究的多个假设[47]。然而,ALK融合蛋白的改变很复杂,包括多种不同的融合伙伴、变构体以及突变等,提示不同的化学敏感性和对抑制剂的抗性机制。在基因指导下的治疗中,药物敏感性与驱动基因改变之间的关系在变化的细胞环境中难以确定。实际上,迄今为止,基于基因组的癌症精准医疗仅于少数有匹配药物的癌症患者中成功应用[48,49]。ALK重排NSCLC的情况是独有的,因为许多耐药性改变是已知的,与其他癌症和各种基因改变相比,还有大量的有效药物可供选择。

在功能精准医学的框架内,个体肿瘤特征与其药物敏感性之间的直接相关性已获证实。具体而言,患者的肿瘤细胞被分离出来并在体外作用于多种合适的药物,以测试其敏感性并结合基因结果用于指导临床。ALK重排的肿瘤治疗后,一旦出现进展即呈现侵袭性生长,大部分患者临床表现为肿瘤浸润胸膜或心包,出现胸腔与心包积液。这些细胞可以通过穿刺收集用于体外分析[50]。在ALK阳性NSCLC患者中,所有的ALK抑制剂可用来进行最有效的序贯选择,以应用于不同的个体肿瘤患者。对于这些患者,没有必要对ALK重排进行重新组织活检或液体活检以选择后续治疗[51]。

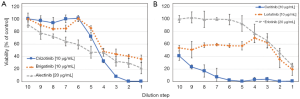

图2所示为ALK-TKI敏感性的测定。肿瘤细胞从胸膜或心包积液中收集并转移到组织培养中。ALK重排的细胞通常组装成空心球体并部分附着在培养瓶上(图2)。图1、图2显示了三个NSCLC细胞系对顺铂和ALK抑制剂的药物敏感性。半数最大抑制浓度(IC50)可从这些剂量反应曲线中计算出来,并与相应的血浆峰值浓度进行比较,以估计肿瘤细胞在临床试验中的敏感性。特别是ALK重排的肿瘤细胞可以用各种相应的TKI进行治疗,从中推断对特定药物的临床反应。此外,体外药敏数据可能与NGS检测的全基因组变化有关。存在的困难是缺乏足够的肿瘤细胞、原发性胸膜肿瘤细胞能否完全代表原发肿瘤以及肿瘤细胞异质性。这些检测正在研发中,还需要在更大的患者队列中进行临床验证。然而,这些检测测试可以在部分患者中短时间内鉴别出最有效的抑制剂,从而可以帮助做出最快的临床决策。

结论

与化疗相比,ALK-TKI显著改善了ALK重排NSCLC患者的预后。ALK抑制剂的应用就是靶向癌症治疗的成功案例。第一个成功的ALK抑制剂克唑替尼正在被第二代药物替代,如艾乐替尼、色瑞替尼和布加替尼,这些药物作为一线药物的疗效也明显提高。最重要的是,新型ALK抑制剂的特点是对脑转移疗效特别好,而脑转移正是这些患者继发性病变的常见部位。尽管半数对治疗无效的患者具有不同于ALK突变的各种耐药机制,第三代药物劳拉替尼可克服大多数患者对所有第一、二代药物的耐药性。遗憾的是,与EGFR继发耐药不同,治疗ALK突变介导的耐药并不简单。关于ALK抑制剂的最佳应用顺序或与其他药物的组合方式,目前尚不清楚。根据ALK重排变异或突变的临床数据,进行选择合适的治疗药物。未来,根据胸膜来源肿瘤细胞体外药物敏感性的功能基因组学结果,可为个体肿瘤患者匹配相应的有效药物提供理论依据。

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. Hohenheim for helpful support.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/pcm.2019.05.03). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;346:92-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pacheco JM, Gao D, Smith D, et al. Natural history and factors associated with overall survival in stage IV ALK rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:691-700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature 2007;448:561-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali R, Arshad J, Palacio S, et al. Brigatinib for ALK-positive metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: design, development and place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther 2019;13:569-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chia PL, Mitchell P, Dobrovic A, et al. Prevalence and natural history of ALK positive non-small-cell lung cancer and the clinical impact of targeted therapy with ALK inhibitors. Clin Epidemiol 2014;6:423-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryser CO, Diebold J, Gautschi O. Treatment of anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small cell lung cancer: update and perspectives. Curr Opin Oncol 2019;31:8-12. [PubMed]

- Palmirotta R, Quaresmini D, Lovero D, et al. ALK gene alterations in cancer: biological aspects and therapeutic implications. Pharmacogenomics 2017;18:277-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosas G, Ruiz R, Araujo JM, et al. ALK rearrangements: Biology, detection and opportunities of therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2019;136:48-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doebele RC, Lu X, Sumey C, et al. Oncogene status predicts patterns of metastatic spread in treatment-naive non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer 2012;118:4502-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang HJ, Lim HJ, Park JS, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics between patients with ALK-positive and EGFR-positive lung adenocarcinoma. Respir Med 2014;108:388-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1693-703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan M, Lin J, Liao G, et al. ALK Inhibitors in the Treatment of ALK Positive NSCLC. Front Oncol 2019;8:557. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rocco D, Battiloro C, Della Gravara L, et al. Safety and Tolerability of Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Inhibitors in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Drug Saf 2019;42:199-209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang R, Pan Y, Li C, et al. The use of quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR for 5' and 3' portions of ALK transcripts to detect ALK rearrangements in lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:4725-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heuckmann JM, Balke-Want H, Malchers F, et al. Differential protein stability and ALK inhibitor sensitivity of EML4-ALK fusion variants. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:4682-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sabari JK, Santini FC, Schram AM, et al. The activity, safety, and evolving role of brigatinib in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancers. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:1983-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel M, Malhotra J, Jabbour SK. Examining EML4-ALK variants in the clinical setting: the next frontier? J Thorac Dis 2018;10:S4104-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christopoulos P, Endris V, Bozorgmehr F, et al. EML4-ALK fusion variant V3 is a high-risk feature conferring accelerated metastatic spread, early treatment failure and worse overall survival in ALK+ non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer 2018;142:2589-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hallberg B, Palmer RH. Mechanistic insight into ALK receptor tyrosine kinase in human cancer biology. Nat Rev Cancer 2013;13:685-700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Du X, Shao Y, Qin HF, et al. ALK-rearrangement in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Thorac Cancer 2018;9:423-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Savic S, Diebold J, Zimmermann AK, et al. Screening for ALK in non-small cell lung carcinomas: 5A4 and D5F3 antibodies perform equally well, but combined use with FISH is recommended. Lung Cancer 2015;89:104-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wynes MW, Sholl LM, Dietel M, et al. An international interpretation study using the ALK IHC antibody D5F3 and a sensitive detection kit demonstrates high concordance between ALK IHC and ALK FISH and between evaluators. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:631-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen HZ, Bonneville R, Roychowdhury S. Implementing precision cancer medicine in the genomic era. Semin Cancer Biol 2019;55:16-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turajlic S, Swanton C. Metastasis as an evolutionary process. Science 2016;352:169. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jonsson VD, Blakely CM, Lin L, et al. Novel computational method for predicting polytherapy switching strategies to overcome tumor heterogeneity and evolution. Sci Rep 2017;7:44206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGranahan N, Swanton C. Clonal heterogeneity and tumor evolution: past, present, and the future. Cell 2017;168:613-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blackhall F, Kim DW, Besse B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and quality of life in PROFILE 1007: a randomized trial of crizotinib compared with chemotherapy in previously treated patients with ALK-positive advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:1625-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2167-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon BJ, Kim DW, Wu YL, et al. Final Overall Survival Analysis from a Study Comparing First-Line Crizotinib Versus Chemotherapy in ALK-Mutation-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2251-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iwama E, Okamoto I, Harada T, et al. Development of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitors and molecular diagnosis in ALK rearrangement-positive lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2014;7:375-85. [PubMed]

- Blackhall F, Ross Camidge D, Shaw AT, et al. Final results of the large-scale multinational trial PROFILE 1005: efficacy and safety of crizotinib in previously treated patients with advanced/metastatic ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open 2017;2:e000219. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spagnuolo A, Maione P, Gridelli C. Evolution in the treatment landscape of non-small cell lung cancer with ALK gene alterations: from the first- to third-generation of ALK inhibitors. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2018;23:231-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katayama R, Friboulet L, Koike S, et al. Two novel ALK mutations mediate acquired resistance to the next-generation ALK inhibitor alectinib. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:5686-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toyokawa G, Seto T. Updated evidence on the mechanisms of resistance to ALK inhibitors and strategies to overcome such resistance: clinical and preclinical data. Oncol Res Treat 2015;38:291-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gainor JF, Dardaei L, Yoda S, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance to First- and Second-Generation ALK Inhibitors in ALK-Rearranged Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 2016;6:1118-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zou HY, Friboulet L, Kodack DP, et al. PF-06463922, an ALK/ROS1 inhibitor, overcomes resistance to first and second generation ALK inhibitors in preclinical models. Cancer Cell 2015;28:70-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin JJ, Riely GJ, Shaw A. Targeting ALK: precision medicine takes on drug resistance. Cancer Discov 2017;7:137-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reckamp K, Lin HM, Huang J, et al. Comparative efficacy of brigatinib versus ceritinib and alectinib in patients with crizotinib-refractory anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Med Res Opin 2019;35:569-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang S, Anjum R, Squillace R, et al. The potent ALK inhibitor brigatinib (AP26113) overcomes mechanisms of resistance to first- and second-generation ALK inhibitors in preclinical models. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:5527-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, et al. Lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology 2018;19:1654-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ziogas DC, Tsiara A, Tsironis G, et al. Treating ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:141. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Recondo G, Facchinetti F, Olaussen KA, et al. Making the first move in EGFR-driven or ALK-driven NSCLC: first-generation or next-generation TKI? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15:694-708. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hochmair M, Weinlinger C, Schwab S, et al. Treatment of ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer with brigatinib as second or later lines: real-world observations from a single institution. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2019; [Epub ahead of print].

- Spencer SA, Riley AC, Matthew A, et al. Brigatinib: Novel ALK Inhibitor for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Ann Pharmacother 2019;53:621-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katayama R, Lovly CM, Shaw AT. Therapeutic targeting of anaplastic lymphoma kinase in lung cancer: a paradigm for precision cancer medicine. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2227-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cecchini M, Rubin EH, Blumenthal GM, et al. Challenges with Novel Clinical Trial Designs: Master Protocols. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:2049-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hirakawa A, Asano J, Sato H, et al. Master protocol trials in oncology: Review and new trial designs. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2018;12:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pauli C, Hopkins BD, Prandi D, et al. Personalized In Vitro and In Vivo Cancer Models to Guide Precision Medicine. Cancer Discov 2017;7:462-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Letai A. Functional precision cancer medicine-moving beyond pure genomics. Nat Med 2017;23:1028-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamilton G, Rath B. Applicability of tumor spheroids for in vitro chemosensitivity assays. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Tian PW, Wang WY, et al. Noninvasive genotyping and monitoring of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearranged non-small cell lung cancer by capture-based next-generation sequencing. Oncotarget 2016;7:65208-17. [PubMed]

丁江华

医学博士,副主任医师,副教授,硕士生导师。现任九江学院附属医院血液肿瘤科副主任。2015年荣获江西省优秀博士学位论文奖。先后承担与参与多项国家、省、市级科研课题。(更新时间:2021/8/15)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Hamilton G, Rath B, Plangger A, Hochmair M. Implementation of functional precision medicine for anaplastic lymphoma kinase-rearranged non-small lung cancer. Precis Cancer Med 2019;2:19.